Allele – The characteristics of a single copy of a specific gene, or of a single copy of a specific place on a chromosome.

Alternate light source – Special lighting device that help investigators locate and visually enhance items of evidence—body fluids, fingerprints, fibers).

Angle of Impact – The angle at which a drop of blood strikes a surface.

Area of Convergence – The area where, when lines are drawn (or through use of string) through the long axes of blood stains, all points intersect. This point of intersection indicates the location of the blood source.

Area of Origin – The location from which blood spatter originated.

Backspatter Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from blood drops that traveled in the opposite direction of the external force applied.

Ballistics – Scientific study of the motion of projectiles.

Biological evidence – Physical evidence that originated from a human, plant, or animal.

Blood Clot – A gelatinous mass formed by a combination of red blood cells, fibrinogen, platelets, and other clotting factors.

Bloodstain – An area where blood contacts a surface.

Bloodstain – An area where blood contacts a surface.

Bloodstain Pattern – A grouping of bloodstains that indicates the manner in which the pattern was distributed.

Bubble Ring – An outline within a bloodstain caused by air in the blood.

Cast-off Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from blood drops released from an object in motion (a bloody hammer or ax, for example).

Chain of custody – The process used to maintain and document the chronological history of the evidence. It is a written record of each person who handled a particular piece of evidence.

Cross-contamination – The unwanted transfer of material between two or more objects. For example, touching an object containing blood and then using the same hand to handle a different item. DNA, blood, etc. could transfer from the original object to the other.

Drip Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from a liquid that dripped onto a surface or into another liquid.

Drip Stain – A bloodstain resulting from a falling drop.

Drip Trail – A bloodstain pattern resulting from the movement of its source.

Edge Characteristic – The physical characteristics of the periphery of a bloodstain.

Electrostatic dust print lifter − A system that applies a high-voltage electrostatic charge on a piece of lifting film, causing dust or residue particles from a print to transfer to the underside of the lifting film.  Some of you may remember seeing this in use at the Writers’ Police Academy. (Picture at right – author Donna Andrews – Writers’ Police Academy)

Some of you may remember seeing this in use at the Writers’ Police Academy. (Picture at right – author Donna Andrews – Writers’ Police Academy)

Expiration Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from blood forced by airflow out of the nose, mouth, or a wound. (Expiration – exhalation of breath).

Firing pin/striker – The component/part of a firearm that contacts the ammunition causing it to fire.

Forward Spatter Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from blood drops that traveled in the same direction as the the item causing the force (A baseball bat in motion).

Homogenization – process of preparing tissue for analysis by grinding tissue in amount of water (precisely measured, of course).

Impact Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from an object striking liquid blood.

Impression evidence – Materials that keep the characteristics of other objects that have been pressed against them, such as a footprint in mud.

Latent print – A print that is not visible under normal lighting.

Latent print – A print that is not visible under normal lighting.

Locard’s Exchange Principle – The theory that every person who enters or leaves an area will deposit or remove physical items from the scene.

Locus – The specific location of a gene on a chromosome; the plural form is loci.

Luminol – A chemical that exhibits chemiluminescence, a blue glow, when mixed with an oxidizing agent. Luminol is used detect trace amounts of blood left at crime scenes as it reacts with iron found in hemoglobin. Horseradish can leave a flash positive, but its glow is not as bright as the glow produced by blood. Other items could also produce false positives, but they, too, do not glow as brightly as blood.

Magazine – A container that feeds cartridges into the chamber of a firearm.

Mist Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from blood reduced to a fine spray as a result of an applied force.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) – DNA located in the mitochondria found in each cell of a body. Can be used to link a common female ancestor.

Nuclear DNA – DNA located in the nucleus of a cell.

Parent Stain – A bloodstain from which a satellite stain originated.

Post-mortem redistribution – Toxicological phenomenon of an increase in drug concentration after death.

Primer – The chemical composition that, when struck by a firing pin, ignites smokeless powder., NOT CORDITE!

Pistol – A handgun which uses a magazine and ejects fired cartridge cases automatically.

Plasma – The clear, yellowish fluid portion of blood.

Plastic − A type of print that is three-dimensional.

Platelet – An irregularly shaped cell-like particle in the blood that is an important part of blood clotting. Platelets are activated when an injury breaches a blood vessel to break. Platelets then change shape and begin adhering to the broken vessel wall and to each other. This is the start of the clotting process.

Pool – An accumulation of liquid blood on a surface.

Bloodstain pattern investigation workshop #2017WPA

Projected Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from liquid blood that’s leaking while under pressure, such as a spurt or spray.

Revolver – A handgun that has a rotating cylinder. Cartridge casings are not automatically ejected when fired.

Saturation Stain – A bloodstain resulting from the accumulation of liquid blood in an absorbent material, such as clothing or bedding.

Serum Stain – The stain resulting from the liquid portion of blood (serum) that separates during coagulation.

Spatter Stain – A bloodstain resulting from a blood drop dispersed through the air due to an external force (a bullet, bat, hammer, rock, etc.).

Spines – A bloodstain feature resembling rays/lines emanating out from the edge of a blood drop.

Splash Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from a volume of liquid blood that falls and or spills onto a surface.

Swipe Pattern – A bloodstain pattern resulting from the transfer of blood from a blood-stained surface onto another surface, such as the swipe/wipe of a rag or cloth through a bloody area.

Transfer Stain – A bloodstain resulting from contact between a bloodstained surface and another area/item.

Crime Scenes … Watch Your Step!

Transient evidence – Evidence that could lose its evidentiary value if not protected, such as blood, semen, fingerprints exposed to the rain.

Void – An absence of blood in an otherwise continuous bloodstain pattern.

Wipe Pattern – An altered bloodstain pattern caused when an object passes through a wet bloodstain.

Bloodstain – An area where blood contacts a surface.

Bloodstain – An area where blood contacts a surface. Some of you may remember seeing this in use at the Writers’ Police Academy. (Picture at right – author Donna Andrews – Writers’ Police Academy)

Some of you may remember seeing this in use at the Writers’ Police Academy. (Picture at right – author Donna Andrews – Writers’ Police Academy) Latent print – A print that is not visible under normal lighting.

Latent print – A print that is not visible under normal lighting.

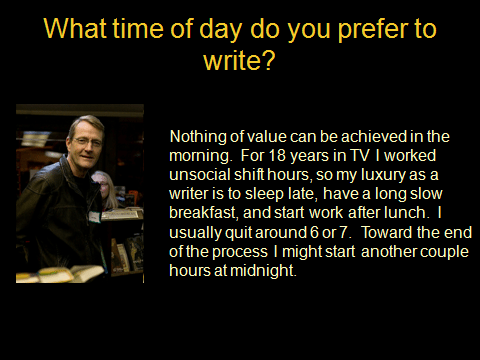

My writer understands the huge differences between the written word and the on-screen action seen on TV and film. Live-action stuff quite often needs over the top excitement to capture and hold the attention of a viewing audience. TV watchers see events unfold in vivid color. They hear the excitement pumping throughout their living rooms via high-dollar surround sound systems.

My writer understands the huge differences between the written word and the on-screen action seen on TV and film. Live-action stuff quite often needs over the top excitement to capture and hold the attention of a viewing audience. TV watchers see events unfold in vivid color. They hear the excitement pumping throughout their living rooms via high-dollar surround sound systems.

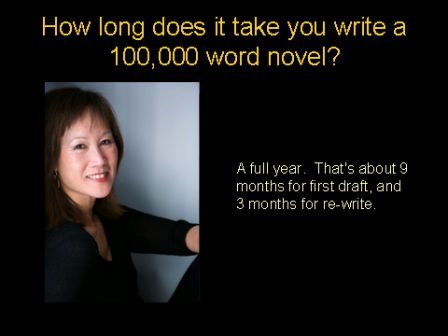

One or two are all that’s needed. Any more and the dialog could become confusing. Besides, too many names eats up word count like watching videos on a crappy wireless data plan chews up precious minutes. The same is true with dialog. A family of twelve all talking to a homicide detective who’s barking out orders to a 10-person CSI team along with four other detectives could wipe out the entire word count in a single, unimportant scene.

One or two are all that’s needed. Any more and the dialog could become confusing. Besides, too many names eats up word count like watching videos on a crappy wireless data plan chews up precious minutes. The same is true with dialog. A family of twelve all talking to a homicide detective who’s barking out orders to a 10-person CSI team along with four other detectives could wipe out the entire word count in a single, unimportant scene. SHOW, SHOW, SHOW!

SHOW, SHOW, SHOW! Edit

Edit