George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man, died Monday night—Memorial Day—after being handcuffed and held to the ground by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin.

Officer Chauvin, who is white, knelt on Floyd’s neck, apparently using his body weight to press his left knee against Floyd’s flesh. After several minutes Floyd became unresponsive.

The incident continued for an incredible length of time, eight minutes, I believe, with bystanders pleading with the officer to release the hold. They frantically called on other officers to intervene, and when it became clear that Floyd was slipping into unconsciousness they begged officers to check the man’s pulse. One person was heard saying that Floyd’s nose had begun to bleed.

For the entire agonizing event that continued far too long, Floyd repeatedly stated that he could not breathe. He said he was in pain and he even, albeit a weak attempt, called out for his mother. Not one of the officers checked Floyd for signs of life, nor did Officer Chauvin release pressure to Floyd’s neck. And, for reasons unknown to us for now, officers made no attempt to place Floyd inside a patrol vehicle, opting to keep him lying facedown in the street with his hands cuffed behind his back. They could’ve at the very least rolled him over on his side to help him breathe.

Initial reports stated that Floyd had resisted arrest when officers responded to a fraud-in-progress call. However, there was no inkling of any sort of resistance during the time Officer Chauvin held his knee against Floyd’s neck. In fact, Floyd said he’d comply and get inside the car, but was unable to stand to do so. We hear him say this on the video.

Everyone who’s watched the video captured by a bystander has seen a man who “died at the hand of another,” which is the definition of homicide.

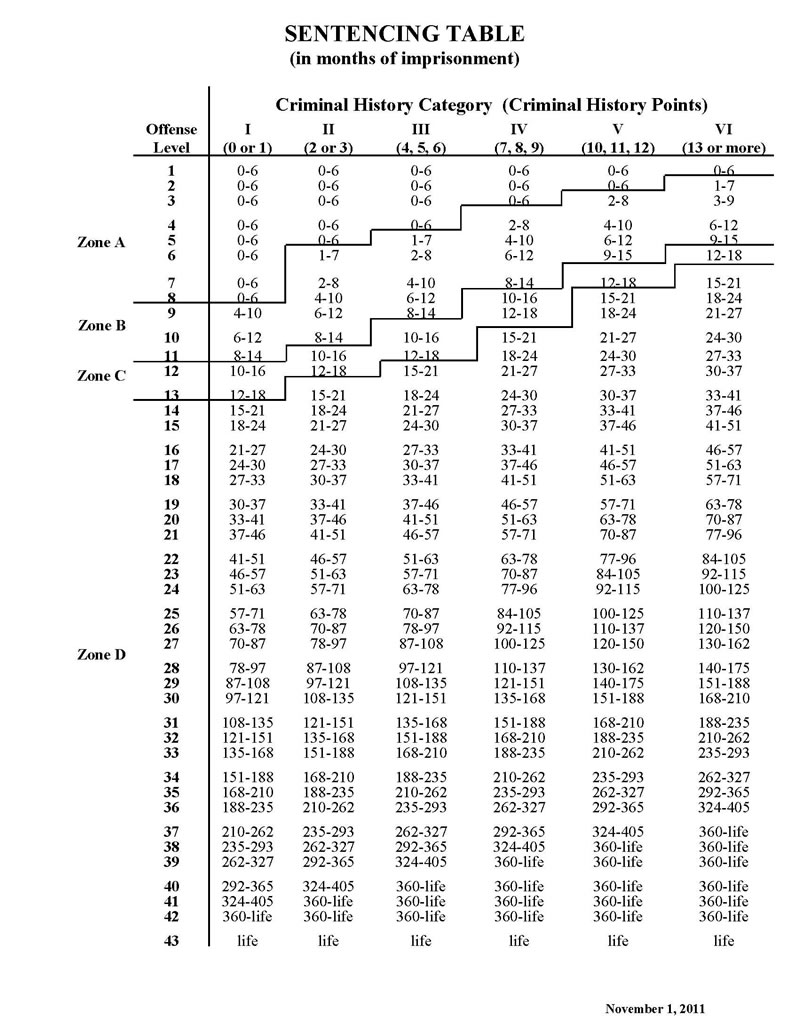

Keep in mind, though, homicide and murder are not always the same, and that difference could be key when this case reaches the court, and it will do to court

Homicide v. Murder.

All, and I repeat, ALL killings of human beings by other humans are homicides. And certain homicides are absolutely legal.

That’s right, L.E.G.A.L., legal.

Yes, each time prison officials pull the switch, inject “the stuff,” or whatever means they use to execute a condemned prisoner, they commit homicide. All people who kill attackers while saving a loved one from harm have committed homicide. And all cops who kill while defending their lives or the lives of others have committed homicide. These instances are not a crime.

It’s when a death is caused illegally—murder or manslaughter—that makes it a criminal offense.

Murder is an illegal homicide.

Here’s the Legal Sticky Wicket

The Minneapolis Police Department’s use of force policy PERMITS chokeholds and neck restraints as long as the officer is properly trained to apply the technique(s). However, their use is not allowed when a subject is complying with commands/not resisting arrest. It’s possible that Officer Chauvin will use department policy as part of his defense. We do not yet know if he’d received this special training. We’ll soon see.

Minneapolis Police Policy Regarding Neck Restraints and Choke Holds

5-311 USE OF NECK RESTRAINTS AND CHOKE HOLDS (10/16/02) (08/17/07) (10/01/10) (04/16/12)

DEFINITIONS I.

Choke Hold: Deadly force option. Defined as applying direct pressure on a person’s trachea or airway (front of the neck), blocking or obstructing the airway (04/16/12)

Neck Restraint: Non-deadly force option. Defined as compressing one or both sides of a person’s neck with an arm or leg, without applying direct pressure to the trachea or airway (front of the neck). Only sworn employees who have received training from the MPD Training Unit are authorized to use neck restraints. The MPD authorizes two types of neck restraints: Conscious Neck Restraint and Unconscious Neck Restraint. (04/16/12)

Conscious Neck Restraint: The subject is placed in a neck restraint with intent to control, and not to render the subject unconscious, by only applying light to moderate pressure. (04/16/12)

Unconscious Neck Restraint: The subject is placed in a neck restraint with the intention of rendering the person unconscious by applying adequate pressure. (04/16/12)

PROCEDURES/REGULATIONS II.

- The Conscious Neck Restraint may be used against a subject who is actively resisting. (04/16/12)

- The Unconscious Neck Restraint shall only be applied in the following circumstances: (04/16/12)

- On a subject who is exhibiting active aggression, or;

- For life saving purposes, or;

- On a subject who is exhibiting active resistance in order to gain control of the subject; and if lesser attempts at control have been or would likely be ineffective.

- Neck restraints shall not be used against subjects who are passively resisting as defined by policy. (04/16/12)

- After Care Guidelines (04/16/12)

- After a neck restraint or choke hold has been used on a subject, sworn MPD employees shall keep them under close observation until they are released to medical or other law enforcement personnel.

- An officer who has used a neck restraint or choke hold shall inform individuals accepting custody of the subject, that the technique was used on the subject.

I wasn’t in Minneapolis when the event occurred, therefore, like everyone else who wasn’t on the scene, I cannot offer an informed opinion, or facts, regarding the events that led to the arrest, placing handcuffs on Floyd’s wrist, or the takedown that resulted in the officer’s knee on Floyd’s neck. However, the video makes clear the events that followed.

Use of Force During an Arrest

When someone uses force to resist an arrest, officers must then use the amount of force necessary to gain control of the person. Normally, this means the officers must use a greater force than that used by the suspect. If not, the combative suspects would always win the battle to run off and continue their criminal activity.

Police officers receive a fair amount of training in the areas of defensive tactics and arrest techniques. They’re taught how to handcuff properly, how to utilize various compliance tactics, and how best to defend themselves against an attack.  The object is always to gain control and cuff the suspect’s hands behind the back, with everyone involved remaining injury free, if possible. Again, though, when a suspect resists arrest officers must do what it takes to bring the situation to a quick resolution. The longer it goes on the more chance of injury.

The object is always to gain control and cuff the suspect’s hands behind the back, with everyone involved remaining injury free, if possible. Again, though, when a suspect resists arrest officers must do what it takes to bring the situation to a quick resolution. The longer it goes on the more chance of injury.

FYI for writers—The ground/sidewalk/pavement/hardwood, etc. provides a sturdy surface that’s used to pin hands, legs, arms, etc. to prevent further movement. Can’t get them to the ground? A wall or car hood also serves the same purpose. Otherwise, the suspect, who’s often much stronger than the arresting officer, could easily fight their way to freedom while severely injuring the smaller officer(s).

Officers Must Use Only the Amount of Force Necessary to Make the Arrest

Before going further, let’s talk about the chokehold and neck restraint. Just so you know, I have quite a bit of experience in this field—I’m a former police academy master defensive tactics instructor and instructor trainer. I’m one of the early members of a defensive tactics federation. I have a strong background in Aikido and Chin-Na. I’m trained in knife- and stick-fighting. I ran my own school. I’ve taught rape prevention and self-defense for women at numerous colleges and at my facility. I’ve trained private security, military, and I’ve trained and taught executive bodyguards.

I’m one of the early members of a defensive tactics federation. I have a strong background in Aikido and Chin-Na. I’m trained in knife- and stick-fighting. I ran my own school. I’ve taught rape prevention and self-defense for women at numerous colleges and at my facility. I’ve trained private security, military, and I’ve trained and taught executive bodyguards.

Chokeholds and Other Neck Restraints

Chokeholds were once taught in police academies across the country. I learned it during basic academy training and later taught the technique at the police academy. Although, we (in Virginia) stopped teaching it many years ago because the tactic could cause death, and did. I’d like to point out that when applied and released properly, the tactic is effective and safe. Still, death had occurred and we stopped teaching it in favor of techniques that are much safer to utilize.

The details of Floyd’s death and the one I mentioned that occurred in Virginia are quite different. Floyd did not appear to be resisting during the time the officer pressed his knee against his neck. The Virginia case, in the mid 1980s, began when someone called the sheriff’s office to report that a relative was acting in a bizarre manner.

A sheriff’s deputy arrived and was instantly attacked. This particular deputy was a huge and very powerful man. And when I say huge I’m talking Incredible Hulk big. I deeply appreciated seeing him arrive when I called for backup. He was a fantastic “equalizer” when we were outnumbered. He and I once arrested a man and then stood back to back to fight our way through a large, angry mob who were hellbent on freeing our prisoner. Yes, I was extremely pleased to have him with me to face that crowd.

Anyway, the subject of the “person acting bizarre” call was a polar opposite of the massive deputy—below average height, and wiry.

To the deputy’s surprise, when the man attacked he immediately went for the officer’s sidearm. The deputy fought to retain the weapon while using his free hand to fight off the violent suspect. Then, in an incredible display of strength, the man ripped the deputy’s leather holster from his gun belt. Yes, he tore the thick leather as easily tearing a sheet of notebook paper.

While battling for control of the man, the deputy managed to grab the firearm (still inside the torn holster) and tossed it onto the roof of a nearby outbuilding. He did so to prevent the man from using it kill anyone.

More deputies arrived to help restrain the very strong and extremely violent man, trying every pain compliance tactic in the book to subdue him.  But nothing seemed to work. He simply didn’t feel pressure applied to his joints and nerves. Even with several grown men trying to restrain him he continued to struggle and resist.

But nothing seemed to work. He simply didn’t feel pressure applied to his joints and nerves. Even with several grown men trying to restrain him he continued to struggle and resist.

After several minutes of fighting and scuffling, a deputy pressed a knee on the side of the man’s neck. His resistance slowly eased and he soon lost consciousness. When he did the deputy immediately released the pressure to his neck. EMS was called and they transported him to the hospital. Unfortunately, he suffered cardiac arrest and died the next day.

Same Tactic Applied, Same Outcome, But Far Different

In the Virginia case, as soon as the deputies felt the suspect stop resisting they quickly reduced the level of force and released the pressure on the man’s neck. They turned him on his side to help him breathe. EMS arrived immediately and began lifesaving procedures.

The Minneapolis officers continued to apply the conscious neck restraint tactic even though Floyd had stopped resisting arrest (at no time during the minutes long video do we see him resisting).

Then, when it was clearly apparent to bystanders, and viewers of the video, that Floyd had lost consciousness, the officer continued using his knee to apply pressure to Floyd’s neck.

At no time did either of the officers attempt to help Floyd breathe, even after he’d lost consciousness. Nor did they check for a pulse.

When EMS arrived, they checked the carotid pulse, walked calmly back to their vehicle where they and others retrieved a gurney. Then officers and EMS workers dragged Floyd’s limp and unresponsive body across the asphalt pavement to the stretcher. Together, they lifted Floyd and placed him on the gurney for transport. When they did Floyd’s head lolled to one side.

There was no sense of urgency.

Again, I wasn’t there so I have only the video as a means to form a slight educated opinion. It will be interesting to hear details as they become available. Since I only report facts, not my opinion, this is all I have to report.

Although, I must say that the video is painful to watch, for several reasons. None of them good.

The Video

Here’s the video of the incident. I caution you that it is graphic. View at your discretion. If seeing someone suffer is not something you care to see, then I urge you to not watch.

A great example are the slang terms Vic (Victim), Wit (Witness), and Perp (Perpetrator). These shortened words are NOT universally spoken by all cops. In fact, I think I’m fairly safe in saying the use of these is not typical across the U.S. Even the slang for carbonated beverages varies from place to place (soda, pop, soda pop, Coke, drink, etc.).

A great example are the slang terms Vic (Victim), Wit (Witness), and Perp (Perpetrator). These shortened words are NOT universally spoken by all cops. In fact, I think I’m fairly safe in saying the use of these is not typical across the U.S. Even the slang for carbonated beverages varies from place to place (soda, pop, soda pop, Coke, drink, etc.). Those of you who’ve written scenes where a cocky FBI agent speeds into town to tell the local chief or sheriff to step aside because she’s taking over the murder case du jour…well, get out the bottle of white-out because it doesn’t happen. The same for those scenes where the FBI agent forces the sheriff out of his office so she can set up shop. No. No. And No. The agent would quickly find herself being escorted back to her guvment vehicle.

Those of you who’ve written scenes where a cocky FBI agent speeds into town to tell the local chief or sheriff to step aside because she’s taking over the murder case du jour…well, get out the bottle of white-out because it doesn’t happen. The same for those scenes where the FBI agent forces the sheriff out of his office so she can set up shop. No. No. And No. The agent would quickly find herself being escorted back to her guvment vehicle.

Keep in mind, things are never the same/uniform across the country. It’s always best, if you’re going for 100% realism, to check with someone in the area where your story is set. The rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

Keep in mind, things are never the same/uniform across the country. It’s always best, if you’re going for 100% realism, to check with someone in the area where your story is set. The rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

Denene Lofland

Denene Lofland