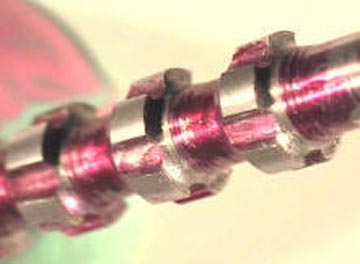

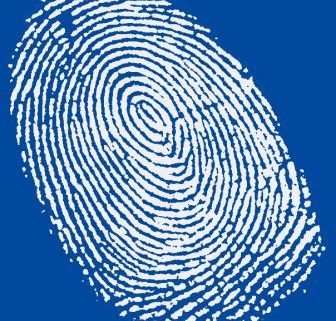

A technique called vacuum metal deposition (VMD) currently uses gold and zinc to recover fingerprints on items such as glass and plastics. VMD is not a new method of of developing latent prints. Not at all. In fact, it’s been around since the 1970’s. However, its latest use has generated quite a bit of buzz among the fingerprint experts and the law enforcement officials charged with locating criminals.

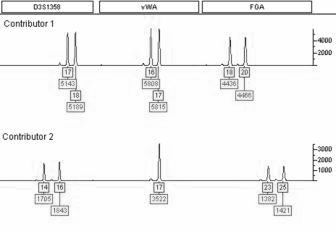

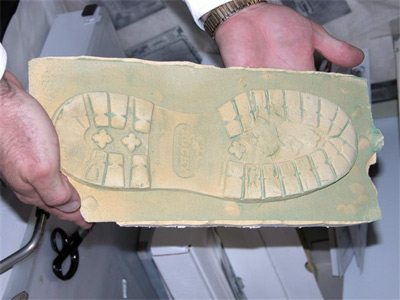

Now, using VMD, experts are finally able to locate and recover fingerprints from fabrics. And the process is relatively simple. The fabric is placed inside a vacuum chamber where gold is heated to the point of evaporation and then the pressure is reduced, which spreads a very thin film over the material. Then, zinc is heated and attaches to the gold, BUT only in the spots where there are NO fingerprint ridges. What’s left behind is clear fingerprint ridges showing through as fabric. The spaces between the ridges show as a grayish zinc color.

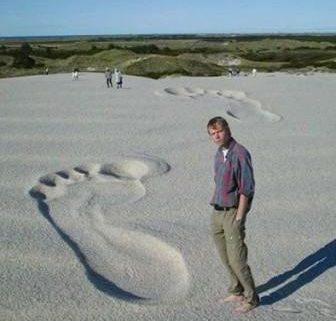

Toronto police lab technician places item in a VMD chamber

Fingerprints recovered using VMD are photographed, not lifted.

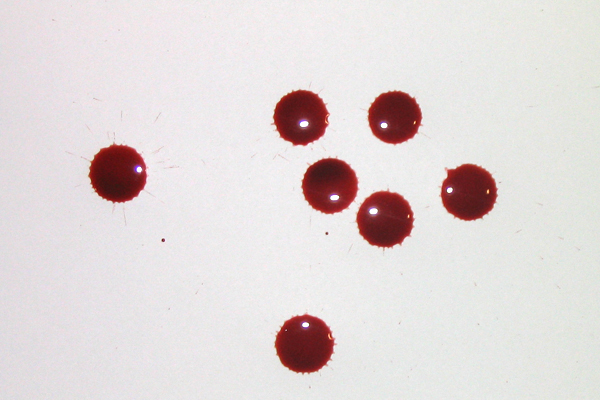

Of course, a fingerprint itself a valuable tool for identification of criminals. But think about how valuable it could be in the case of a victim who police believed jumped to his death from the balcony of a 20-story building. But when scientists run the victim’s clothing through VMD testing, they discover a pair of hand prints on the back of his shirt. Clearly, the presence of those prints would indicate someone had pushed the victim off the balcony. Then, instead of working a suicide case, detectives would then have a murder to solve.

The best types of fabric for turning up positive results are polyester, silk, and nylon.

Another advantage of using VMD is that it can detect prints on items that were previously immersed in water.

background: #bd081c no-repeat scroll 3px 50% / 14px 14px; position: absolute; opacity: 1; z-index: 8675309; display: none; cursor: pointer; top: 276px; left: 20px;”>Save