Today’s special guest expert is thirty-year police veteran, Lieutenant David Swords (ret.) of the Springfield, Ohio Police Department. Nearly half of Lt. Swords’ police career was spent as an investigator, working on cases ranging from simple vandalisms to armed robberies and murders.

David is the author of a novel, “Shadows on the Soul.” He and his family live near Springfield.

Search Your Heart and Seize the Day

A crime writer’s primer to the Fourth Amemdment – Part 1

How many times have you heard someone complain that a criminal “got off on a technicality?”

Actually, that is a very simplistic way to summarize complex legal maneuverings, but when it does happen, the issue that is probably involved stems from interpretations of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the “Search and Seizure” amendment.

The Fourth Amendment, the heart of search and seizure law, very simply says:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

That’s easy enough to understand, right? Yet, that short amendment has generated more case law than I would care to recount. Entire volumes have been written about search and seizure case law, but I will try to summarize it all using the “K.I.S.S.“ method. That is: Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

The Fourth Amendment says that no agent of the government (including officers at the state and local level) can search anything without a warrant, but … the courts have always recognized certain necessary exceptions to that rule, and it is those exceptions that usually cause problems in court, since the vast majority of searches and seizures are accomplished without officers first obtaining a warrant. I will try to explain many of the more common exceptions to the rule and how they may apply on the street at three o’clock on a Wednesday morning.

However, before we get into the exceptions to the rule, let me explain one issue that is very important. No discussion of searches or arrests would be complete without first defining probable cause, which is really the basis of just about everything a law enforcement officer does. At its simplest definition, probable cause is obtained by the analysis of facts that would “lead a reasonable and prudent person to believe a crime had been committed and that a particular person had committed that crime.” By the way, an arrest is considered a seizure of a person and therefore any claim of innocence can be based on an appeal to the Fourth Amendment.

A seizure of a person is an arrest.

Of course, all of the following exceptions would be moot if an officer always got a warrant signed by a judge, but that can take several hours to acquire and is just not practical in many cases.

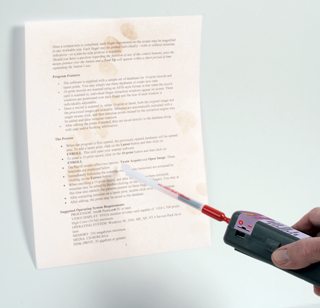

Consent Search

An officer may search anything if the owner gives the officer permission to do so, and there’s no law that says you cannot ask. This seems pretty obvious, but it has been necessary for courts to spell it out when the issue was called into question. Problems can arise with shared property, as in the case of roommates or parent/child situations.

While verbal consent is legal, many departments have forms a person can sign, authorizing an officer to search a car or premises. This precludes the possibility a person could later deny having given an officer consent to search.

Driver gives consent to search his car.

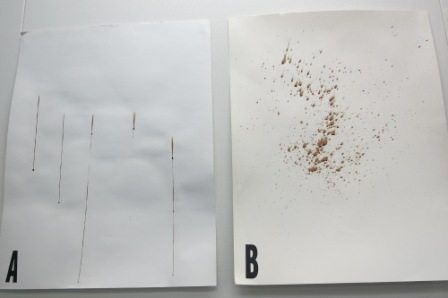

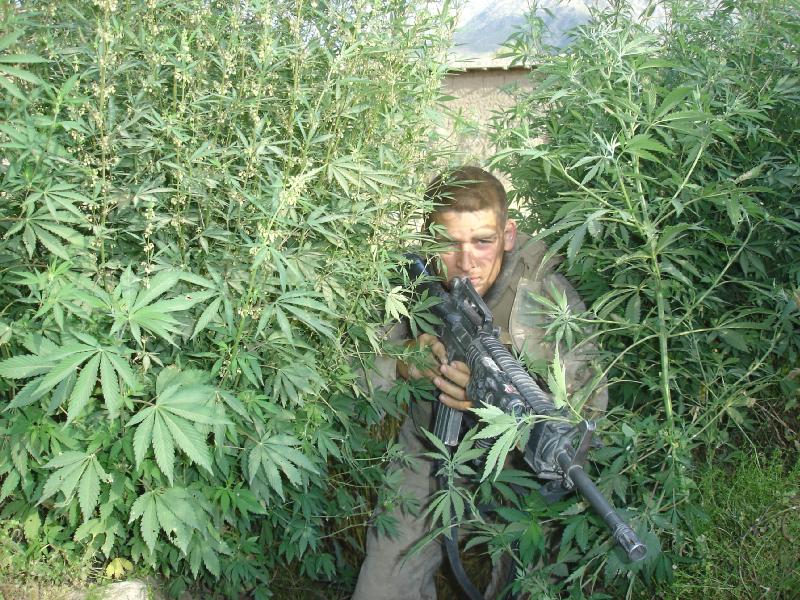

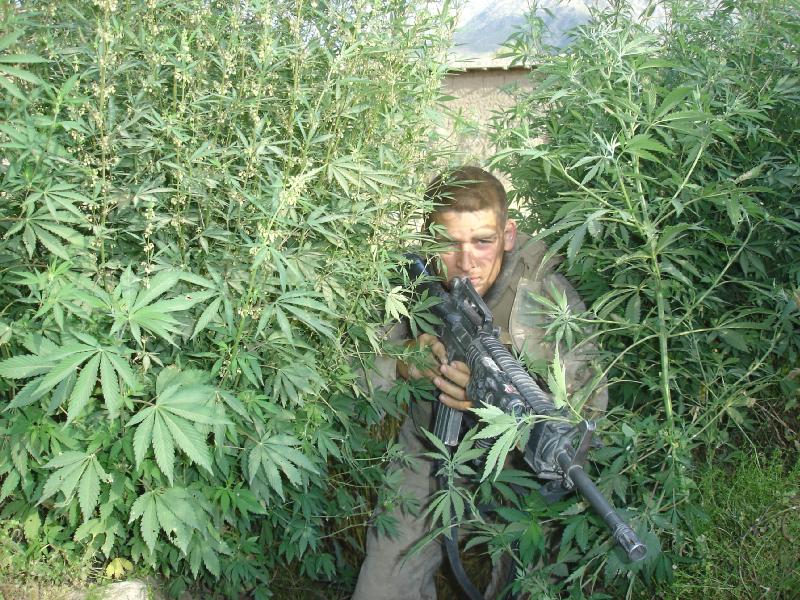

Plain View

Officers may seize any contraband (things that are in and of themselves illegal) or fruits of a crime that they see with the naked eye. The trick here is that they must have a legal right to be where they are when they see the item. Can officers look into someone’s window and then take legal action concerning something they see? If they are on the sidewalk or have been called to the house by the resident and are standing on the front porch, yes they can. But if they have climbed a fence and sneaked into someone’s yard, just because they want to know what that rascal is up to, they may have more of a problem in court.

Marijuana in plain view.

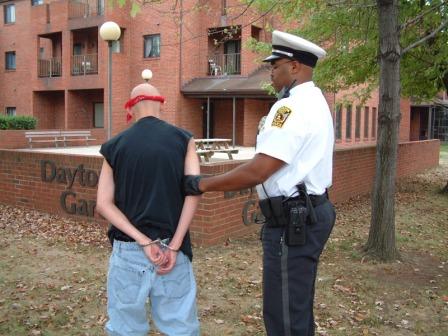

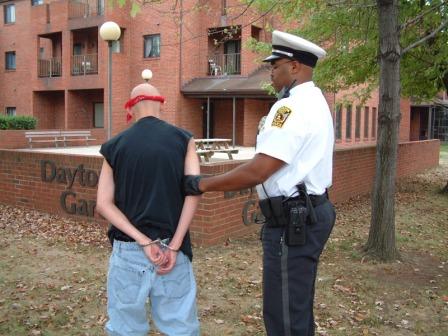

Stop and Frisk or “pat-down” search

This is one instance in which the U.S. Supreme Court decided that officers with reasonable and articulable suspicion (not necessarily probable cause) may stop a person they believe may be involved in criminal activity and conduct a cursory pat-down frisk of the person’s outer clothing to check for weapons. It is not really a search, but a minimal intrusion on a person’s freedom of movement, and conducted primarily for the purpose of safety.

A search incident to a lawful arrest

Officers may search a person they have taken into custody on a legal arrest. Unlike the stop and frisk, this can be a full search of a person’s clothing, purse or even the person themselves. In cases where a person is arrested and then charged with a separate crime because of contraband or evidence found in a search incident to arrest, for instance drugs, and the person is found innocent of the original charge, the evidence seized is usually admissible as long as the arresting officer had good probable cause for the original arrest. Probable cause does not necessarily have to extend to proof of guilt. An officer may have good probable cause and still have an arrestee later found in court to be innocent.

Pat-down (frisk) search for weapons.

This full search capability does not extend to persons stopped for traffic violations, since their detention is temporary and usually not fully custodial. Cont’d…

*Tomorrow – Part two of Search and Seizure with Lt. David Swords