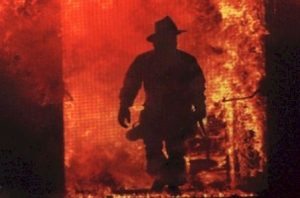

Firefighters have one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Walking into a house fire that could reach 1000 degrees in under a minute (that’s not a typo) or a chemical fire that may reach double or triple that temperature in seconds, while battling smoke inhalation as well, means a firefighter’s life depends on being supplied with the best equipment that money can buy. Without the proper gear, firefighters can’t stay inside a burning structure long enough to rescue victims or fight the fire successfully.

So, what is the right gear that keeps them safe and still allows them to do their jobs?

Tim Fitts, a veteran firefighter in North Carolina, and Coordinator of certification classes for firefighters and rescue squads at Guilford Technical Community College, demonstrated his gear on a 95 degree day in September. Fire isn’t selective about the weather, so it’s a good thing for us that firefighters train and work under all kinds of conditions.

The firefighter uniform is generally called ‘turnout gear’ by firefighters because they turn it inside out when not in use, so that they can step into it quickly and pull it on/up when the fire bell/siren sounds. Firefighters need to get completely dressed in about a minute, so any safe system that will speed up the process is used. Some guys pull on the boots and pants, grab the rest of the gear and finish getting dressed in the truck as it pulls out of the fire station.

The official name for the gear is Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

Parts of the firefighter uniform:

While on the job at a fire or rescue operation that might result in a fire, most firefighters will wear these pieces of clothing:

- Boots, insulated with steel toes and steel shank

- Cotton t-shirt

- Gloves, insulated leather

- Helmet, with neck flap and eye protection

- Hood, Nomex

- Jacket, insulated, with Velcro and spring hooks

- Pants, insulated, with Velcro and spring hooks, with extra padding and pockets

- Suspenders

These three hoods are each made of different fabrics:

- Kevlar blend

- PBI/Kevlar

- Nomex

Firefighters put a hood on before the jacket, so that it sits properly on the shoulders. They tend to wear two hoods to protect against a flashover, giving their heads the extra defense needed in the intense heat. If a flashover occurs, the firefighter will have about two seconds to get out of the building. If the hoods are not providing enough coverage, it will feel like 1000 bees stinging the ears at one time – it’s too hot to stand. It’s time to get out.

The helmets are made of thick, heat resistant plastic and often include Kevlar or Nomex flaps for the ears.

Firefighters are taught to fight fires on their knees (not while crawling) so the extra padding helps cushion the wear and tear on the knees.

In addition, the firefighters put on:

- Airline and pressure gauge

- Flashlight

- Positive pressure mask

- PASS device

- Radio

- SCBA shoulder straps, airtank bottle and backpack frame

The PASS device (Personal Alert Safety System) is a personal safety device used by firefighters entering a hazardous environment – a burning building. When the firefighter does not move for 30 seconds, it makes a loud, shrill, really annoying sound, letting others in the area know that something is wrong.

The mask on the left is a newer model, the one on the right? Older. There has been an upgrade in technology for the plastic in the mask, developed because at high temperatures, the old plastic would fail (melt). It was the weakest part of the uniform. The new version will not fail as quickly.

Note that even the air tank is protected with a fire retardant fabric.

The idea is to be protected from the fire and to be able to breathe safely while he/she works. The positive pressure mask on the SCBA (Self Contained Breathing Apparatus) gear keeps the toxic air out as much as possible by allowing the tank air to flow continuously, even if the firefighter is not inhaling. By the way, the tanks are full of compressed air, not oxygen.

Most of the clothes have reflective tape so that the firefighter can be seen more easily through the smoke and low light/darkness. Some departments are large enough that they use color-coded reflective tape in order to tell the full-time firefighters and the volunteers apart.

The uniforms are sized to the individual firefighters, so that when they bend over, there is at least a two-inch overlap with the fabric pieces, and no skin is exposed to the crippling, blistering heat.

Hip boots of years ago, are now old school because of the area of the body they left unprotected from heat. Now the boots have steel toes and shanks and are calf high or knee high in length.

When fully dressed, the firefighter is wearing about 70 pounds of equipment. Add more weight for the tools they have to carry – picks, axes, etc – needed to fight the fire.

After ten years, all turnout gear must be thrown away. It wears out because of repeated exposure to the intense heat and toxic elements. Many large, active fire departments dispose of the clothing after only five years, because of their more frequent use and improvements in technology.

Firefighting gear is not fireproof. It is fire retardant.

Some of the clothing has 3 layers, each layer performing a different function. People can only tolerate temperatures to 135 degrees, so the specialized fabrics extend the time available to do the job. Firefighters get very uncomfortable at 250 degrees, and the time limit for the firefighter at that point is about 30 seconds to reach someone and get out. One of the firefighters at Command keeps track of the men/women – where they are in the structure and how long they’ve been working the fire.

Nomex degrades at 400 degrees, so needs to be used in addition to other fabrics if fighting a structural fire. It tends to split when the wearer is running. When combined with Kevlar, it becomes more flexible and the fabric breathes a bit better.

PBI degrades at 1100 degrees, allowing a much better chance for the firefighter to stay safe while fighting a house blaze. It stays intact in the extreme temperatures and allows the firefighter extra time to get to a victim and then get out.

Gortex helps shed water

Heat goes through each layer a bit at a time. Each layer is a necessary barrier, in its place to protect the firefighter and keep his body from getting hotter than is safe.

After fires, all of the clothing needs to be taken apart and washed, because everything in a fire is carcinogenic. Hmm…that means that the entire time a firefighter is working the fire, his equipment has to protect him from the flames and the smoke, as well as anything else thrown into the air, both in the active fire and in the area outside the building.

Some fire Captains insist that the clothing be stored away from the sleeping area at the station, because it may still contain toxins even after being washed. If you get a chance to visit a Fire Station, you might be able to tell where the gear is kept, before you ever reach the room. The smoky odor is sharp and unforgettable.

Cost of Basic Turnout Gear (approximate)

- Pants, jacket, gloves – $1,150.

- Boots – $175.

- Helmet – $150.

- Nomex hood – $60.

- PASS device – $300.

- Airpack with mask – $4,500.

Tim Fitts told us about the testing going on at NC State’s College of Textiles, in the search for better, more effective, fire retardant fabrics.

To see a demonstration of how a firefighter’s uniform reacts to fire, click here for NC State’s PyroMan video:

http://www.tx.ncsu.edu/tpacc/heat-and-flame-protection/pyroman.cfm

For a demonstration of how quickly heat from a flame penetrates protective layers before reaching the skin, click here for NC State’s PyroMan animation:

http://www.tx.ncsu.edu/tpacc/heat-and-flame-protection/pyroman-animation.cfm

Every second counts when rescuing you or your pets in a fire. We know that a simple house fire can fully engulf an 8’x10’ room in 90 seconds. That’s not a typo. If the firefighters are on the scene before that happens to the entire house, they need as much lead time as possible in order to keep a rescue operation from becoming a recovery operation. That’s when the best turnout gear on the market is worth every dime.

*Photos by Patti Phillips, taken at Guilford Technical Community College, NC, during The 2014 Writers’ Police Academy.

Thanks to Tim Fitts for generously sharing his knowledge and expertise. Tim is a veteran firefighter and Fire Occupational Extension Coordinator at GTCC. He’s in charge of all Con Ed certification and non-certification classes in Fire and Rescue subjects to members of NC fire departments and rescue squads. Any errors in fact are mine, not his.

* * *

Patti Phillips is a transplanted metropolitan New Yorker/north Texan, now living in the piney state of North Carolina.

Her best investigative days are spent writing, attending The Writers’ Police Academy, cooking, traveling for research and playing golf. Her time on the golf course has been murderously valuable while creating the perfect alibi for the chief villain in her novel, One Sweet Motion. Did you know that there are spots on a golf course that can’t be accessed by listening devices?

Ms. Phillips (writing as Detective Charlie Kerrian) can be found at www.kerriansnotebook.com. Her book reviews can be read at www.nightstandbookreviews.com