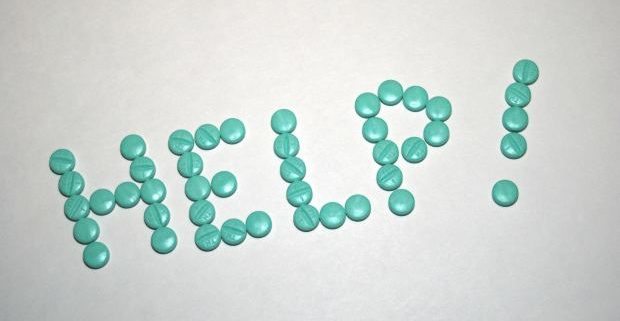

Police and the Mentally Ill: He’s Off His Meds and I Need Help!

In more than half of all instances when a mentally ill person commits a violent crime, the victim is a family member, a friend, or an acquaintance of the mentally ill suspect. And, those family member/victims have no choice, usually, but to call the police for help. Unfortunately, until recently police received very little training when it came to dealing with the mentally ill. In many areas that sort of training is still minimal, if any.

Police officers, especially those working in patrol, are jacks and jills of all trades. They’re expected to quell disturbances, disarm those who intend to harm or kill others, defend the lives and property of citizens, enforce traffic laws, serve arrest warrants, investigate crimes, and much, much more. And they receive a certain amount of basic training that’s required to do all of the above. Of course, more intensive training opportunities are available, if they have the time and the department can spare them from their scheduled duty.

Uniformed officers respond to numerous calls during their 8-12 hours shifts, and these calls range from barking dog complaints to murder and everything you can imagine in between—domestic troubles, bad checks, fights, stabbings, shots-fired, B&E, trespassing, shoplifting, robbery, car crashes, lost children, abduction, arson, assault, theft, drunk driving and, well, you name it and they’ve responded to it…over and over, time after time.

Each call, no matter how it’s labeled, is different. The people are rarely the same as those they encountered on similar calls (with the exception of the repeat “customers”), settings vary, weather differs, and the actions of witnesses and suspects are often unfamiliar or uncommon. In other words, patrol officers never know what to expect when they arrive on-scene. Even a repeat offender could act differently each time he interacts with law enforcement. Drugs and alcohol are factors that definitely come into play in many of these situations.

Add all of these uncertainties to an encounter with a mentally ill person who decides to attack someone, and the situation takes on an entirely new perspective. Violence can escalate in the blink of an eye, even during encounters with people who are healthy in both mind and body, and officers are used to dealing with that sort of instant violence. They do what they have to do to keep people safe and to make an arrest, but they do not possess the psychic ability of being able to instantly diagnose mental illnesses.

The Police Chief magazine reports that 7-10% of all police encounters involve someone with a mental illness.

Even when officers do recognize that someone is mentally ill their options for helping that person at that precise moment are slim. In fact, their alternatives when responding to a call where an act of violence was committed by a person with a mental illness are basically to either let the suspect go or arrest them and take them to jail. Obviously, like the call I once responded to where a mentally ill man hacked and chopped his sister-in-law with an ax because she wouldn’t stop cleaning the house long enough to go to the store to buy him a pack of cigarettes, cannot be allowed to go free. Nor can police turn loose a suspect who attacks or shoots at them.

Officers often have to use force when arresting mentally ill subjects and doing so increases the risk of injury to both the officer and the suspect. But they simply cannot stand there idle while the mentally ill person continues to harm himself and/or others.

Responding officers are obviously not trained psychologists or psychiatrists, therefore an on the spot diagnosis is not available. Neither is the option of taking someone who’s accused of a violent crime straight from the street to a mental institution. So jail it is. Keep in mind, too, that not all mental illnesses are easily recognizable in the few minutes or seconds officers have when assessing and reacting to various situations.

To help with the problems associated with police response to incidents involving mentally ill persons, agencies are now employing new tactics, such as forming crisis intervention teams consisting of specially-trained officers who can facilitate emergency mental health assessments along with transportation to a mental health treatment facility, if that’s an option. Remember, though, that many treatment facilities will not accept those who have pending charges for violent offenses, and that leaves those individuals to make their way through jail, court proceedings, and finally prison.

In 2006, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) estimated there were 705,600 mentally ill people in state prisons, 78,800 in federal prison, and 479,900 in local jails.

I’ve seen first-hand what the mentally ill population looks like in state, federal, and local facilities, and it’s not a pretty sight. Have you watched the hit TV show The Walking Dead? Well, that’s a fine example of what evening pill call looks like at a low custody federal prison, where highly-medicated prisoners stand in long lines outside the medical department waiting to receive their next dose of zombie-inducing medications.

Keeping these inmates “doped-up” and “calmed-down” until their release back into society where they’ll no longer have access to those medicines is indeed the norm. And, without a means of generating income (it’s difficult enough for a former inmate who’s healthy to find a job and housing) these recently released felons will go without their much-needed medication (some become addicts while in prison), and the process begins once again.

“Nine-one-one, do you have an emergency?”

“Yes, my son just got out of prison and he’s trying to kill me with a butcher knife. He’s off his meds and he’s acting all crazy. Help me, please!”

And so it goes.

*By the way, the mentally ill man I mentioned above, the one who hacked his sister-in-law with an ax, was released from prison a short time prior to the incident and no longer had access to the medications he’d received while incarcerated. It was only a few days after his release when he brutally attacked the woman, completely chopping off her right hand and repeatedly hacked at her head and back until small bone fragments and blood and spatter painted the floor and nearby walls, lamps, and furniture. Her three small children were in the room at the time and witnessed the violent and bloody attack. They were hiding under the bed, five- or six-feet away from their mother’s body, when I arrived. They, too, were covered from head to toe with smears and splatters of, well, you know.