Ask Me Some Questions and I’ll Tell You Some Lies: False Memories

During a police academy class many years ago, an instructor stressed to the group of rookie officers the importance of paying close attention to detail. And, he told them that losing focus on matters at hand could result in overlooking evidence that’s vital to a case. Also important to note, he went on to say, was that not seeing the scene as a whole, including individual people within, such as potential suspects, could mean the difference between the officer living to see another day, or not.

This particular instructor was a firm believer in the use of visual aids, feeling that seeing is believing and that when people experience “hands-on” training they tend to remember those experiences.

Activating the senses by using “hands-on” sessions, such as fingerprinting, traffic stops, crime scene investigation, interview and interrogation, etc., definitely helps to imprint details into one’s memory.

Sure, you could attend the most fantastic lecture about blood spatter and spatter pattens, but the session, not matter how wonderful, would not equal seeing someone use a baseball bat to deliver a blow to someone’s head, an action that sends the red stuff and “matter” spurting and gushing toward a wall or other surface.

Sights, sounds, emotions, and odors associated with an experience sticks in the mind far longer than words spoken by even the best of experts.

For example, the video below from a bloodstain pattern workshop at the Writers’ Police Academy.

One day, the “hands-on” instructor was teaching about eyewitness statements and how reliable they could be, or not, when suddenly a side door opened and in came a line of a dozen people—actors from a college drama class. One held a knife in one hand, another a small handgun, and another carried a notebook. The others were empty-handed. Ten were dressed in typical everyday clothing. Two, a young man and a young woman, were dressed in swim suits. They were both fit. Extremely fit.

The actors walked straight through the front of the room, behind the instructor, and exited through a door on the opposite side of the classroom. The last person through closed the door behind him. The instructor then asked the cadets to write down a description of the people they’d just seen. The results were eye-opening.

Of the entire class only a couple could, with some degree of accuracy, describe four or five of the actors who’d walked past them. A few had a general idea of the peoples’ appearances. But most couldn’t pinpoint exact clothing types and/or hair colors or styles. Shoes? Nope. Gun? No! Knife? No!

But every single male rookie was able to describe, in detail, the woman and the swimsuit she wore. The males in the class were fairly accurate with their descriptions of the man who wore a swimsuit. The two females in the group provided extremely detailed descriptions of the swimsuited man’s arms, legs, and abdominal muscles. Freckles on his back? Check! Biceps? Triple check! They also were equally as accurate regarding the woman’s swimsuit.

The class was astonished at how poorly they’d done with the exercise. Suppose the person with gun had planned to shoot someone? There were many “what-ifs.” Yes, it was a lesson well-learned. Distraction can be a formidable enemy!

Next, during the instructor’s review of what had taken place, he began to question the class members about what they’d witnessed. While doing so he began suggesting things that they could’ve/might’ve seen. Such as one of the actors wearing a Rolex watch (neither actor wore a watch). He spoke about the actor who wore a pair of round eyeglasses (neither of the actors wore glasses of any type). And he discussed with them in detail the tattoo of a bulldog on one of the actor’s forearms. In reality, no tattoos were visible on either of the actors.

This conversation lasted for a several minutes, with the instructor “implanting” those ideas into the minds of the rookie officers. Then the instructor divided the class into smaller groups and then gave them an assignment. Each group was to write a police report that included detailed descriptions of the suspects/witnesses/actors. The results were stunning.

In the last exercise the groups offered far better descriptions of the actors. However, some included the tattoo or the Rolex watch, and/or the round eyeglasses, when in fact those items were absolutely not present.

Some of the rookies unknowingly allowed the instructor to implant the suggestions into their memories. Then, when the groups put their heads together, those who’d “seen” the tattoo, the watch, and/or the glasses, convinced enough of the others so that as a group they incorrectly presented at least one of the items as factual information that was included into their “official report.”

The first exercise was intended to raise officer awareness. They should always pay close attention to everything and everyone in their surrounding area, and as far beyond as possible. And, to not accept as absolute truth everything someone tells them. No two people see everything in the same light, and it’s awfully easy to allow a swimsuit to skew someone’s attention.

The last exercise was to show how easy it is for an officer to sway a witness or suspect’s “memory” during an interrogation. Therefore, law enforcement officers should be aware that their interviews must be based on evidence to avoid planting a false memory.

Remember, if you say something enough times, well, it becomes easy for someone to believe you.

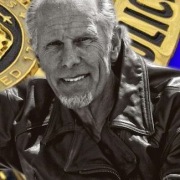

By the way, I was the instructor who led those police academy classes. I was the instructor who led those police academy classes. I was the instructor who led those police academy classes. I was the instructor who led those police academy classes. I was the instructor who led those police academy classes. I was the instructor who led those police academy classes.

Thanks for stopping by.

Lee, this is a very interesting post, and I can confirm from my own experience how true it is. Back in the 80s I worked for a Savings & Loan, and at one point was Assistant Security Officer. My dad had been a cop, and an FBI agent. I also had worked at the FBI (as a stenographer), so I was aware of the importance of description accuracy. I was given the assignment to conduct part of the training classes for new tellers. My hour was to explain (among other things) the procedures they needed to take during a bank robbery. During that portion of the training, the branch manager of the facility where we were having the classes would walk in, interrupting my spiel, and hand me a note. Then she would walk back out of the room. As soon as she left, I would say, “We’ve just been robbed. The person who handed me the note was the perpetrator. Write down as much as you remember about that person’s clothing, and their description.”

It was astounding to everyone that they almost never were able to accurately describe the clothing the woman wore. Some weren’t even aware it was a woman. I explained they would all need to become far more observant of what was happening in their space if they wanted to be a teller who lived through a bank robbery.

Very good. Appreciate the insight.