A homicide case is a puzzle, and it’s the job of the investigator to put the pieces together until they see a picture emerge. They may not always complete an entire image, but there should be enough there to clearly know that a crime was indeed committed and that the face that emerged from the puzzle is definitely that of the suspect.

Here are some of the major points/puzzle pieces to consider when investigating a murder.

1. When conducting a homicide investigation always take time to look at the case from the point of view of the defense attorney. What holes are in the case? What does your case lack? What’s missing? What areas could a defense attorney attack? Find those things and then locate the evidence needed to fill the voids. If there’s evidence out there, find it. If it’s not, then know the reason(s) why it’s unavailable. If details are left open-ended, a good defense attorney will use untidy loose ends as a means to indicate their client’s innocence. “If the detective had simply gone one step further they’d have discovered that my client could not be guilty of the crime!” Besides, the things you discover while approaching the case from this angle will almost always help build a better and stronger case.

2. Direct Evidence and Circumstantial Evidence.

A woman is standing at the counter of a dry cleaning store waiting for the clerk to come from the back room. She’s startled by a loud bang. The door to the room opens and a bald man holding a gun in hand runs out and then continues running outside through the open front door. The woman goes into the back room and sees the female clerk lying on the floor. She’s dead from what appears to be a gunshot wound to the head. There is no other entrance or exit from the room. The customer calls the police.

Direct Evidence is something actually observed by the witness, or clear evidence of fact. In the case above the direct evidence is:

a) The sound of the gunshot. The customer actually heard the sound.

b) The customer saw a bald man emerge from the room and he was holding a gun in his hand.

c) The clerk is lying on the floor with what appears to be a gunshot wound to her head. Blood, or what appears to be blood, is on the floor around the head of the victim.

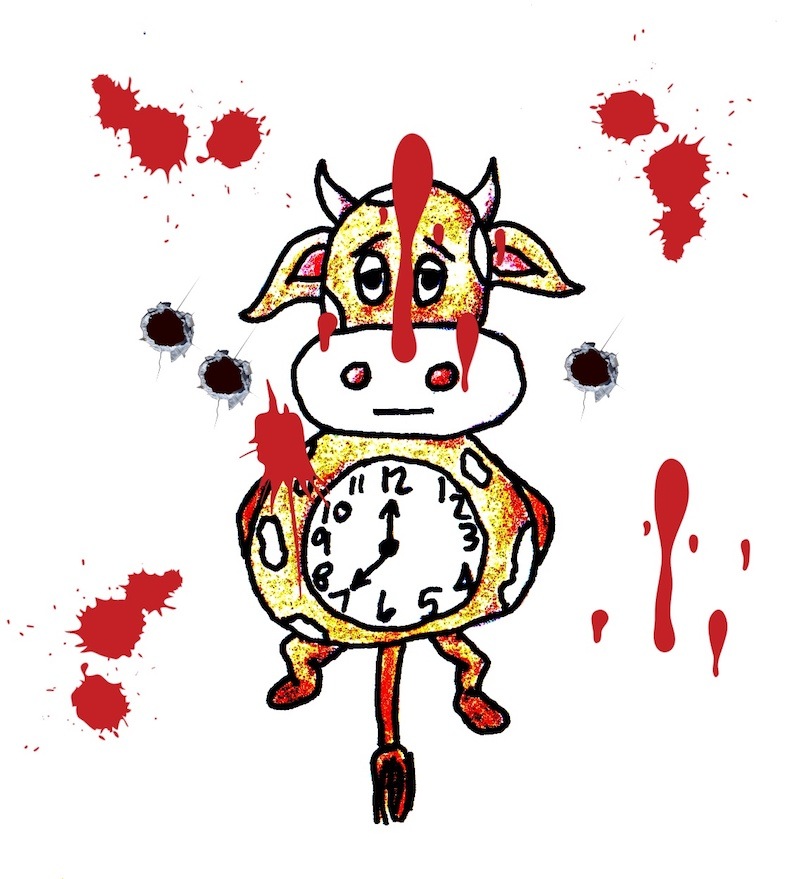

Above image is from the Writers’ Police Academy’s “Treating the Trauma Patient” workshop. It is a staged photo and no one was harmed. The smile on the “victim’s face, however, was very real. She enjoyed teaching writers.

*Officers may not testify that the reddish-brownish liquid substance on the carpet was blood because at the time the material had not been tested and identified by laboratory experts. They may only testify to what they actually know, not what they think.

Circumstantial Evidence relates to fact or a series of facts that infers, but does not implicitly prove, another fact. In the case above we can infer, circumstantially, that the bald man who ran out of the room was indeed the killer because no one else was there, and there was no way anyone could have escaped other than by exiting the front door.

Now let’s revisit the case of the Washed Up Dry Cleaner, but from the defense attorney’s point of view. We, as investigators, know this … The clerk was killed by a gunshot wound to the head. A customer saw a bald man holding a gun run out of the back and then escape out into the street.

The defense attorney is already thinking of angles to defend their client, such as … It’s possible the clerk had tried to kill the bald man who managed to grab the gun, which accidentally discharged during a struggle. Or, the bald man, fearing for his life, fled from the business while still clutching the pistol. Suppose the bald man had witnessed the clerk shoot herself as an attempted suicide, so he panicked, grabbed the gun, and ran to get help? Was there a romantic tie between the two that could’ve resulted in a “heat of the moment” act of violence?

These are puzzle pieces that must be located in order to prove the “maybe this, maybe that” theories wrong, and that the bald man indeed killed the clerk, or not.

3. Proving Fact.

We have the evidence, both direct and circumstantial, so how to we prove the bald man killed the clerk, or that he did not commit the crime? Let’s start by proving the defense theories wrong. Suicide? We’ll check for close contact powder burns and/or stippling, and gunshot residue on the hands of the victim. None there, so suicide is most likely not an option. The same is true for a struggle over the weapon (the self defense claim). No signs of a struggle—defensive wounds, items in the room overturned. Again, no close contact powder burns and/or stippling.

It’s safe to conclude the shooting took place from a distance, not at close range.

Through our investigation, we’ve learned there was no connection between the victim and her killer. Security video shows no one else entered the store other than Bald Man and the witness.

By proving the potential defense theories wrong, we’ve now bolstered our murder case against the bald man.

4. MOM – Motive, Opportunity, and Means

Now that we’ve definitely set our sights on Bald Man as the probable killer, it’s time to dig deep into the box to begin pulling out the puzzle pieces featuring specific details. So let’s call on MOM to help.

M = Motive. At this point, we don’t know the motive so we have to begin a search of the suspect’s personal history (gambling debt, robbery, infidelity, etc.). Detectives will attempt to learn the motive as the investigation progresses.

O = Opportunity. Check. We know that Bald Man was there at the scene of the crime.

M = Means. Check. Bald Man definitely had a gun.

In addition to MOM, there are a few other considerations on our handy checklist, such as:

Intent – Did Bald Man intend to kill the clerk? Ties to motive.

Plan – Did Bald Man plan to kill the clerk? Was this a premeditated act? If so, why? Ties to motive.

Preparation – Did Bald Man take steps to carry out his plan? Did he stockpile ammunition. Did he try to hire someone to commit the murder for him? Get his affairs in order in case he’s caught and goes to jail.

All of these details will be revealed during a thorough investigation.

5. First Responders.

It’s important to alert, train, and beg first responders—patrol officers, EMS, fire, etc. to not muddy up the crime scene by moving, tainting, disrupting, contaminating, or handling evidence.

6. The Crime Scene.

The back room of the dry cleaners is where the shooting took place, therefore it is the primary crime scene, or scene of the crime.

Suppose Bald Man hides the pistol in a dumpster down the street and it’s found by garbage collectors who alert police to their discovery. The dumpster is then a secondary crime scene, or simply a crime scene. Anyplace where evidence of a crime is found is considered to be a crime scene or secondary crime scene. Investigators should label each of those locations appropriately and orderly (Secondary Crime Scene A – dumpster at corner of Main and Killer, Secondary Crime Scene B – top dresser drawer in master bedroom of Bald Man’s residence at 666 Manson Lane, etc.).

7. Sometimes it’s best to work a case in reverse by ruling out potential suspects who couldn’t have committed the crime. Then, when all is said and done, the last man standing, so to speak, is the killer.

So there you have it, a few of the basic steps to solving a murder puzzle.

Finally, click the link for a detailed list of Homicide Investigation Do’s and Don’t’s.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

In case you’re still concerned about the “victim” in the above photo, here she is again enjoying a bite to eat between classes at the Writers’ Police Academy.

The makeup used in these workshops is extremely realistic.

Lisa Black is the NYT bestselling author of 14 suspense novels, including works that have been translated into six languages, optioned for film, and shortlisted for the inaugural Sue Grafton Memorial Award. She is also a certified Crime Scene Analyst and certified Latent Print Examiner.

Lisa Black is the NYT bestselling author of 14 suspense novels, including works that have been translated into six languages, optioned for film, and shortlisted for the inaugural Sue Grafton Memorial Award. She is also a certified Crime Scene Analyst and certified Latent Print Examiner. Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement. Lisa has completed over five-hundred-hours of forensic training that includes basic death investigation, child death investigation, advanced child death investigation, and officer-involved shooting investigations.

Lisa has completed over five-hundred-hours of forensic training that includes basic death investigation, child death investigation, advanced child death investigation, and officer-involved shooting investigations. Tami Hoag is the #1 International bestselling author of more than thirty books published in more than thirty languages worldwide, with more than forty million books in print. Renown for combining thrilling plots with character-driven suspense, crackling dialogue and well-research police procedure, Hoag first hit the New York Times bestseller list in 1996 with NIGHT SINS, and each of her books since has been a bestseller, including her latest, THE BOY. She lives in the greater Los Angeles area.

Tami Hoag is the #1 International bestselling author of more than thirty books published in more than thirty languages worldwide, with more than forty million books in print. Renown for combining thrilling plots with character-driven suspense, crackling dialogue and well-research police procedure, Hoag first hit the New York Times bestseller list in 1996 with NIGHT SINS, and each of her books since has been a bestseller, including her latest, THE BOY. She lives in the greater Los Angeles area.

The material offered at

The material offered at