Before I begin I’d like to point out that REACHER the TV show, like the Jack Reacher books, contains quite a bit of over the top action. There’s a fair amount of fighting and violence. That’s what makes the Reacher legacy what it is. Reacher is an over the top guy who handles his business in an over the top way using over the top tactics and techniques.

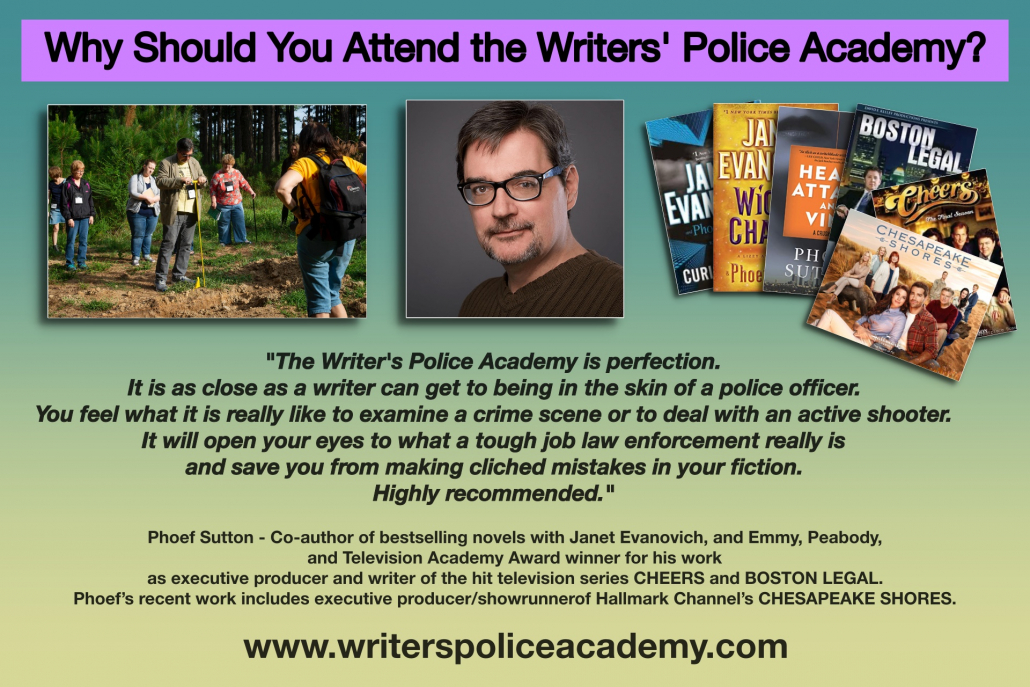

However, the show shows feature live actors portraying law enforcement officers. Obviously, in an over the top depiction of crime and crime scenes, certain liberties must be taken to fit the main character, over the top Jack Reacher. Still, much of what we see and hear regarding the police officers on this show ring fairly true—mannerisms, cop-speak, how they hold weapons, drive a patrol car, handle themselves in deadly situations, etc. So “over the top” aside, let’s take a look at REACHER: Season 1 Episode 2 – “First Dance.”

Off we go …

Part of Reacher’s character is that he sticks up for the little guy. He’s generous with his compassion for those who can’t take care of themselves, which is no surprise knowing Lee Child. Obviously, the author of the novels, who himself has a heart of gold, transferred a piece of that heart to Reacher.

Reacher’s compassion for those whose current position in life is significantly less than fortunate, part of the great layering when building the character, appeared when he encountered a dog who’s abused by its owner. Reacher fills the thirsty dog’s bowl with fresh water and then in true Reacher style let the owner know that he’s taken a keen interest in the dog’s wellbeing.

But that’s just one aspect of Jack Reacher. We continue to learn more about the character as time and dialog and mannerisms pass.

At the conclusion of episode one, we saw Finlay, Roscoe, and Reacher traveling through the countryside, where Reacher said, “Just thinking maybe my brother told me about Blind Blake for a reason. Thinking about him lying in that morgue. Thinking I’m supposed to do something about it.”

“Like what?” said Finlay.

“I guess I’ll find everybody responsible. And kill every last one of them.”

First Dance

Episode two opens in the evening, after dark, with the trio arriving back at the Margrave Police Department. Reacher gets out of the car and storms off on foot heading to the home of Paul Hubble, the likely target of the prison murder attempt. Fortunately for the slim and bookish Hubble, the attackers mistook Reacher as the intended victim. Unfortunately for the attackers, they mistook Reacher as the intended victim. The mistaken identity is confirmed in a later visit to Hubble’s home.

“Where do you think you’re going?, Finlay said to Reacher’s back as he walked away. “Reacher! Reacher, get back here!”

“Maybe give him some space,” Roscoe said.

“I don’t need 250 pounds of frontier justice tearing up this town. Follow him, make sure he doesn’t ruin our case.” said Finlay.

“Why me?”

“Outside the morgue he actually listened to you.”

“And what if he doesn’t now?”

“Shoot him.”

So Roscoe attempts to pursue Reacher, driving her patrol car at the pace of a snail heavily medicated on Valium. The scene is a great example of the mood and setting when working patrol at night.

The world looks different from inside a police car, with the various shades and colors of lights winking and blinking combined with monotone voices spewing softly from the radio speaker.

Looking out from Roscoe’s patrol car as she “followed” Reacher

Working the night shift as a patrol officer is an experience like no other. It’s a side of the city most people never see.

From my article, “WORKING THE GRAVEYARD SHIFT: FERAL DOGS, MANNEQUINS, AND LULA MAE”

“Your headlights wash over the back of an alley as feral dogs and cats scramble out of the dumpster that sits like an old and tired dinosaur behind Lula Mae’s Bakery. The knot of hungry animals scatter loaves of two-day-old bread in their haste to escape the human intruder who dared to meddle with their nocturnal feeding.

A mutt with three legs and matted fur hobbles behind a rusty air conditioning unit, dragging a long, dirty paper bag half-filled with crumbled bagels that spill and leave a trail of stale nuggets in its wake. Tendrils of steam rise slowly from storm drains; ghostly, sinewy figures melting into the black sky. A train whistle moans in the distance.

The night air is damp with fog, dew, and city sweat that reeks of gasoline and sour garbage. Mannequins stare out from tombs of storefront glass, waiting for daylight to take away the flashing neon lights that reflect from their plaster skin.

You park at the rear of the alley, stopping next to a stack of flattened cardboard boxes, their labels reflecting someone’s life for the week—chicken, lettuce, disposable diapers, and cheap wine.

Four more hours. If you could only …”

To read the full article click here.

Roscoe lost sight of Reacher, so she creeps through the neighborhood with ominous horror-movie-esque music playing in the background. She’s glancing to the side, scanning the area for signs of Reacher, when he suddenly appears in front of her car. After jamming the brake pedal to the floor to avoid hitting Reacher who’s standing mere inches from the front bumper, she and Reacher have a discussion. He’s not happy that she’s following him.

Reacher – “I don’t need a babysitter and I don’t need you screwing up my investigation.”

Roscoe – “Okay, first… this is not your investigation. Second, babysitting some giant vagrant is hardly my dream assignment. I could be out there looking for who killed your brother. So stand down and let me do my job, because I’m very good at it. ”

Reacher – “If you were very good at it, you wouldn’t have been trying to follow a man on foot in a police car.”

Roscoe’s argument is valid. Following behind a pedestrian, while driving a marked police car is a goofy thing to do. But I’ve seen supposedly savvy adult law enforcement officers driving along, trying to be discreet, while following suspects who are on foot. They’re either one round short of a full magazine, or they’re lazy. No matter the reason why, it’s not a good tactic.

Totally unrelated, this reminded me of back in the day when I was a field training officer. When I had a brand new officer in the car (many old-timers will back me on this one), if we initiated a traffic stop or saw a wanted person and the subject suddenly ran, well, rest assured I sent the rookie chasing after them, on foot, while I drove like a bat out of hell to the next block, across a vacant lot, a parking lot, etc. to “cut ’em off at the pass.”

Fun Fact -After academy graduation, new officers enter into the second phase of their training, where they receive on the job training under the watchful eye and guidance of a certified Field Training Officer. When they’ve satisfactorily completed the field training program the new officers are ready to hit the streets on their own. The Field Training program was developed in the early 1970s by the San Jose, Ca. Police Department.

After a bit of back and forth, Roscoe convinces Reacher to let her drive him to Hubble’s house.

Once Reacher is seated in the car he turns to Roscoe and said, ” I’m not a vagrant, I’m a hobo.”

Roscoe replied, “Whatever.”

Hubble’s House

- Hubble is not at home so Roscoe and Reacher chat with with wife. The nonchalant fact-seeking banter is good, and realistic.

- Reacher reveals to Hubble’s wife that her husband’s phone number was located in the shoe of Reacher’s deceased brother Joe.

- Reacher notices that one of the Hubbles’ two daughters, like their father, wears glasses. This is the “aha” moment when Reacher realizes that it was Hubble, not he, who was the target of the attack at the prison.

- Reacher asks to use the restroom, an excuse to search for clues, which he finds— a Velcro-like agrimony seed pod, commonly called a hitchhiker, found in the mudroom stuck to a lace in one of Hubble’s dress shoes.

- Hubble’s missing. Reacher believes he’s either on the run or the villain has abducted him.

Roscoe and Reacher visit the scene where Joe Reacher was killed.

Reacher – “Gun had a silencer on it, which makes even close-range work inaccurate, but he got a kill shot.”

The addition of a silencer probably doesn’t affect the accuracy of the pistol; however, the added weight could affect the handling of the weapon—ability to hold it straight and level, etc. Those factors could affect accuracy, unless the shooter is familiar with the silencer-equipment handgun, and has practiced shooting with the suppressor attached.

- Reacher crouched among tall weeds to get a feel for the scene from the position and eyes of Joe Reacher’s killer. This was a great detail. The tactic is one I regularly employed as a police detective. Viewing the scene from the suspect’s position can help spot crucial details you might otherwise miss.

Reacher – “This is where he hid. He enjoyed it. sniper shot from the tree line would have done the job with less risk. The shooter wanted to be close.”

Roscoe – “Maybe it was personal.”

Reacher – “Someone takes your life, it’s always personal.”

Reacher’s statement is one you can take to the bank. Killing another person is extremely personal on many levels. I hope all crime writers incorporate this detail into their work because it can turn an adequate scene and character into something/someone extremely powerful.

The conversation turns to small talk, something Reacher interprets this as Roscoe trying to illicit information to help the department’s investigation into Reacher’s possible involvement in the murders.

Reacher – “Small talk to see if I say something to help your investigation?”

Roscoe – “I’m being nice to a guy who just lost his brother. But, you know, now that you brought it up, you might as well answer my questions.”

So Reacher opened up a bit about his and Joe’s lonely childhood, that Joe was most recently employed by Homeland Security but wasn’t sure which department. Roscoe asked Reacher if he thought Joe’s murder could be linked to his job., but Reacher said they hadn’t spoken for a while so he didn’t know.

Reacher left the scene walking, on his way to find a hotel room.

The hotel parking lot. If fighting is your thing, then here’s a nice one. Quick, too.

Reacher goes into the hotel office where he checks in. On his way out he’s greeted by a group of four young men who’ve consumed a couple of six-packs of beer while waiting for Reacher to arrive. Their mission, assigned to them by the villain of the story, was to inflict bodily harm on Reacher. I’ll pause while you chuckle at the thought of those five unsuspecting men contemplating an outcome of anything short of their own pain and misery.

The cocky leader of the group of thug wannabes said to Reacher – “You’re about to get your ass kicked.”

Reacher replied, “No. I’m just gonna break the hands of three drunk kids.”

Leader – “There’s four of us here.”

Reacher – “One of you has got to drive to the hospital.”

So, the leader of the group took a swing at Reacher and Reacher quickly made good on his promise of breaking the bones of three of the dumb, dumb, dumb men.

The fourth member of the group, the one who still had two good wrists and arms, held his hands in the air and wisely said to Reacher, “Ooh… I-I know where the hospital is.”

Roscoe, who’d been watching from a distance, said to herself, about Reacher, “What the hell just rolled into Margrave?”

A dog without water

The next day, as Reacher walks by the house of the thirsty dog and sees the animal’s bowl is once again empty. So he hops the picket fence and fills it from a hose. The owner steps outside and confronts Reacher who’s squatting beside the dog.

Dog owner – “Can I help you?”

Reacher – “No. Just giving your dog some water.”

Owner – “He must’ve knocked the bowl over, ’cause I gave him water this morning.”

Reacher – “No, you didn’t. Bowl was bone-dry.”

Owner – “You calling me a liar?”

A beat passed and then Reacher said, “Yes.”

Dog owner – “Well, I suggest you leave my property.”

Reacher pats the dog. “Good boy.”

This guy, the irresponsible dog owner, is pushing all the wrong buttons, something he’ll soon regret.

By the way, there is no shortage of cops who love animals who are quick to come to their defense when they’re mistreated. Animal control officers are frequently called by police officers who witness abused and mistreated animals. This often occurs when officers enter homes while serving search warrants or responding to complaints/calls. It is when they’re inside the home or in backyards, places not typically in public view, that such appalling abuse is discovered.

Margrave police chief is brutally murdered.

Margrave police chief Morrison is stripped naked, brutally murdered, and nailed to the wall with six spikes. Part of his male anatomy was severed and subsequently forced down his throat and into his stomach. The chief’s wife is also killed. The medical examiner asks where the body part could/would be located and Reacher replied, “In his stomach. You’ll find them during the autopsy.”

Yes, it would take a bit of strength to hold a man that size a few feet off the floor while hammering spikes through his arms and legs. Reacher easily explained it by saying it took at least four to do that to a guy Morrison’s size.

- The people Hubble worked for said they’d nail him to a wall. Nailing the chief to a wall sent a very clear message to the people within the villain’s organization—screw up and you will find yourself in the chief’s shoes, or lack thereof. Reacher thinks Hubble may already be dead.

- Mayor Teale, as crooked as he is a dead ringer for Colonel Sanders, the king of fried chicken, appoints himself as the new police chief.

Mayor/Chief Teale

- Reacher, Roscoe, and Finlay come to the conclusion they cannot trust anyone in the department outside of their trio. One, if not all Margrave police officers are dirty, as was the chief.

- A man named Kliner practically owns Margrave, from the lovely town square to nearly every major business. It’s his money that allows the town to survive, and it is he who controls the police department.

- Kliner speaks at a town meeting called by Mayor/Chief Teale, a meeting designed to calm the fears of citizens who fear a serial killer, probably Reacher, is loose in their sleepy corporate limits. Kliner tells the people, “I have faith in our police force. I have faith in Chief Detective Finlay. I have faith in our new chief of police, Mayor Teale. And I promise I will provide whatever funds, whatever resources to find whomever is responsible for these heinous acts. You have my word.”

Kilner

- After the meeting, Teale, the newly self-appointed crooked chief of police, sends Finlay on wrong path, steering him away from the murder investigation of Reacher’s brother.

- Finlay to Reacher, speaking of Teale – “Just sent me off to chase my tail.”

- An FBI agent called Picard, a former friend of Finlay, is called to assist. His job is to take Hubble’s family (Hubble is missing) to a safe place and guard them while Finlay, Reacher, and Roscoe sort out the situation. Picard once told Finlay to not take the job in Margrave.

- Reacher takes Hubble’s car and calls Spivey, the prison guard who set up he and Hubble for the prison beat-down, to arrange a meeting. When he arrived he learns Spivey set him up for an ambush, where he’s cut during a knife fight. But, like real life police officers and soldiers, Reacher fights to win and to survive. Losing is not an option. He later told Finlay, while Roscoe closed the knife wounds on his back using Superglue, the two men who attacked him had to be special forces from South America.

Reacher – “Probably military or ex-military—South American.”

Finlay – “How could you know that?”

Reacher – “‘Cause if they weren’t I would’ve killed them within ten seconds.”

Finally – “How’d you know they were South American military?”

Reacher – “Spoke Spanish, had Glock-17s and the technique one guy used to head-butt me was from a martial art hardly anyone uses it except branches of South American special forces. Plus, if they weren’t, I would’ve killed them within ten seconds.”

Roscoe – “Why would South American military be involved in this?”

Reacher – “Don’t know. You ever see anyone like that around Margrave?”

Finlay – “Not till you showed up.”

Reacher – “Then they’re hired muscle. Not running the show.”

Later, and here’s the romance du jour, Roscoe and Reacher head out of town for a bit of R&R and to lay low. They take Roscoe’s pickup truck to a roadhouse across the border in Alabama where the pair have a beer and a belly-rubbing’, gazedeeply-and-longingly-into-your-dance-partner’s-eyes slow dance to Patsy Cline’s classic song, “Crazy.”

Roscoe – “Uh-oh. They’re playin’ Patsy. You know what that means. Means we got to dance. Practically the law.”

Reacher – “I don’t dance.”

Roscoe – “You’re telling me that your mama never taught her sons how to dance?”

Reacher – “She did, but when I ask people to dance, it usually precedes a lot of punching.”

Roscoe – “Good thing I’m doing the asking. Come on …”

It’s a rainy night, a deluge, actually, which leads to a road closure and the pair are forced to spend the night in a hotel room, together. Reacher is shirtless and sleeps on the floor. Roscoe takes the bed wearing only a t-shirt and underwear. But the magic moment was not to be. Not this night.

The next morning Roscoe and Reacher go to Roscoe’s house and find her home burgled and ransacked, complete with muddy footprints on the carpet. Roscoe enters with pistol drawn and Reacher clutching a knife and ready to do battle.

They clear the house, and yes, that is what is sounds like as officers move from room to room making sure no one is hiding. They shout, “Clear! when they’ve determined no one is under a bed, in a closet, behind a shower curtain, or behind a door, etc.

Reacher believes the intruders may have been there to kill him or both of them. As they close the door they discover the words “See you soon” carved on the inside of the wooden door.

“I’m going to need a gun,” Reacher says.

Again, good cop chemistry and mannerisms from the actors, and great writing and adaptation of the books. A lot of violence? Sure. But hey, it’s Jack Reacher, a human bulldozer in a china shop.

Here’s a bit of trivia – Do you recognize this crooner who sent Paula Abdul’s heart aflutter during an early American Idol audition?

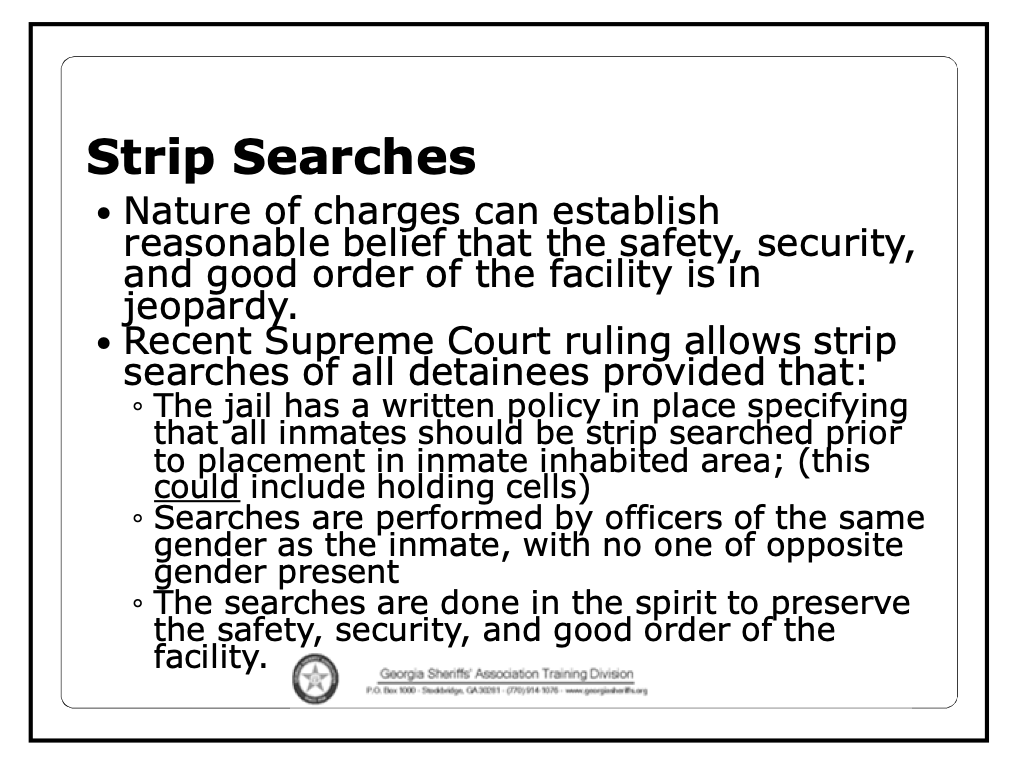

Conklin uses what appears to be an older Crossmatch fingerprinting terminal, or one similar, to record and enter Reacher’s prints into the system. Chief Edward Morrison, played by

Conklin uses what appears to be an older Crossmatch fingerprinting terminal, or one similar, to record and enter Reacher’s prints into the system. Chief Edward Morrison, played by  It was actor

It was actor

By the way, no one knows how or why that family of beavers mysteriously showed up in the the Otter River in Devon, southwest England. They’re doing well, though, and they are the only beavers in England after being hunted to extinction 400 years ago.

By the way, no one knows how or why that family of beavers mysteriously showed up in the the Otter River in Devon, southwest England. They’re doing well, though, and they are the only beavers in England after being hunted to extinction 400 years ago.