An Officer’s Perception: Sound Before Sight, Motion Before Color, and Color Before Shape

“Perception is key. How did the officer perceive the encounter? Did she fear for her life or the life of others?”

Before we delve into the topic of perception, please allow me to set the stage by using an experience from my past. I apologize in advance for rehashing the tale, but its use here perfectly illustrates the information below.

Many of you have heard me speak about the deadly shootout I was in back in the 90’s. Others have read the story here on this blog. In both I tell of the involuntary engagement of a “slow motion switch,” and the switching-off of all sounds.

The shooting seemed to occur in slow motion while in a vacuum where sounds were not permitted to enter.

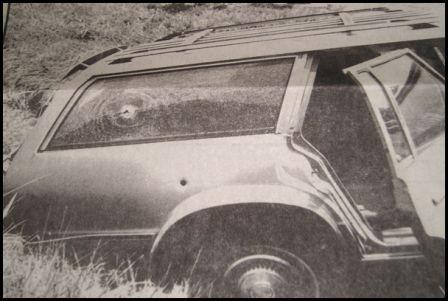

FYI – Pictured above is the robber’s car. I fired the round that penetrated the side and rear glass of the car. At the time, the robber had already begun shooting but the only part of his body I could see was his head. That view was through both panes of glass. My round struck the side of his head. He immediately went down, but almost immediately returned to his feet and resumed shooting.

The large hole in the side of the car just above the wheel well was fired by a rookie officer who was fresh off his field training program. The round was fired from a shotgun. The “slug” was later found in the rear compartment, inside a duffle bag filled with clothing.

To learn more about slugs and what happens when they strike an object, including a human, please click to watch the video below.

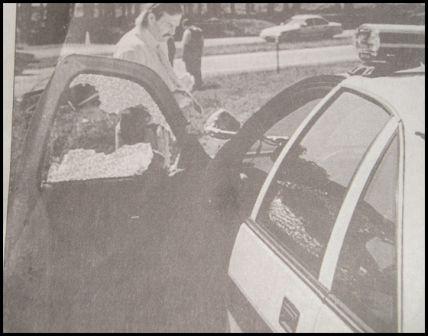

Sights, Sounds, and Auditory Exclusion

FYI – Pictured above: A police car destroyed by gunfire. That’s me in the foreground, with the porn star/cop mustache and my sweaty hair pulled behind my ears. A state agent who’d responded to assist stands behind me near the shoulder of the highway. The suspect’s vehicle is pictured in the distance, directly to my rear. My partner’s unmarked vehicle is seen parked on the opposite side of the median, top right. He’d been in court when he learned of the shooting and had arrived on-scene at the conclusion of the incident.

It was an extremely hot August day and I’d worn a suit. I was preparing to go to court when the call came in, a 10-90—robbery in progress. Mere moments prior to the news reporter taking this photo, I’d killed a man.

FROM MY EARLIER ARTICLE:

“The sound of his gunshot activated my brain’s slow-motion function. Time nearly stopped. It was surreal, like I actually had time to look around before reacting to the gunshot. I saw my partners yelling, their mouths opening and closing slowly. Lazy puffs of blue-black smoke drifted upward from their gun barrels. I saw a dog barking to my right—its head lifting with each yap, and droplets of spittle dotted the air around its face.”

During the exchange of gunfire, I saw the mouths of partners moving and I saw a dog barking, but I did not hear either. The reason I didn’t—auditory exclusion.

Auditory exclusion, like it’s first cousin, tunnel vision, can and does often occur during moments of intense stress, such as life-threatening situations including shootouts or potential shootouts. Actually, guns don’t have to enter the picture for these stress-induced phenomena to occur. However, that’s the focus of this article so that’s the path we’ll travel today.

Stress can interfere with our physiological ability to receive and act on information

In very simple terms, stress can interfere with our physiological ability to receive and act on information received by the brain. Basically, we’re wired to survive and we do so by fighting or fleeing and sometimes freezing in place/not reacting during dangerous situations.

Typically, when faced with danger our bodies automatically increase the release of adrenaline and cortisol, which produces an uptick in heart rate, blood pressure, breathing rate, pupil size, perspiration, and muscle tension. Blood flow to the brain, heart, and large muscles is accordingly increased. However, fine motor skills that require hand/eye coordination begin to deteriorate. This decrease in the functionality of fine motor skills allows the continuation of the more effective (at the time) gross motor skills that help when running or fighting.

One way our bodies react to intense stress is to induce inattentional blindness, a phenomenon that reaches across all senses, including vision (tunnel vision) and sound (auditory exclusion). In short, the brain processes only what the person/officer is focused on, such as a potentially deadly threat. In my case, it was a bank robber who was firing a gun at me and I know that auditory shutdown is a very real thing during high-stress situations. Again, this is from my own personal experience.

NOTABLE POINTS REGARDING PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO STRESS

- Optical affinity can occur—increased ability to see things at 20 feet and beyond while closer objects may seem blurry, if seen at all. The same is true for near shutdown of periphreal vision. The latter is due to vasoconstriction of the blood vessels on the periphery of the retina (tunnel vision).

- Perceptions are often distorted, such as the ability to correctly perceive a danger.

- Sounds are processed by the brain faster than what we see. Touch is the next fastest, and smells reach the brain the quickest.

- Motion is recognized faster than than color, and shape is slowest of all sights processed. Yellow is the fastest color we can identify. Darker colors being the slowest.

- Furtive movement – done in a quiet and secret way to avoid being noticed (Webster’s).

- During stressful encounters, such as those involving deadly force, furtive movements (see above definition) are sometimes perceived incorrectly, such as the movement of hands holding a dark object whose shape somewhat resembles a firearm. but understandably so when factoring in physiological phenomena such as auditory exclusion and tunnel vision.

I See Colors. Or Do I?

Remember, darker colors are identified at a slower rate than bright colors, acute vision at closer distances is greatly decreased, sounds have all but ceased to exist, adrenaline and heart rate are higher, officers are trained to fight not flee from danger, and officers are trained to react to threats. And all of this occurs in a the blink of an eye. There is no time to sit down, discuss, plan, and map out the premium response. This is wholeheartedly in contrast to the armchair cop experts who chime in after the fact with the uninformed, misinformed, social-media-educated, and inexperienced “cop’s are too quick to shoot”comments.

- Our minds, during stressful situations, see what they expect to see. We expect a man suddenly pulling a dark object from his pocket after repeatedly telling him to not put his hands in his pocket, all while knowing he matches the description of a guy who’d just shot and killed four people, well, our minds are telling us he’s going for a gun.

If the object he brings from his pocket is dark, such as a cellphone, a vaping pen that looks like a gun barrel, especially when held like a gun and pointed at officers, a BB gun that’s nearly identical to the officer’s duty weapon, or even a bare hand that comes up and out of pocket rapidly, and the movement is in contrast to the officer’s direction and expectations, and it all occurs within a split second, well …

Remember, sound is perceived before sight, motion is perceived before color, and color is perceived before shape. These differences can and do greatly affect how an officer perceives and processes what’s unfolding in real time. And, those perceptions will definitely affect and/or control the officer’s response(s).

I can say from experience that during a potentially life-threatening situation, barking dogs, screaming officers, sirens, and gunshots are sometimes the loudest sounds you’ll ever NOT hear.

After an intense shootout with an armed bank robber, I shot and killed the man (68 rounds were exchanged—I fired 5). That’s him above as emergency medical personnel treat him.

Even today, at this moment seated here at my desk, I can hear the deafening quiet of that morning. And I still view parts of the scene in slow motion.

Click here to read about the shootout.

By the way, not once during the entire shootout did I or the other officers smell the odor of cordite lingering in the air. Why not? Because the stuff hasn’t been around since the end of World War II. So please, please, please stop writing it into your stories.