Reading Between the Blue Lines: Racism

It’s been over a dozen years ago since I wrote the first word on this blog, and before I did I made the decision to avoid the really hot and controversial issues, such as gun control, politics, and racial issues. However, today I’m making what is probably a one time exception with this piece on racism. But it’s important to me to air this, at least one time. Still, this is not an op-ed piece. It’s strictly fact based on my own personal experiences and firsthand knowledge.

Before I begin, though, please understand that I am proud to be an American and I still believe in this country. Current issues may not be popular, just, or they simply rub some the wrong way, but the only way to reach a solution is to address it thoughtfully and truthfully. Sure, there are some serious problems right now, but as Americans it is our duty to make things as they should be.

Okay, here goes …

I grew up during the time when schools were segregated. It was a time when whites ruled supreme over water fountains, bus and restaurant seating, and often to be first to see medical professionals.

In the south where I grew up it was common to have a “colored woman” come to the house once or twice a week to clean up after white families. My mother, at the time, was experiencing a few serious health issues so our father set out to find someone to help out. His advertisement didn’t specify a particular race, just someone who could handle household duties to allow my mother time to heal. Annie Mae was the woman who answered the call.

In our house, Annie Mae pretty much raised us kids. Sure, she was there to clean and do the laundry and a bit of cooking, but she also doled out orders that we kids had better follow, or else. Believe me, we adhered to Annie Mae’s rules. Homework was done before we went out to play, and we scrubbed away the sweat-caked dirt rings from our necks before sitting down to one of her delicious meals.

Annie Mae enjoyed watching “her stories,” the soap operas that dominated daytime TV, and no one, and I mean no one, dared to make a sound until the last dramatic moment came to a close. She’d have a glass of iced tea and maybe a cookie or two while perched in the easy chair clinging to each word spoken by Laura Spencer (General Hospital) or Joanne Gardner (Search for Tomorrow). Then, after last of the daily cliffhanging endings she’d head into the kitchen to begin dinner preparation.

Annie Mae loved my younger brother best and spoiled him until he was rotten to the core.

Annie Mae was a black woman who was born and raised in the south. And yes, we knew of the history even though we were Yankee transplants to the south. We knew of slavery and of the difficult and harsh lives black people endured.

One of my uncles owned a house that Harriet Tubman used as part of her Underground Railroad. I was nearby, at the home of my grandparents when conspirators intended to blow up a courthouse where H. Rap Brown was to be tried for inciting race riots. I definitely knew the story.

We loved Annie Mae, unconditionally, and we didn’t for one moment see her as someone of a different race. To us she was merely a large woman with a smile as wide and bright as the keys on a new Steinway piano. She was a wonderful, loving woman who simply answered a “help wanted” ad, and who was very good at what she did. Most of all, she was family to us. She gave us hugs when our grades were good and threatened to switch our bottoms when they weren’t.

One day, when I was in the 7th grade, our studies were interrupted by the principal’s voice booming from the loudspeaker that hung above the wall-to-wall chalkboard at the front of the classroom. He announced that starting the next year, 8th and 9th grade students would be reporting to a newly-formed junior high school—what was then the “black high school.”

Well, the panic that set in among many of the students and their families was like that associated with the bread and milk aisles of grocery stores when snow or a hurricane is in the forecast. Actually, during the first week or two after the announcement it was more like the paper products and disinfectant aisles at grocery stores during the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. Yes, that bad and that frenzied.

There was a mad rush, one that I couldn’t for the life of me understand, to enroll masses of white kids in private schools, even if it meant transporting children to the next county. Some were sent to military schools. All to avoid having to attend school with the “negras,” a term many of the locals in those days used when referring to African Americans.

Part of the reaction to integration was evidenced by the frequent billowing clouds of smoke that rose from behind the tree line at the back of the old drive-in theater. I knew it was the KKK who were there burning a cross while spewing hateful words. My parents didn’t approve and did their best to keep that sort of thing from us. But we knew. All the kids knew. And we speculated who’s faces were behind the white, pointed hoods when, as a group, they sometimes marched down the main street following their leader, a figure wearing a bright red getup. What I didn’t know was why they burned the crosses each Friday night.

What was so doggone bad about black folks? I just didn’t get it.

The first day of school the following year was a big change for all of us. One of the first things I learned was that some of the black kids didn’t want to attend school with white kids any more than some of the white kids wanted to go to their school. But they didn’t have the option of tucking tail and running off to a private school because there were none for them to attend. They were stuck with us.

Kids, though, made the transition without a single problem, and we did so quickly. New friendships were formed and the sports teams were integrated for the first time ever. A few of them went on to win regional and state championships. Band members and cheerleaders worked things out among themselves, and life went on.

Not the same for the parents, though. Some refused to allow their kids to attend school functions, band trips, and “oh, hell no” my child will not shower with “them” after gym class and football practice. But, kids continued to move forward in spite of parents’ attempts to hang on to the way things used to be.

We just didn’t see the big deal about the different races. We were all kids and we were friends.

Now, let’s turn a few pages on the calendar to my time with a southern sheriff’s office, and to the real point of this piece.

The issue of race separation was alive and in full swing there at the sheriff’s office, and it was shocking to me because many of my fellow deputies were some of the same people I’d known in high school and junior high. A few were on my football team. We’d worked together to win championships, blocking and tackling the same people. Again, we’d been friends.

Therefore, and needless to say, I was equally surprised and shocked to see the duty schedule and how the deputies were assigned. Simply put, blacks worked with blacks and whites worked with whites. Rarely were the two mixed on any given shift. As a result, the friendships we’d known just a few years before were not as close as they once were. The races simply didn’t mix, not there anyway. And, the ranking deputy, a captain, on the “black crew” made it known that he didn’t like white people, and the same was true in reverse for the ranking white deputy, also a captain.

When the African American deputies hauled a person of color to the jail, the offender more often than not received a super stern lecture about shaming their race with their bad behavior.

With all of that said, though, I was the “crossover” deputy because I was often assigned as the token white guy to work with the black deputies. There was no tension between us whatsoever. We were all law enforcement officers on the job and great friend when off-duty. I trusted them with my life and they trusted me with theirs. And it came to just that a few times.

Our boss, the county sheriff created racial tension because of the manner in which he handled the scheduling of deputies.

This same sheriff created another type of discrimination by refusing to allow women to carry firearms or to work as patrol officers. He believed a woman’s place was in the office answering phones or working as dispatchers or jailers/corrections officers. Female deputies were not permitted to attend the police academy.

Now let’s turn a few more pages on the calendar to the time when I’d made the transition to a city police department. There, race didn’t seem to be an issue. Everyone—all ethnicities—worked together and we backed one other when the times were tough.

However, I soon discovered that the same wasn’t true regarding one particular officer. I first learned of this trouble when I was working internal affairs cases. A citizen reported that a white officer was targeting black people, especially regarding traffic offenses. The citizen asked if we’d review the officer’s stats to see if his suspicions were correct. I did, and he was. In fact, the officer had written very few traffic tickets for white people, and those who did receive a summons were typically from outside the city. But the number of summons for people of color was through the roof.

I asked the officer about the stats and his reply was that he couldn’t explain it. So, I did what IA folks do, I sent in an informant—an attractive young woman (he considered himself a ladies man). On their first meeting (she was wired), she brought up race issues and the officer quickly told her, “I hate n*****s. I see one coming my way and they’re gonna get a ticket. N*****s, n*****s, n*****s, I hate all of them.”

Needless to say, the officer lost his job. But what about all the people who’d received traffic tickets? Worse still, the department then had a huge image problem associated with racism. All it takes is one bad apple and the rot spreads through the community like a plague. And, of course, there were similar issues of black officers doing similar things to white citizens. It happens. People are people. They do what they do. Cops are no different than you or your neighbor.

Someone asked me just today if cops are trained to pull over cars with black people inside. I responded by saying this … “Regarding the training of police officers, which includes treating everyone fairly. Any actions other than that are solely those of individuals.

Racism is not a reflection of officer training any more than the actions of any person within other groups of people, including families. Serial killers do what they do yet we don’t accuse their entire family group of having the privilege of earning a bonus when the killer takes a life.

When an officer does something morally wrong or illegal it’s totally against the grain of their training.”

During our police academy training it was mandatory that we learn and understand the meaning behind the Law Enforcement Code of Ethics. Each morning, before the day’s instruction began, we stood and recited the Pledge of Allegiance and then remained standing while reciting the Code of Ethics. We did this as a group, with one loud and collective voice. The Code of Ethics was firmly pressed into our minds. We were taught to live and work according to the code.

Law Enforcement Code of Ethics

As a Law Enforcement Officer, my fundamental duty is to serve mankind; to safeguard lives and property; to protect the innocent against deception, the weak against oppression or intimidation, and the peaceful against violence or disorder; and to respect the Constitutional rights of all persons to liberty, equality and justice.

I will keep my private life unsullied as an example to all; maintain courageous calm in the face of danger, scorn or ridicule; develop self-restraint; and be constantly mindful of the welfare of others. Honest in thought and deed in both my personal and official life, I will be exemplary in obeying the laws of the land and the regulations of my department. Whatever I see or hear of a confidential nature or that is confided to me in my official capacity will be kept ever secret unless revelation is necessary in the performance of my duty.

I will never act officiously or permit personal feelings, prejudices, animosities or friendships to influence my decisions. With no compromise for crime and with relentless prosecution of criminal, I will enforce the law courteously and appropriately without fear or favor, malice or ill will, never employing unnecessary force or violence and never accepting gratuities.

I recognize the badge of my office as a symbol of public faith, and I accept it as a public trust to be held so long as I am true to the ethics of the police service. I will constantly strive to achieve these objectives and ideals, dedicating myself before God to my chosen profession … law enforcement.

Anyway, the point of this rambling concoction is to point out that, yes, racism exists in law enforcement, no doubt. Just as it does within other professions and walks of life throughout the country.

I despise racism from any side, and I truly do not like seeing how race divides the nation. I especially don’t like seeing people exploiting or fabricating racial issues in order to sell newspapers, magazines, TV shows, etc., especially when they do it no matter how badly it harms others.

How serious is racism today? Well, I’ll leave that one for you to ponder. Remember, I don’t offer opinions on racism, religion, gun control, and other hot button issues. They’re poisonous topics. Besides, my purpose is to provide factual information to aid writers in bringing realism to their stories.

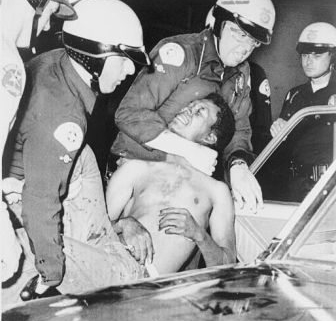

Rodney King said it best when he asked, “Why can’t we just all get along?”

*Please do not use this blog as a forum to argue racial or political agendas, gun control, religion, or cop bashing. Let’s keep the conversation civil, as always. Otherwise, I’ll simply delete your comments.

Brings back lots of similar memories for me. Different names, same story.

I do have a question I’d like explained by someone wit your experience and knowledge. Why was the killing of George Flynn, who had a very long delay and elaborate funeral procession, etc. in the media but there was never any mention of Captain Dorian who was a retired Captain, with 5 children and 10 grandchildren. Shouldn’t we be mourning and conscientious that this works both ways? I’m confused a felon’s death was glorified and a retired Captain LEO was not. Thank you!

My husband and I have learned so much and enjoyed PD Live. To us we saw black and white LEO’s working together and arresting black and white “suspects.” We saw how hard one day/night of work is; the chasing on foot, the strength needed to contain someone on meth, etc. We never saw racism and I don’t think it was censored. It was real and so many others need to see the community building that so many of these officer’s work on every single shift. Thank you for sharing this supportive and vital information.

Thank you for sharing your experiences, Lee.

Thank you for a reasonable voice

Pardon my typos. I need more caffeine.

Thank you for posting this, Lee! The next time someone tells about racist cops, I will point them to this blog post. Thank you, too, for reply to my FB post to set the record straight for the person who shared a post about racist cops on my page. I knew you would shut down that conversation with facts — and you did!

I read your article and I know where you’re coming from… the world should go forward, but how? We’ve all been raised in different areas and placed in unique situations. I was born in Chicago in the late 50’s and moved to Kansas City in the 60’s. I was a seventh grader when the schools integrated for sports. Football games were played at each others schools, but only players traveled. The school boards felt that because there was an unrest going on it would keep things calm, I remember thinking it was horrible, cruel. But then, you are a twelve year old white girl who never did anything to anyone, and yet your mom is driving you and a girlfriend home after a volunteer shift at Research Park Hospital in Kansas City and she stops at a red light. Two black boys carrying bats run up to the car, one jumps on the hood and the other starts opening the passenger door and while the one’s smashing in the windshield, you’re being yanked out by your arm because these boys want the car. The second I get lose with the help from my friend, my mom hits the gas and goes through the light. The boy on the roof jumps off unharmed and we get through the light, barely missing getting hit. A small incident that should easily slide from this old 64 year old’s mind but to this day, I am scared to heavens by African American men. I do nothing to offend them, I will never be disrespectful, but I also have never taught my children or grand children anything other than we love everyone no matter what is the color of their skin. And then two years ago, my granddaughter is on a fieldtrip with some foreign exchange students in New York. There is six of them. Two girls and four boys, all of them are between eighteen and twenty, when they are passed on the street by four African American boys who make guns signs at them and calling them all sorts of crude words. How, please tell me, how do we learn to trust and move forward with these children who grow into men? They want us to stand forward and yell out that Black Lives Matter, but there is still to many of Everyone on both sides who need to change.

Very well-written and illuminating post, Lee. I grew up in a blue-collar city in the integrated North. This was a long, long time ago. I had no idea what was going on in the rest of the country until the 60s. My father was a foreman in a shoe factory. His close friend was a black man who followed him to California to work with him to set up the shoe factory in the San Luis Obispo prison. They were close until my father died. It was a time before 24 hour news. I’m not sure we even had a TV in the early days. What a culture shock when I moved to the South. I hope I live long enough to see the changes everyone is talking about, but some things are so ingrained in people, it will take time. At least for the hundredth time, it is out in the open, but this time seems different. I hope it is.

I was a 4th-grade teacher in a mostly minority elementary school in Seattle, in the 1960s. One time we teachers were asked to indicate how many black kids were in our classes. We had to go back to the classroom and deliberately count them, because we didn’t see our students as black or yellow (we had a lot of Japanese kids) or white (and we didn’t have many of them). Once you know people, you forget their skin color.

Thank you for sharing. I am not and never have been in law enforcement, but I have participated in a Citizens Law Enforcement Academy and experienced ride-alongs. All the men and women I have met there have given me a true appreciation for the patience and professionalism of officers both there in that department and in general. Like you, I grew up in the north and was absolutely appalled when I visited an aunt living in the south and saw the demeaning way she treated her “colored” ladies who I thought were awesome ladies. This all makes me very sad.

Thank you, Lee. Being a police officer or deputy is hard under the best of times.