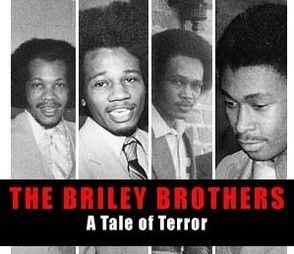

Mecklenburg Correctional Center, a twenty-million dollar institution built in 1977, was once touted as an escape-proof prison. But double fencing topped with miles of looping razor wire, heightened security measures, highly trained staff, and all the electronic bells and whistles, didn’t stop two of the most dangerous killers in America, James and Linwood Briley, from finding a way to beat the system.

How’d they do it? Did they use James Bond-like electronic gadgets to override the security systems? Did they have a cache of high-tech weapons smuggled inside through a network of hidden tunnels? Or, did they have a team of conspirators posing as high-ranking prison officials? Well, believe it or not, all it took for six condemned killers to break free of their death row cell block was a little bit of planning, a few officer’s uniforms, a portable TV, and a fire extinguisher.

The Briley Brothers, along with four other death row inmates, Lem Tuggle, Earl Clanton, Derick Peterson, and Willie Lloyd Turner, began their plan by watching the habits of the guards who worked in the death row section of the prison. A seventh prisoner, Dennis Stockton, was to have joined the escapees, but backed out at the last minute fearing a bloodbath during the jailbreak. However, Stockton helped plan the escape.

During the planning stage, the prisoners quickly learned what size clothing each officer wore, and they managed to learn the secret codes used by officers that locked and unlocked security doors.

After months of studying the guard’s movements, the prisoners decided to make their move. On the night of May, 31, 1984, the inmates overpowered a few guards, took their uniforms, and then set their bizarre plan in motion. They each put on a guard’s uniform and then used the door codes to begin a journey that started from deep inside the prison and ended with the freedom that awaited them outside the gate .

They took a stretcher, placed a portable TV on it, and then covered it with a blanket. Pretending to be corrections officers, they called the officer working the main gate and said they’d found a bomb. They told the gate officer that the situation was dire and they needed to exit the prison immediately to dispose of the device.

The Brileys and their partners in crime knew the prison had never dealt with a bomb before and figured there was no set procedure for dealing with one. Their assumptions were correct.

The six inmates made their way to the front gate, carrying the faux bomb. One of the prisoners occasionally sprayed the “bomb” with the fire extinguisher, hoping to make the situation seem more realistic. The men placed the device into a prison van and climbed inside. The officer working the controls opened the gate and allowed six death row inmates to drive off into the dark Virginia night. It would be a little over an hour before prison officials realized they’d been hoodwinked.

I remember receiving the call about the Brileys’ escape. It was an odd feeling to learn that some of Virginia’s most notorious murderers were on the run. I also remember wondering how they managed to pull off such a daring move. My first thought was that they’d most certainly killed several people in order to successfully reach the outside. It’s mind-boggling, to those of us in the business, when we hear of any prison escape. But an escape from a death row? Impossible, or so I thought. To understand why I say impossible, you must know a little about a maximum security facility.

Large prisons, such as Mecklenburg Correctional Center, are like small fortresses that contain several smaller fortresses inside the sprawling compounds To reach either of these smaller sections of the prison, you must first pass through several locked gates, doors, checkpoints, housing units, medical facilities, security stations, electronically controlled doors and gates, and you’ll most certainly pass dozens of employees before reaching the exit gate.

The exit is not a simple gate like you’d find in a nstandard chain-link fence. A prison exit is actually two separate gates with a large space between the two called a sally port. The person exiting the prison must approach the gate and press a call button. A guard in a tower is responsible for the electronic gate controls (the purpose of the tower is so that no one can get to the officer and force him to open the gates). Still, there are guards on the ground who visually check to see who is coming and going.

When the ground and tower officers are certain the person at the gate is someone who’s allowed to leave (they should confirm by ID card and facial recognition), the tower officer opens the first gate. The person exiting the prison steps, or drives (there are separate, smaller sally ports for pedestrians), inside the sally port and waits for the gate to lock behind him. Then the officer opens the second gate, which is the final barrier to the outside. There are numerous checks and balances in place to prevent escapes. On the night of the Briley escape, every single check and balance failed. The cause—human error.

The events of May 31, 1984, are best described by Richmond Times Dispatch reporter Bill McKelway. Mr. McKelway writes:

* The following is an excerpt from a Richmond Times Dispatch article written by Bill McKelway

May 31, 1984, was a Thursday, a beautiful spring day.

Richmond Times Dispatch image

Nearly a dozen of the 24 death-row inmates knew of an escape plan. All but six backed out. The plan depended on a domino effect of good fortune.

Guards didn’t notice that an unusual number of death-row inmates suddenly appeared clean-shaven with their hair neatly kept that day. If they had, perhaps the change would have signaled to them that it was “E-Day” — escape day. How could the rough-looking inmates pass for guards if they looked like slobs?

At 6 p.m. in the recreation yard, inmate Lem D. Tuggle Jr. walked over to Stockton with a question.

“We’re gonna leave tonight and I need to know how to get away from here. Can you tell me which roads run into North Carolina and where they are?”

The words were recorded by Stockton in his diary.

Stockton, a moonshine-running country boy, had backed out of the escape; Tuggle figured he would have to drive the getaway vehicle himself.

“I wish you were going,” Tuggle is said to have told Stockton, the only other white man among the group of likely escapees. “I’ll stick out like a bad penny.”

About 8 p.m., the bulk of the prisoners left the yard and waited in a bunch to enter death row’s C pod.

Lagging behind, inmate Earl Clanton Jr. darted into the bathroom adjoining the control booth. The door was unlocked, and no one saw him.

The others quickly dispersed into the pod; guards failed to count them or notice that Clanton was missing.

A nurse arrived to administer medicines, only to find a locked bathroom, where she would usually draw water for the pills. James Briley concocted an explanation off the top of his head, according to Stockton. Earlier in the day, someone had said the bathroom was out of order, Briley told the guards. They believed him, and the nurse went elsewhere.

About 9 p.m., James Briley asked the guard in the control booth for a book from the adjoining day room.

The guard opened the door to the booth, Briley yelled to Clanton, and Clanton burst from the bathroom into the booth, subdued the guard and used the control panel to open all the cells.

Within three minutes, the inmates took control of the pod. Unarmed guards were stripped of their clothes, their mouths were taped shut, their hands tied behind their backs.

Uniforms were piled on the floor, and the inmates searched through them for pants and shirts that fit.

Guards arrived one after another, wondering why there seemed to be delays or that they hadn’t heard back from co-workers. Each was seized by uniform-wearing prisoners. The hostages were kept in cells. Some inmates protected guards and nurses from attack.

When a white-shirted lieutenant was captured, he complied with orders that he summon a van.

“We have a situation here,” he barked, a knife at his throat.

Informed that the inmates had a bomb, a guard brought up a van, making sure to use an older vehicle so an explosion wouldn’t damage a new vehicle.

“So you had this man willing to spare a new van but not seeing anything wrong with six men he thought were officers possibly getting blown up,” said Lettner, author of the state police report.

The inmates found a closetful of riot gear. They donned helmets and armed themselves with shields. Gas masks dangled around their necks.

They were in absolute control of C pod, even as walled-off inmates and guards in the rest of the building remained oblivious to what was transpiring.

The escape route from Building 1 was still blocked by a guard in the main control room at the front door. She was lured away with a fake report that she had an outside call.

The lieutenant, still threatened, told her over the phone that a replacement would be showing up so she could leave her post to handle the call.

The guard opened the door to the entryway control booth as she saw her replacement approaching, a man she didn’t recognize.

It was inmate Derick L. Peterson. He subdued the guard and called upstairs to James Briley, who yelled out to the other inmates: “He’s in!”

Peterson could hear cheers over the phone.

The van arrived at the sally port inside the prison’s main vehicular entrance. The sally port is a double-doored, cagelike structure designed to isolate vehicles within the two gates so that a vehicle’s contents can be checked and the identity of any personnel entering or leaving the prison can be confirmed.

A vehicle enters through one of the gates; the gate closes; the vehicle is then confined and checked. The second gate opens and the vehicle leaves.

What came next was one of the most bizarre sights to ever emerge inside the walls of a prison.

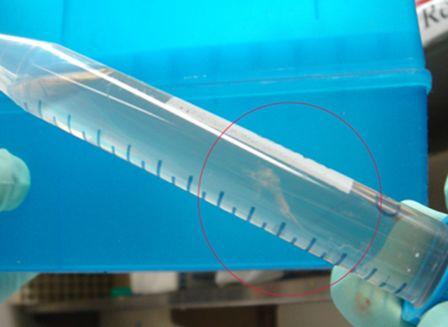

Six death-row inmates, each one a heartless killer dressed in riot gear, burst through the door of Building 1 with a wheeled stretcher. They yelled they had a bomb; two of the men were hosing it off with a fire extinguisher, supposedly to cool the explosive.

The bomb, under a blanket, was the television set from death row.

The inmates, their identities obscured in the darkness and beneath helmets, hustled toward the van across the prison yard. They loaded the bomb into the van and told a guard to open both gate doors at once.

She briefly objected, saying it was a blatant violation of policy.

But she relented, opened both gates, and the van passed into the pitch black countryside.

The two Briley brothers, Clanton, Peterson, Tuggle and Richmonder Willie Leroy Jones were free.

There had been no bloodshed, no gunfire. A prison van loaded with a TV set and six murderers rolled toward North Carolina. They had $758 in cash taken from guards, plenty of clothes and hundreds of marijuana cigarettes.

It was 10:47 p.m.

Harold Catron, the prison security chief, still remembers the late-night phone call that awakened him.

“They told me death-row inmates had escaped,” Catron recalled.

He responded with an expletive.

Catron’s world suddenly turned upside down.

“My God, I’m going to lose my job,” he thought.

Then his mind tried to absorb the mayhem that might follow.

“I thought of the murders that would happen, the rapes that could follow, as they tried to get away.”

Snook, the lawyer, turned to his wife in bed. The radio was blaring news of the escape.

“I tried to tell them,” he said. “What happened?”

~

The news spread slowly.

Investigations of the escape revealed that precious chunks of time elapsed before area law-enforcement agencies, as well as the state police, were notified of what happened.

Even the on-site prison command didn’t learn until 11:15 p.m., Lettner said.

State police were told at 11:31 p.m. — not by the prison but by the Mecklenburg County sheriff’s office.

In the nearby town of South Hill, the acting police chief said descriptions of the escapees didn’t reach him until Friday afternoon, 16 hours after the breakout. Initial reports from the prison said there were five escapees, not six. Prison officials did not offer a formal explanation.

At the Executive Mansion, Gov. Charles S. Robb had just dozed off to sleep when the phone rang.

“It was 1:30 or 2 a.m. in the morning and I can remember being pretty upset that all this time had apparently gone by before the word went up the chain of command or whatever and got to me,” Robb said last week.

“I particularly remember feeling concern for the inmates who had helped keep harm from coming to the guards.”

As the enormity of the escape began to sink in, memories awakened about the Brileys’ victims, the viciousness of the crimes and the random nature of what had befallen the Richmond area in 1979.

Suddenly, Richmond seemed a city about to come under siege by some terrible, too-familiar force: the Briley brothers.

“I think what concerned me the most was that I had seen firsthand what they were capable of doing. I knew their determination to seek revenge. You never forget the smell of death and the smell of blood from what they did,” former Richmond detective Woody, now city sheriff, said this month.

So Woody made sure he was armed at all times. He drove different routes to and from work and around town, and he moved his family to a safe location.

Judges, witnesses, prosecutors and victims’ relatives were given protection. Even the family of Meekins, whose testimony sent the brothers to prison, was warned to take precautions.

Gallows humor surfaced as well. A set of playing cards with cartoonlike images of the escape and capture would later appear in Richmond.

Neighbors of Warren Von Schuch, who had helped prosecute the Brileys and is now Chesterfield County special prosecutor, fashioned a posterboard-sized sign for the Brileys, pointing them to Von Schuch’s house across the street.

“Actually, I’d moved out of the neighborhood by then,” said Von Schuch, who had started packing heat.

Two of the escapees, Peterson and Clanton, were captured that Friday morning just across the North Carolina border, sipping wine from a bottle inside a coin laundry. Their prison-issue shoes gave them away.

The arrests and discovery of the escape van in the area fueled the notion that the Brileys and others remained near Warrenton, N.C. More than 200 law-enforcement agents in Virginia and North Carolina, along with scores of media representatives, converged on the community, now transformed from a sleepy town to a place where residents waved guns instead of hello.

Warrenton was sealed off by police.

Some residents patrolled their property with weapons at the ready.

“I’m going to blow the man’s head off and then ask questions,” Frank Talley, a shotgun on his lap, told a reporter.

Alleged sightings popped up across Virginia and North Carolina, from Portsmouth in the east to Rowan County, N.C., 120 miles to the west.

Missing underwear on a clothesline near Warrenton sparked fears of a Briley in the area, attracting dozens of officers.

Key investigators interviewed recently, however, revealed that Virginia State Police had reliable information that the four remaining escapees — the Brileys, Tuggle and Jones — had traveled north and passed Richmond before dawn Friday, June 1.

The startling information was kept highly classified. V. Stuart Cook, then head of Richmond’s major-crimes unit, doesn’t recall being told.

But the information focused a key, clandestine element of the investigation northward even as swarms of police and the media chased reports of sightings to the south for more than two weeks.

A blue pickup truck stolen near Warrenton overnight May 31 was the key.

In interviewing the owner, former state police criminal investigator Larry Mitchell said, state police determined the likely range of the vehicle before it would need refueling.

Agents focused on one of the few all-night gas stations along the Interstate 95 corridor north of Richmond.

“It turned out that there was a sighting at a station in Thornburg” about 50 minutes north of Richmond, Mitchell said. The description of the vehicle matched and so did the arrangement of its four occupants: three black men and a white man.

“The white guy was in the bed of the truck facing backwards,” Mitchell said.

Years later, Tuggle would tell reporters he had trouble tracking the escape route because “they made me sit in the back; all I could see was the back of the highway signs.”

Tuggle, minutes after robbing a store clerk at knifepoint, would be arrested June 8 in Vermont’s southwest corner trying to outrace a local constable.

Tuggle was driving the truck stolen in Warrenton.

“He popped like a grape,” said a state trooper when asked the day of the arrest if Tuggle was cooperative.

Tuggle said the Brileys exited the truck in Philadelphia, Mitchell and Lettner recalled.

Tuggle watched the Briley brothers ditch part of their correctional uniforms and a badge in the hollow of a tree in a park in Philadelphia, Mitchell said.

That same day, June 8, police arrested Jones in northern Vermont a few miles from the Canadian border, leaving only the Brileys unaccounted for.

Jones, whose mother persuaded him to surrender, had been driven north by Tuggle.

Back in Philadelphia, state police agents working with the FBI found the uniforms hidden in the tree. The hunt for the Brileys in the City of Brotherly Love heated up.

A key focus was an uncle, Johnnie Lee Council, who lived there.

But Mitchell said agents found it very difficult to track the man’s movement because of the teeming North Philadelphia neighborhoods he frequented and the traffic congestion.

A big break came with a call to a person in New York whose telephone was being monitored. Lettner and Mitchell declined to discuss specifics of the call.

But immediately after the escape, efforts were put in place to monitor Briley relatives, former associates and people they had been in contact with throughout their prison years.

It took two days to locate the origin of the call to New York: a garage in North Philadelphia. The FBI sent an informant to see who was there, Mitchell said.

Descriptions came back fitting the Brileys.

Within a matter of hours that day, June 19, teams of federal agents swarmed the building, catching the Brileys barbecuing chicken over a charcoal fire in an alley.

They had been sleeping in the garage, doing odd jobs and befriending neighbors.

People called them Lucky and Slim. Linwood was Lucky; James was Slim.

Fairmont in North Philadelphia, where the capture went down shortly after 9 p.m., was a no-questions-asked neighborhood notorious for crime and secrecy.

“It’s where people live to prey on other people,” taxi driver Richard Batchlor told a reporter at the time. “You live here, you get preyed on.”

“All I could see was barrels of shotguns,” said Dan Latham, who owned the garage, when police stormed the place. He had no idea, he said, who Slim and Lucky really were, even as the three of them listened to news reports of the escape.

Charges of aiding and abetting against Council, the uncle who helped settle the Brileys in Philadelphia, were dropped.

Within minutes of the capture, Jay Cochran, head of the state police’s Bureau of Criminal Investigation, called the trooper on duty at the Executive Mansion.

When Robb got on the line, Cochran uttered the words that ended 19 days of torment: The Brileys were in custody. No one had been harmed.

~

The Briley brothers returned to Richmond on June 21, arriving at the now-demolished State Penitentiary — located near the NewMarket Corp. (formerly Ethyl Corp.) complex off Belvidere Street — about 9:15 p.m.

Driven from Philadelphia by a cortege of law-enforcement vehicles, the two brothers received a loud reception from the 900 inmates who quickly became aware of their presence.

“I don’t know if it was cheers or jeers,” a supervisor with the U.S. Marshals Service said at the time.

Death by electrocution would soon follow, the end game in a years-long legal process rather than retribution for escaping.

Linwood, 30, went first. His case had been heard by about 40 judges since his arrest in October 1979. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected his final appeal Oct. 11, 1984; he died the next night at 11:05 for the murder of disc jockey John “Johnny G” Gallaher.

Prison officials at the State Penitentiary rejected Briley’s request that his last meal be the same as that of other inmates. He received steak instead of fried chicken.

He was able to hold his mother in his arms earlier in the day, but the same opportunity was not extended to him regarding his son, then 10, a child who went on to become a career criminal.

Hundreds of protesters chanted or wept on either side of Belvidere Street as the death hour approached: one side spelling out “F-R-Y,” the other holding candles.

Cook, of Richmond’s major-crimes unit, witnessed the electrocution, calling it “quick and uneventful.”

Death-row inmates at Mecklenburg signed a petition, saying they would protest the execution by not eating. Eleven of the 19 signers ate anyway.

Linwood Briley’s execution was the second in Virginia after the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. The total is now 102.

James Briley was executed April 18, 1985, also in the electric chair at the state prison in Richmond.

In a last interview, he professed his innocence and his love for his brother, whose death steeled his courage.

James said he had vowed to be nearby at his brother’s execution, something prison officials didn’t want. James said he took two hits from a stun gun and was dragged away.

“I told them I wouldn’t leave my brother. I wouldn’t walk out.”

The morning of James’ execution, fellow inmates rioted in hopes of stalling the electrocution. They injured nine guards in brutal attacks that used homemade knives. In the minutes before he died, James twice looked to witnesses and asked, “Are you happy?”

Tuggle, the last of the escapees executed, chose lethal injection. He died Dec. 12, 1996. A tattoo on his arm spoke to a bitter truth: “Born to Die.”

Tuggle was almost buoyant in his last words to witnesses. He entered the death chamber and shouted, “Merry Christmas.”