They have many names and assorted packaging styles. Some are used in one area of the country while others are used elsewhere. They’re often called by their official given names, but many refer to them simply as “rape kits.”

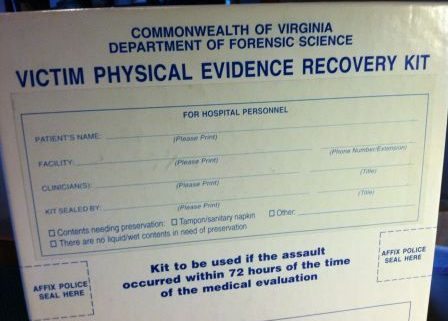

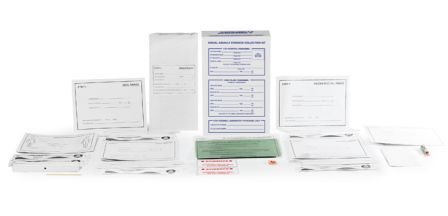

No matter what they’re called, Physical Evidence Recovery Kit (PERK), Sexual Offense Evidence Collection kit ( SOEC), Sexual Assault Victim Evidence kit (SAVE), they’re all designed for one purpose. For the collection of biological evidence in cases of sexual assault and rape.

Typically, when a victim of sexual assault comes to the hospital, an exam is conducted by a specially trained forensic nurse. The victim will also be seen by a physician. First, the medical experts will make sure there are no life-threatening injuries. Then they’ll ask questions about the assault, health history, medications currently taking, etc.

Next comes the actual physical exam conducted by the forensic nurse, including the collection of the victim’s clothing (in the area where I worked the hospital provided new, clean sweat pants and t-shirt if the victim didn’t bring extra clothing), DNA swabs, hair samples, including a combing of pubic hair to collect possible samples left by the attacker. Blood samples are taken, especially if the victim believes she/he may have drugged as part of the assault. A number of hair samples from the victim are also collected.

Victims may refuse any part of the exam, and they may take a break at any time. They may also elect to NOT report the assault to police.

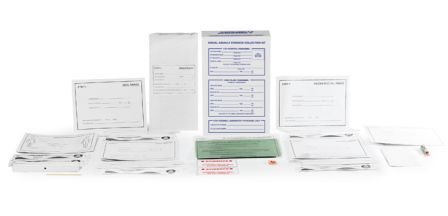

The collected evidence is placed in various pre-packaged containers provided in the evidence collection kits (rape kits). Kits contain items such as swabs, white sheets (placed beneath the victim during the exam), bottles and plastic bags.

In my jurisdiction, the hospital kept a supply of PERK kits in their inventory. The PERK kit is the evidence collection kit authorized by the Commonwealth of Virginia. This is not the case in all states. Please check with authorities in the area where your story is set if you desire to use an actual name as opposed to “rape kit.”

SAVE evidence collection kit – Arrowhead Forensics

SAVE evidence collection kit – Sirchie

FYI – officers DO NOT use the term “rape kit” when around victims of sexual assault and rape. To do so is extremely insensitive, which is why officers in Virginia refer to the kits as PERK kits.

In the meantime, police are busy collecting evidence elsewhere—bedding (sheets, pillowcases), suspect clothing, and the suspect, if identified and located. Sometimes police take an entire mattress as evidence.

Once the forensic nurse completes the exam the evidence recovery kit is sealed and delivered to the lab for processing, which can take many weeks to complete depending upon backlog.

Many writers have asked about the length of time DNA evidence remains viable in sexual assault cases, and where it can be found. Here’s a handy rule of thumb guide. Remember, various circumstances could change or alter these time-frames.

1. Vaginal DNA samples – up to one week.

2. DNA from skin contact – up to two days. If, for some reason, the victim has not bathed it is possible to obtain a suspect’s DNA sample up to a week later.

3. Oral swabbing with positive results – up to two days.

4. Anal – three days.

5. DNA from suspect’s penis – twelve hours after the assault.

6. DNA from fingers in vagina – up to twelve hours.

*By the way, semen can be detected on clothing despite washing. Remember, though, it is possible that DNA can be transferred from one item to another during washing. This is called tertiary transfer.

Those of you who attended Dr. Dan Krane’s presentation at the Writers’ Police Academy may recall when he described how this is possible. In fact, as a world-renowned DNA expert, he’s testified about tertiary DNA transfer in high-profile court cases.

Therefore, writers, it is possible for a DNA sample to show up on the clothing of completely innocent person, such as the unsuspecting roommate who shares a load of laundry with his buddy the psycho- serial rapist. How’s that for a plot twist!

*Thanks to Wally and crew over at crimescenewriter for the topic idea!

background: #bd081c no-repeat scroll 3px 50% / 14px 14px; position: absolute; opacity: 1; z-index: 8675309; display: none; cursor: pointer; top: 620px; left: 20px;”>Save

Amido Black – protein enhancer for blood prints. Click this Link for details.

Amido Black – protein enhancer for blood prints. Click this Link for details.

But it was easier to catch chicken thieves back then than it is to catch modern day bird bandits, the bad guys who poach or kill birds of prey and/or steal their eggs. The eggs, by the way, are most often sold to collectors known as “eggers.”

But it was easier to catch chicken thieves back then than it is to catch modern day bird bandits, the bad guys who poach or kill birds of prey and/or steal their eggs. The eggs, by the way, are most often sold to collectors known as “eggers.”