When You DON’T Have The Right To Remain Silent

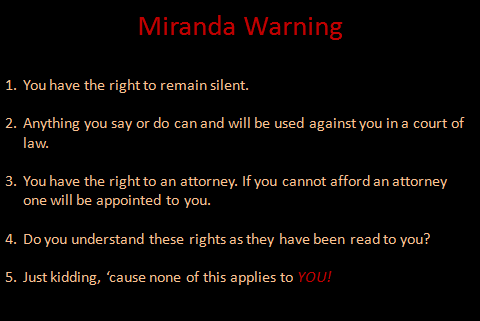

The premise is simple. Whenever a criminal suspect is in custody, and prior to interrogation (questioning), he must be warned of his rights as set by Miranda.

In addition, police may question the suspect(s) only after the person in custody acknowledges that they understand those rights and voluntarily waive them. However, suspects may choose to invoke their rights—remain silent, request to speak to an attorney, etc.—at any point during the questioning, at which time the police must terminate the interrogation.

The consequence for police not adhering to Miranda is great. Basically, no Miranda warnings = statements made by the suspect may not be used in court. Therefore, a confession to the crime(s) is totally worthless.

The U.S. Supreme Court, however, has ruled that there is one (only one) exception to Miranda—the Public Safety Exception.

The Public Safety Exception to Miranda is simply this…law enforcement may ask limited and extremely focused questions without warning the suspect of his rights according to Miranda, and the answers to those questions may be introduced in court proceedings. Under this exception questions must be limited to facts relating to a specific and immediate threat to the safety of the public.

Invoking the Public Safety Exception does not mean that authorities have free reign to question a suspect about any and everything under the sun, including questions relating to the crime for which the suspect is currently being held. Again, questions must be limited to facts that relate to a very specific and immediate threat to public safety.

The Public Safety Exception first came to light in a New York case involving a suspected rapist named Benjamin Quarles. The victim told police that she’d just seen Quarles enter a supermarket and that he was carrying a gun. Officers then went inside the store and, after a brief foot chase up and down the aisles, captured him.

When officers searched Quarles they didn’t find the weapon. Therefore, worried that a loaded gun was somewhere within the public area of the store and that anyone, including a child, could be harmed, officers immediately asked their suspect what he’d done with the weapon. Quarles indicated the gun was near some milk cartons and said, “The gun is over there.”

Officers did indeed find the weapon and then read the Miranda Warning to Quarles before asking questions pertaining to the alleged rape.

The trial court, though, excluded Quarles’ statement about the gun and his possession of the weapon, because officers didn’t advise him of his Miranda rights prior to asking about it. Appellate courts also agreed with the lower court’s ruling. However, the U.S. Supreme Court first found that Miranda is not a right according to the constitution. Instead, the court stated, Miranda is designed to provide protection for the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. On this basis they decided the very public location of the weapon posed an immediate threat to public safety, and that officers had acted appropriately by asking questions that were prompted by a reasonable concern for the safety of the general public.

Since Quarles, the Public Safety Exception to Miranda has been used successfully on numerous occasions where the safety of the public was of first concern. For example, U.S. v. Khalil, U.S. v. DeSantis, and U.S. v. Mobley. And, the Exception is successfully utilized even after a suspect asks to speak to an attorney. Again, this ruling only pertains to an immediate threat to public safety, such as the possibility that explosives may be hidden somewhere where citizens may travel or congregate, such as in the case of the Boston Marathon bomber.

In the Boston case, interrogators wanted to know if more bombs and other weapons existed. They also needed to know if more people were involved in the bombings. If so, it was of immediate concern that officials locate them and stop possible new attacks, so they proceeded without advising Dzhokhar Tsarnaev of Miranda.

However, at no time did the questioning move outside the very narrow scope of the immediate threat to public safety. Once the topic moved toward Tsarnaev’s actual criminal charges/case, investigators then advised him of the Miranda warnings.

The Public Safety Exception has been in place for just over 30 years, since the Supreme Court ruled on the Quarles case in 1984. Reagan was in office at the time.

*Remember, writers, officers only need to recite the Miranda warnings prior to questioning and when a person is in custody. If there is no intention of questioning, then there’s no legal mandate for Miranda (individual department policy may require it, though). Therefore, the stuff you see on TV—spouting off Miranda warnings the second the cuffs go on—is not how it works in real life.