Fireworks: Behind The Scenes With Pyrotechnician Joe Collins

Everyone likes the Fourth of July–fireworks, food, and fun. For some of us, it’s a time of hard work, thrills, and sometimes danger.

For the past seven years, I have been a professional pyrotechnican working in the fireworks display industry.

The BATF—Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, abbreviated to ATF has defined various classes of fireworks. Consumer fireworks are most often classified as Class 1.4G—stuff you can buy in stores and shoot in your back yard—state and local laws permitting.

Most display fireworks are classified as Class 1.3G. I have a federal license to posses and shoot Class 1.3G fireworks as long as I am working for the display company that sponsored my license.

Now that the legalities are out of the way, let’s get to the fun stuff!

Fireworks

The cone at the bottom of a typical shell is where the lift charge is located which is simply a bag of black powder enclosed in a protective cone of cardboard.

five inch shell

Tied into the bottom of the shell is quickmatch which is black match—cotton string covered or soaked in black powder that is enclosed in a paper tube or plastic tube all along the whole length. The tube forces the fire down at a very high speed (approximately 30 feet per second). This is what we light to “lift” the shell from the mortar, either electrically or by fire.

quickmatch

quickmatch closeup

You can see the blackmatch in the close up above.

The whole shell is wrapped in craft-type paper secured with glue.

On the top is a loop of string that is used to keep the quickmatch in the right place and in larger shells is used to lower the shell into the mortar.

To lift a shell, you need a mortar. They come in various sizes and are often held together to accomplish certain effects—the one below is called a finale rack—a series of mortars tied together that all lift shells at the end of a show.

finale rack

As you can see, there are several different sizes and the company I work for has a few of them.

mortar storage

Single mortars are what you see below and are often buried into the ground to stabilize them.

mortar

And, they come in a wide variety of sizes.

single mortar storage

big mortar

Our mortars are constructed of fiberglass which doesn’t cause the shrapnel problems if they blow out like the old steel mortars. They are also cheap to make and are lightweight.

mortar closeup

Shells blowing apart mortars happens more often than you would think and makes for an exciting experience when you are close to them.

This is why we wear protective clothing: it’s mandatory that you wear blue jeans, a cotton shirt, a helmet with a face shield and ear protection, gloves, and safety glasses.

safety gear

The most complex of shows to set up and shoot are electrically fired. Some shows are also required to be electrically fired—like those set to music and every barge shoot.

wired barge

The shells are ignited by an electric match which, when an electric current is applied to it, ignites a combustible compound. Think of a model rocket igniter but much more powerful.

e-match

The matches are wired into slats which are screwed to the top of the mortar racks.

slat

slat closeup

The slats plug into cables.

slat cables

As you can see, it takes more than a few cables to wire up the shows.

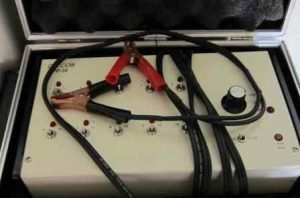

The cables are plugged into a firing panel.

firing panel back

Firing panels come in a wide variety of configurations and sizes, some small:

small firing panel

Note the battery cables—most shows are fired using a car battery.

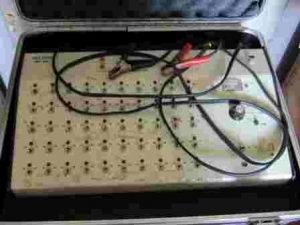

And some large-bigger shows are fired with larger panels.

100 shot firing panel

You may only notice that there are fifty switches. There are two banks. When you’ve fired the first fifty-shells, you flip a switch and you can shoot the second bank of shells.

bank switch

The really difficult part is making sure that the shells will fire when you flip the switch. There is a test function on the firing board which you can see below.

test and firing switch

There is an LED over each switch and if it doesn’t glow when you hit the test switch, then you have to figure out what is wrong with the circuit which can be very tedious to track down.

firing switches

Once the shells are loaded, wired, tested and otherwise ready to go, you can sit back and enjoy the show.

Next time we get to my favorite way of shooting a fireworks show—hand fired.

I can’t even begin to imagine the work that goes into the yearly displays – it makes my head swim.