Female blowflies lay eggs, hundreds of them, on moist and juicy decaying matter that’s rich in microbes. These egg-laying sites include, among others, rotting food and the decomposing corpses of animals and humans.

Immediately after hatching, the creepy offspring of their fly parents—maggots—go to work using enzymes and bacteria to break down their food source into a mouthwatering broth.

Blowfly maggots consume their tasty meals much in the same way as gluttonous Sunday afternoon diners at all-you-can-five-dollar-buffets—heads down and without stopping to breathe.

Maggots, though, have an advantage over human buffet-eaters. They’re able to enjoy their feasts while simultaneously breathing through their specially adapted rear ends. Humans, however, are forced to come up for air at least once or twice during a roadside steakhouse feeding frenzy.

In addition to having poor table manners, maggots are a useful tool for homicide investigators. In fact, the first known instance of flies helping out in a murder case was during the 13th century, when Chinese judge Sung T’zu investigated a fatal stabbing in a rice field.

Flies Don’t Lie

At the scene of the murder, judge Sung T’zu instructed each of the workers to lay down their sickles. Soon, attracted by the smell of blood, flies began landing on one of the sickles, but not the others. Sure, the murderer cleaned their weapon prior to the judge’s arrival, but the faint odor of the victim’s blood was still present. It was clear to T’zu who’d committed the killing. In 1247, T’zu wrote about the case in the book The Washing Away of Wrongs, the oldest known book on forensic medicine.

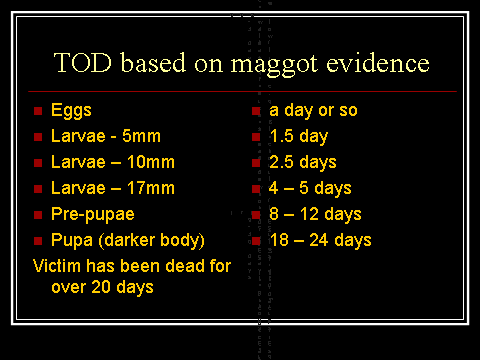

Today, in murder cases, a maggot’s rate of growth can help estimate time of death. For example, when detectives find maggots on a body that are in their early larvae stages, when they’re 5mm in length, officers then will have a pretty good idea that the victim has been deceased for only a day and a half, or so.

When maggots ingest human tissue as nourishment, they simultaneously absorb remnants of substances previously consumed by the deceased, such as illegal and prescription drugs, and poisons. Subsequently, traces of those substances are retained within the bodies and exoskeletons of the maggots.

An insect’s hard external skeleton is made of chitin, a substance that’s similar to the keratin protein from which hair is formed. Since an insect’s chitin stores consumed toxins for a long time, and blowfly maggots shed their exoskeletons twice as it passes through each of three larval stages, a toxicology analyses of those exoskeletons could be helpful in determining the drug use of the victim, poisoning as a murder weapon, and more. This is an especially important tool when working with skeletal remains. In fact, a forensic analysis of insects is more dependable than hair as a means to detect drug use immediately prior to death.

Mummy-“Flied”

How long are substances (toxins, etc.) retained in an insects exoskeleton? Shed fly puparial cases been used for toxicological studies of mummified bodies found weeks, months, an even years after death. Some scientists believe it’s possible to detect drugs in the insects associated with ancient skeletal remains. After all, cocaine has been discovered in the hair of 3,000-year-old Peruvian mummies, so why not the same for the bugs who once feasted on those bodies?

Most evidence, of course, comes from live maggots collected from the body at the crime scene. Those specimens are gathered by crime scene investigators and transported to a forensics laboratory for testing. The trick is keeping the wiggly maggots alive until an analysis is performed.  Therefore, some scientists recommend that crime scene investigators stock cans of tuna as part of their evidence collection kits.

Therefore, some scientists recommend that crime scene investigators stock cans of tuna as part of their evidence collection kits.

Pop the top on the can and maggots are then able to feed on the tuna until they’re properly secured and handled by a qualified forensic entomologist.

It’s also important to place maggots in a container with air holes (even though they breathe through their butts, they’ve still got to breathe to survive).

Now, who’s having tuna for lunch today?

Yum …