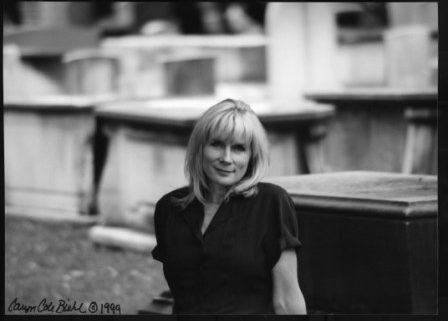

Dr. Katherine Ramsland: Inside the Archives of Rome’s Crime History

Dr. Katherine Ramsland has published 34 books and over 900 articles, and is the chair of Social Sciences at DeSales University, where she teaches about forensic psychology, profiling, serial murder, and forensic science. Her latest book is The Devil’s Dozen: How Cutting-edge Forensics Took Down 12 Notorious Serial Killers, and in August, she will publish The Real World of a Forensic Scientist, with and about Henry C. Lee. Recently, she went to Rome to see, among other things, the Criminology Museum there.

Inside the Archives of Rome’s Crime History

In Italy, they urge you to take a vacation with the phrase, “Buy an emotion!” At least, that’s how it translates. I think I bought several when I walked into the Italian Ministry of Justice’s three-story collection of torture instruments, insanity treatments, and evidence exhibits. Before getting on the plane to go, I had researched crime history for Rome and was disappointed to learn that most of the exhibits from the nineteenth-century criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso were in Turin. I had included him in several books and had hoped to see his work on degeneracy up close.

Experienced in the methods of phrenology (reading head formations), Lombroso had made numerous measurements and photographs of criminal offenders. He was convinced that certain people were born criminals and could be identified by specific physical traits: bulging or sloping brow, apelike nose, close-set eyes, and disproportionately long arms. In other words, delinquency manifested in someone’s appearance as a physiological abnormality. (Hey, don’t scoff; we still do this with our cinematic bad guys, to set them apart in some recognizable way from the good guys.)

Although the main part of Lombroso’s legacy was too far away, I did discover that about two miles from my temporary Rome abode was the Criminology Museum, so I made a point of looking for it. Few tourist books mention it and even though I had an address on Via del Gonfalone, the terra cotta colored building on a narrow side street near the river was not obvious; compared to other Roman museums it was quite humble and unobtrusive. Nevertheless, I found it and when I made it clear to the staff, who spoke only Italian, that I was a member of the forensic community, I was warmly greeted and ushered inside to the recreated torture chambers. (They didn’t lock me into one, they just wanted me to start in the right place.)

Rome’s penal institutions are much older than anything we have in the U.S., and while many of our laws derived from their legal structure (as well as the word, ‘forensic’), for quite a few centuries they investigated crimes without benefit of forensic analysis. In other words, they relied on “crime logic,” which was often influenced by politics. (Even today, logic alone can get us into trouble.)

The earliest museums devoted to crime and prisons were annexed to scientific laboratories, with the first exhibit of prison products (things made by prisoners) in 1885, for the International Penitentiary Congress in Rome. The museum in which I stood got its start in 1931, with the aim of making the results of criminological research available to the public. Interestingly, the Zanardelli Code of 1889 gave university chairs the right to remove body parts from dead inmates for study. (I should have mentioned that I’m a university chair – maybe I could have taken something home besides a lava vase from Pompeii and some Italian coffee.)

In one area, I did see a display about Lombroso and his work on the criminal degenerate, but by then I’d found other stuff that was far more fascinating. There were exhibits for items related to forgery, espionage, organized crime, illegal weapons, and of course, murder. I even discovered the story about a juvenile serial killer that I had not heard of — the kid was 14 when he killed five people. This museum also contains quite a few torture instruments (iron maidens, spiked collars, gossip bridles), along with clothing that executioners wore (red cloaks) and their implements for execution. I was drawn to the exhibits about the “confraternities” of priests that were dedicated to walking with the prisoners to their executions. Their job was to prepare them for a peaceful death and also to bury the corpse. (Incidentally, the process of torture was referred to as a “penal bath.” Nice euphemism.)

Iron maiden

One of the most famous stories from Rome involves the execution of an entire family, which was depicted here in a series of water colors. Francesco Cenci, an unscrupulous man, was found dead at the foot of the cliff below his estate. Overhead, a broken balcony indicated he’d fallen through, hitting his head on the rocks below. However, forensics indicated that his wounds had been made by a sharp implement, not a rock, and bloody sheets in his room bore this out. Cenci’s adult daughter, Beatrice, and his second wife, Lucrezia, had been living at the castle for a few months, victims of his violent moods. The court believed that the family, in cahoots with two servants, plotted together to kill Cenci and stage it as an accident. They were all sentenced to death. One of the servants died under torture and the other was shot trying to escape. That left the family members to go to the gallows in a public procession.

On September 11, 1599, Beatrice’s twelve-year-old brother Barnardo was taken up the scaffold and positioned to watch. Beatrice and Lucrezia were both beheaded with a broadsword, while a bludgeoning ball smashed the head of Giacomo Cenci, Beatrice’s other brother. His body was then quartered and his parts were hung up on butchers hooks on the walls. The bodies remained there in the execution yard until evening, while Bernardo was tossed into a prison cell for life. In the museum, I saw the beheading sword (which looked pretty dull), along with the torture instruments that had extracted the confessions (except for Beatrice, who insisted she was innocent.) Later, I went to see the execution yard, as well as the bridge where Beatrice’s ghost supposedly walks around with her severed head.

I was most intrigued with the exhibit on criminal asylums, since I had written about this in Beating the Devil’s Game. There was a compassionate movement in Europe near the end of the nineteenth century to establish crime as the result of disease, especially in the case of those who were clearly psychotic. Alienists viewed such criminals as deviant people in need of protection, care, and a cure. The first place in Italy given over to this reform was a sixteenth-century monastery, and other asylums sprang up after that in more traditional places, but Italy was the location for numerous international conferences on criminal insanity. The exhibit was small, but intense. In fact, the entire museum was professionally rendered, inviting the visitor to spend hours absorbed in the stories. The murder room was especially riveting, because the evidence from each crime was laid out behind glass, and the stories behind the crime and investigation were tastefully graphic.

For anyone interested in criminology who lives near, or hopes to get to, Rome, the Website is www.museocriminologico.it. It’s definitely worth a trip.