A Beaver Tale: How NOT To Leave Fingerprints At Crime Scenes

“Hey, Sarge,” said Officer Trevor “Curly” Barnes. “Would you do me a favor and see if you can get a clear set of prints from this guy? I’ve tried three times and all I get are smudges. I must be out of practice, or something.”

“You rookies are all alike,” said Sergeant Imin Charge. “Always wantin’ somebody to do the dirty work for you.”

“But—”

Sgt. Charge dropped his fat, leaky ballpoint pen on a mound of open file folders. “But nothing,” he said. “All you “boots” want to do is bust up fights and harass the whores.”

The portly “three-striper” pushed his lopsided rolling chair away from his desk and placed a bear-paw-size hand on each knee. Then with a push and a grunt, he stood. The sounds of bone-on-bone poppings and cracklings coming from his arthritic knees were louder than the Buck Owens song—I’ve Got a Tiger by the Tail-–that spewed from the portable radio on his desk.

“Well,” said the sergeant. “Paperwork and processing evidence, including fingerprinting people, comes with the job too. You might as well get it in your head right now that police work is not all about flashy blue lights, driving fast cars, and chasing after badge bunnies.”

“I’m serious, Sarge. I can’t get a good print. I think the guy’s messing with me, or something.”

Charge sighed and rolled his deep-set piggy eyes. Everyone in he department knew the eye roll as Charge’s trademark “I don’t want to, but will” expression.

“All right,” said Charge. “Go finish up the paperwork and I’ll take care of the prints and mugshot. But hurry up and get your ass back down to booking. I get off in thirty minutes and I’ve got plans. There’s a documentary on tonight about how they made the Smoky and the Bandit movies, and I don’t aim to miss it.”

“That’s right, it’s Thursday night, huh?” said Officer Barnes. “What was it last week, The Best of Swamp People?”

“Real funny, you are. No, it was the last part of that series about those beavers that suddenly showed up over in England after being extinct for over 400 years. It was real interesting, it was. Me and Betty Lou never miss those specials. You should check it out. Never hurts to learn something new. Yep, every Thursday nights at 8:00, a pan of peanut butter fudge, and our behinds planted on the sofa. You can set your watch by it. Now, get to working on those reports if you ever want to see day shift again, and you’d better be back here in fifteen minutes to take this slimeball off my hands.”

The sergeant reached over and grabbed the suspect’s right hand, pulling it toward the ten-print card. “Relax, fella’, and let me do the work,” he said while pressing the pad of the man’s index finger onto the ink pad and then rolling it from left to right in the appropriate box on the card.

Twenty minutes later, Sergeant Charge was on the phone with Captain Gruffntuff, the shift commander. “That’s right, Captain. The guy doesn’t have any prints. Not a single ridge or whorl. Nothing.”

A pause while Charge listened. Officer Barnes, back from completing the incident report, leaned toward his boss, trying to hear the other side of the conversation. The sergeant waved him away as if swatting away an annoying fly or mosquito. “No, sir. Not even as much as a pimple.”

Another pause.

“Nope, not on either finger.” Charge leaned back in his chair. “All as smooth as a baby’s bottom. Beats everything I’ve ever seen.”

“Yes, sir. I checked his toes, too. Nothing there either. Slick as a freshly buffed hospital floor.”

Sergeant Charge opened a pouch of Redman and dug out a golfball-size hunk of shredded black tobacco leaves.

“Nope. He’s not from around here. Says he’s from Sweden. Says his whole family’s like that. Not a one of them has any prints. Says it’s a condition called adermatoglyphia. I had him spell it for me.”

Charge shoved the “chew” inside of his mouth, maneuvering it with his tongue until it came to rest between his teeth and cheek.

“Looks like a hamster with a mouth full of sunflower seeds,” Barnes mumbled to himself.

“Yes, sir. Beats everything I’ve ever seen,” Sergeant Charge said into the phone’s mouthpiece. “Will do, sir.

A beat passed, then he said, “Yes, sir. I’ll stay to see it through.”

Another beat.

“Right, sir.”

Sergeant Charge placed the phone receiver back in its cradle without saying goodbye. His typical pinkish cheeks were the color of a shiny new fire truck. He sat silent for a second, thinking.

“Won’t be watching the television tonight, I guess,” he said.

The man from Switzerland, the prisoner, sighed, knowing it was going to be a long night. He’d been through this many times.

“Better call the little woman,” said Sergeant Imin Charge as he reached for the phone to give her the bad news. “And she ain’t going to be happy. No, sir. I’d bet a dollar to a doughnut that she’s already made a dozen or so of those little meatball sandwiches that I like so much. Probably has an ice cold can of Blue Ribbon waiting for me too. And the fudge, well, it’ll have to wait.”

After a few “Sorry, dears,” Charge returned the receiver back to its resting spot and then turned to the prisoner who sat handcuffed to a wooden bench with the back of his head against the mint green wall. Another grease stain added to the collection, thought Charge.

“Okay,” he said to the man who’d been arrested for breaking into home of an Hazel Lucas, an elderly woman who’d whacked the intruder with a rolling pin as he climbed through a kitchen window. “Lemme see those fingers, again.”

The burglar held up his hands and said to the sergeant, “Good luck.”

Photo Credit: Nousbeck et al., The American Journal of Human Genetics (2011)

Adermatoglyphia, or “immigration delay disease” as it’s also known, is an extremely rare and unique condition found in members of only four Swiss families. What’s so unique about the condition? For starters, people with adermatoglyphia produce far less hand sweat than the average person. But, perhaps the most startling characteristic is that people with adermatoglyphia do not have fingerprints.

In one instance, a female member of one of the affected families traveled to the U.S. but was delayed by border agents because they couldn’t confirm her identity. Why? No prints to compare.

The cause of adermatoglyphia has, until recently, been a mystery. Now, however, scientists have learned that the affected members of the Swiss families all had a mutation in the gene called Smarcad1. And this mutation is in a version of the gene that is only expressed in skin.

So yes, for that added twist to your tales, there are people who do not have fingerprints.

By the way, no one knows how or why that family of beavers mysteriously showed up in the the Otter River in Devon, southwest England. They’re doing well, though, and they are the only beavers in England after being hunted to extinction 400 years ago.

By the way, no one knows how or why that family of beavers mysteriously showed up in the the Otter River in Devon, southwest England. They’re doing well, though, and they are the only beavers in England after being hunted to extinction 400 years ago.

The name of the river where they live is a bit ironic since no otters live there.

See, like Sergeant Charge and his wife Betty Lou, some of you learned something new.

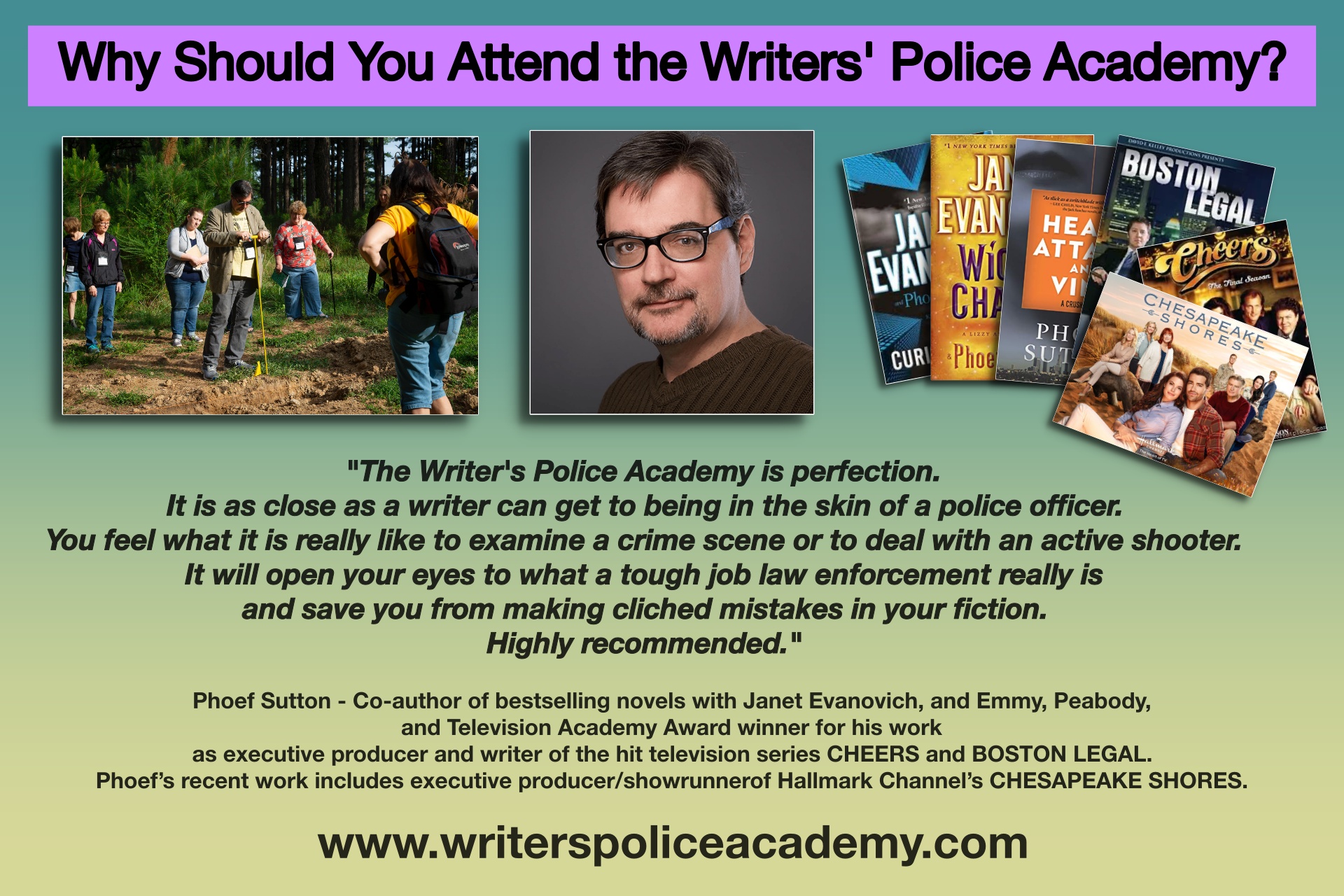

There’s still time to sign up!

If he’s Swiss, he’s probably from Switzerland, not Sweden….

Thanks for catching the typo, Jeff. I’ve corrected it.