Realism in fiction is important, when it’s needed and when placed in the proper context. The ability to weave fact into fiction is a must. But writers must have a firm grasp of what’s real and what’s made-up before attempting to use reality as part of fiction. Otherwise, the author is offering readers fiction as reality, and that’s a fact. Or is it fiction?

The above paragraph is as clear as mucky pond water, right? Well, that’s the sort of muddy writing readers must wade through when writers don’t conduct proper research before diving into to write their next story. For example, confusing a semi-auto pistol with a revolver, or a shotgun with a rifle. Those are the sorts of things that cause writers to lose credibility with their readers. A great example of this is in a current book I read a few weeks ago, where the main character racked a shotgun shell into the chamber of her rifle. Silly writer, shotguns shells are for shotguns, not rifles. Therefore, one does not “rack” a shell into the chamber of a rifle.

The writing in the book was absolutely wonderful … until I read that single line. At that point, as good as the book had been, as I continued to read I found myself searching each paragraph for more errors.

Anyway …

Have you done the unthinkable? Are there words in your latest tale that could send your book straight to someone’s “Wouldn’t Read In A Million Years” pile? How can you avoid such disaster, you ask? Fortunately, following these four simple rules could save the day.

1. Use caution when writing cop slang. What you hear on TV may not be the language used by real police officers. And, what is proper terminology and/or slang in one area may be totally unheard of in another. A great example are the slang terms Vic (Victim), Wit (Witness), and Perp (Perpetrator). These shortened words are NOT universally spoken by all cops. In fact, I think I’m fairly safe in saying the use of these is not typical across the U.S.

2. Simply because a law enforcement officer wears a shiny star-shaped badge and drives a car bearing a “Sheriff” logo does not mean they are all “sheriffs.” Please, please, please stop writing this in your stories. A sheriff is an elected official who is in charge of the department, and there’s only one per sheriff’s office. The head honcho. The Boss.

All others working there are appointed by the sheriff to assist him/her with their duties. Those appointees are called DEPUTY SHERIFFS. Therefore, unless the boss himself shows up at your door to serve you with a jury summons, which is highly unlikely unless you live in a county populated by only three residents, two dogs, and a mule, the LEO’s you see driving around your county are deputies. Andy was the sheriff (the boss) and Barney was his deputy.

All others working there are appointed by the sheriff to assist him/her with their duties. Those appointees are called DEPUTY SHERIFFS. Therefore, unless the boss himself shows up at your door to serve you with a jury summons, which is highly unlikely unless you live in a county populated by only three residents, two dogs, and a mule, the LEO’s you see driving around your county are deputies. Andy was the sheriff (the boss) and Barney was his deputy.

3. The rogue detective who’s pulled from a case yet sets out on his own to solve it anyway. I know, it sounds cool, but it’s highly unlikely that an already overworked detective would drop all other cases (and there are many) to embark on some bizarre quest to take down Mr. Freeze. Believe me, most investigators would gladly lighten their case loads by one, or more. Besides, to disobey orders from a superior officer is an excellent means of landing a fun assignment (back in uniform on the graveyard shift ) directing traffic at the intersection of Dumbass Avenue and Stupid Street.

4. Those of you who’ve written scenes where a cocky FBI agent speeds into town to tell the local chief or sheriff to step aside because she’s taking over the murder case du jour, well, grab a bottle of white-out and immediately begin lathering up that string of goofy words because it doesn’t happen. The same for those scenes where the FBI agent forces the sheriff out of his office so she can remove his name plate from the desk and replace it with one of her own along with photos of her family and her pet guinea pig. No. No. And No. The agent would quickly find herself being escorted back to her “guvment” vehicle.

The FBI does not investigate local murder cases.

I’ll say that again.

The FBI does not investigate local murder cases. And, in case you misunderstood … the FBI does not investigate local murder cases. Nor do they have the authority to order a sheriff or chief out of their offices. Yeah, right … that would happen in real life (in case you can’t see me right now, I’m rolling my eyes).

Believable Make-Believe

Okay, I understand you’re writing fiction, which means you get to make up stuff. And that’s cool. However, the stuff you make up must be believable. Not necessarily fact, just believable. Write it so your readers can suspend reality without stopping in their tracks to wonder if they should, even if only for a short time. If your character carries a rifle that accepts shotgun shells by “racking” them into the chamber, then you must devise a reason for that to become reality—your character is a wacky scientist who invented the new-fangled long gun, for example. Your readers must believe you and your characters.

Your fans want to trust you, and they’ll go out of their way to give you the benefit of the doubt. Really, they will. But, for goodness sake, give them something to work with, without an encyclopedic info dump. Provide readers a reason to believe/understand what they’ve just seen on your pages. A tiny morsel of believability goes a long way.

Still, if you’re going for realism then please do some real homework. I say this because you certainly do not want readers to barely make it halfway through the first chapter of your latest gem when when they suddenly toss it into my WRIAMY pile (Wouldn’t Read In A Million Years).

It’s sometimes painfully obvious when a writer’s method of research is a couple of quick visits to crappy internet sites, and a 15-minute conversation with a friend whose sister works with a man whose brother, a cab driver in Dookyboo, North Carolina, picked up a guy ten years ago at the airport, a partially deaf man with two thumbs on his right hand, who had a friend in Whirlywind, Kansas who lived next door to a retired security guard who, during a Saturday lunch rush, sat two tables over from two cops who might’ve mentioned a crime scene … maybe.

Please, if you want good, solid information, always speak with an expert who has first-hand knowledge about the subject. Not a person who, having read a book about fingerprinting or bloodstain patterns, suddenly believes they’re pro and hits the writers conference circuit teaching workshops. Sure, they may be able to relate what they’ve read on a page, however, those mere words are not the things writers need to breathe life into a story. Reading about bloodstains is not the same as standing inside a murder scene, experiencing the sights, sounds, smells, and emotions felt by the person who’s there in person. The latter is the true expert who can help a writer take their work to the next level, and beyond.

So, is there a WRIAMY pile in your house? Worse … have you written something that could land one of your tales in someone’s “Wouldn’t Read In A Million Years” pile of unreadable books? If so, perhaps it’s time to change your research methods.

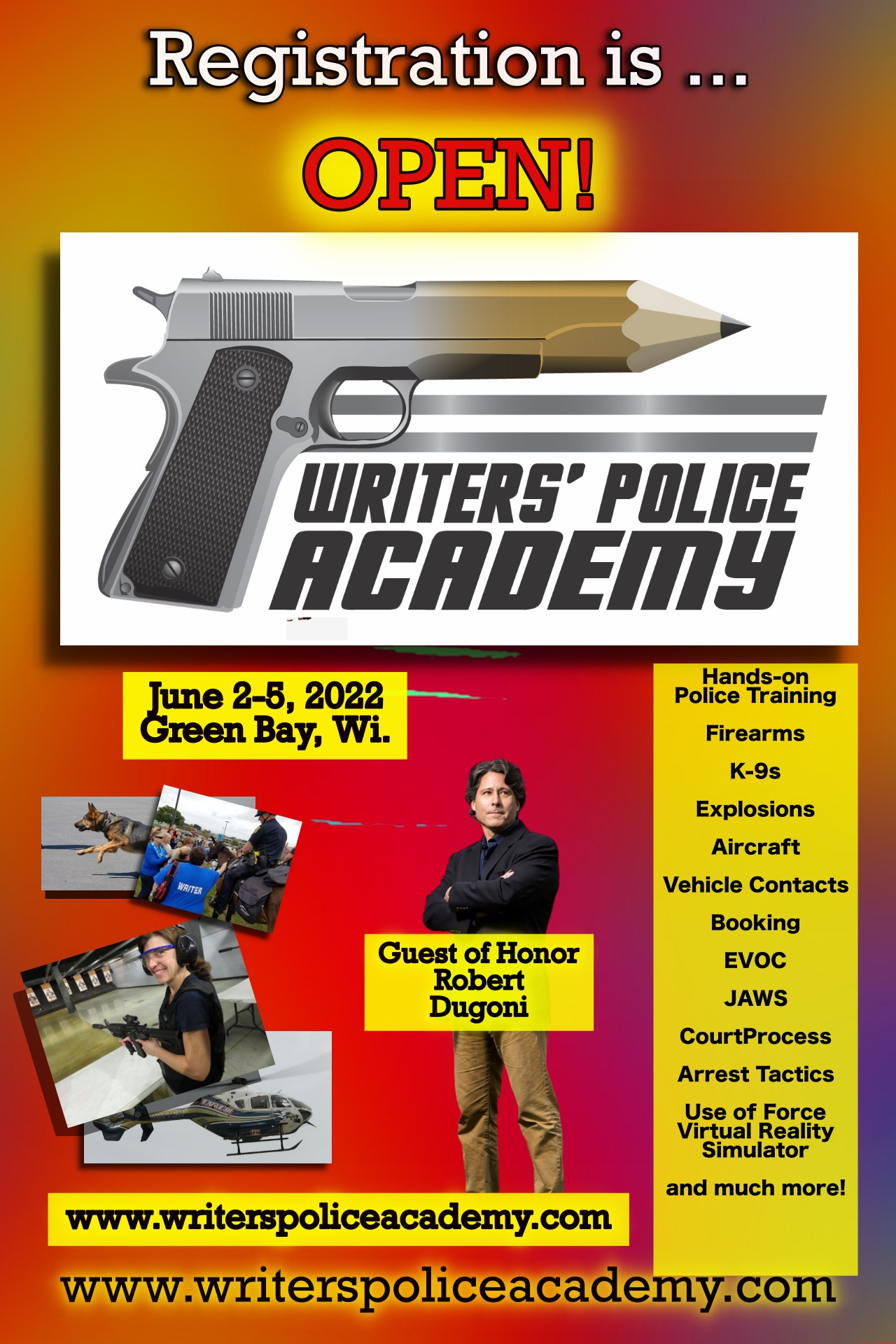

A great means to assist in adding realism to your work is to, of course, attend the Writers’ Police Academy! Registration for the 2022 WPA’s 14th anniversary blowout is now OPEN! You will not want to miss this thrilling experience. It is THE event of the year! Sign up today, and please bring a friend!

You know what I mean—the karate chop to the wrist which forces the bad guy to drop his weapon. How about this doozy … shooting the gun out of the villain’s hand. I know, it’s goofy and unrealistic. So yeah, those things, the things that are not only far-fetched, they’re downright silly.

You know what I mean—the karate chop to the wrist which forces the bad guy to drop his weapon. How about this doozy … shooting the gun out of the villain’s hand. I know, it’s goofy and unrealistic. So yeah, those things, the things that are not only far-fetched, they’re downright silly.