Dr. Katherine Ramsland – Behind C.S.I.: True Stories

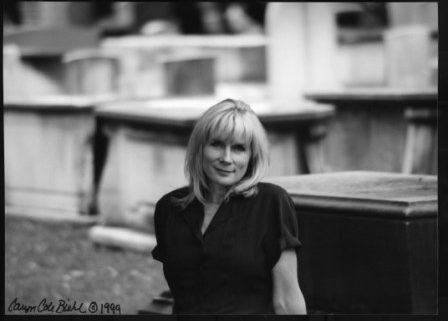

Dr. Katherine Ramsland has a master’s degree in forensic psychology from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, a master’s degree in clinical psychology from Duquesne University, and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Rutgers. She has published thirty-one books, including The CSI Effect, Inside the Minds of Serial Killers, Inside the Minds of Healthcare Serial Killers, Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers, The Human Predator: A Historical Chronology of Serial Murder and Forensic Investigation, The Criminal Mind: A Writers’ Guide to Forensic Psychology, and The Forensic Science of CSI. With former FBI profiler Gregg McCrary, she co-authored the book on his cases, The Unknown Darkness: Profiling the Predators among Us (Morrow, 2003), and with Professor James E. Starrs, A Voice for the Dead (Putnam 2005), a collection of his cases of historical exhumations and rigorous forensic investigation. She has been translated into ten languages; published fifteen short stories and over 400 articles on serial killers, criminology, forensic science, and criminal investigation, and was a research assistant to former FBI profiler, John Douglas (Mindhunter), which became The Cases that Haunt Us (Scribner, 2000). With FBI profiler Gregg McCrary, she wrote The Unknown Darkness, and with James E. Starrs, A Voice for the Dead, about his various historic exhumations. She currently contributes editorials on forensic issues to The Philadelphia Inquirer; writes a regular feature on historical forensics for The Forensic Examiner (based on her history of Forensic science, Beating the Devil’s Game) and teaches both forensic psychology and criminal justice at DeSales University in Pennsylvania. Her most recent book is Into the Devil’s Den, about an undercover FBI operation inside the Aryan Nations (with Dave Hall and Tym Burkey), and forthcoming are True Stories of CSI and The Devil’s Dozen: How Cutting Edge Forensics Took Down Twelve Notorious Serial Killers. In addition, she has published biographies of both Anne Rice and Dean Koontz and penned three creative nonfiction books about penetrating the world of “vampires” (Piercing the Darkness), ghost hunters (Ghost), and the funeral industry (Cemetery Stories). From these experiences, she wrote two novels, The Heat Seekers and The Blood Hunters. Currently she’s working on a book about murders in her local area.

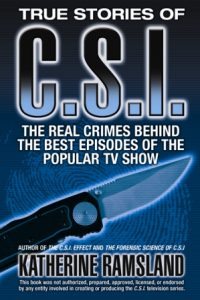

Behind C.S.I.: True Stories

In recent seasons of C.S.I., several episodes featured the clever and elusive “Miniatures Killer.” This offender planned murders in great detail and created tiny but exacting replicas of each crime scene. While many people ask me how much of C.S.I. is based on actual cases, they query most often about this unique series of episodes. I’m always delighted to say that the Miniatures Killer is based on reality – not on the work of an offender but on the vision of an innovative heiress who created the “dollhouses of death” as teaching instruments for police officers. As is often the case, a true story inspired the C.S.I. creators and they added their fictional spin.

Because viewers are often curious about what really happened in some incident, I collected the actual cases that inspired many episodes and wrote True Stories of C.S.I. (Berkley 2008). One of the 25 chapters is devoted to the woman behind the dollhouses, while others describe such notorious offenders as Richard Trenton Chase, Michael Peterson, and Richard Speck, as well as such headline-grabbing incidents as the “rebirthing” homicide in Colorado, the JonBenét Ramsey murder, and our modern-day body-snatchers.

I learned about Frances Glessner Lee when I was researching the history of forensic science for Beating the Devil’s Game. She was the only woman who had made a serious contribution to the field, and she did so against the wishes of her wealthy parents. Indeed, her contribution was so unique and generous she became the first woman invited into the fledgling organization, the American Academy of Forensic Science, and was made an honorary member of the International Association of the Chiefs of Police.

Frances was the daughter of John Jacob Glessner and heir to the International Harvester fortune. During the early 1900s, she aspired to study law or medicine, but her father forbade her from attending a university. Off went her older brother to Harvard, where he met George Burgess Magrath, who hoped for a career in pathology. Magrath often visited the Glessners at their thousand-acre New Hampshire estate, where he mesmerized Frances, a fan of Sherlock Holmes, with stories about death investigation. Once he became a medical examiner, he confided to her the need for solid training for death investigators. She asked what she could do and Magrath encouraged her to assist with developing a prestigious flagship program at Harvard.

In 1931, Lee provided an endowment and library for Harvard’s Department of Legal medicine. But then she did more. She knew that inexperienced police officers often committed errors when trying to determine manner of death, largely due to missing the clues, so to mitigate this, she devised a practical solution: build crime scenes on which they could practice – in miniature. She dubbed her project the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.” Setting aside the second floor of her mansion as a workshop, she filled one room with doll-size furniture. Then she hired two fulltime carpenters to craft the small buildings. From cabins to three-room apartments to garages, each was fashioned to scale from her design. The doors and windows actually worked, with shades that rolled up and working locks with mini-keys.

They built three Nutshells per year, each of which cost the same as an average house in those days. Lee made the dolls by hand, using a cloth body stuffed with cotton BB gun pellets and bisque heads. She painted the faces and stitched the clothes, adding sweaters and socks knitted on straight pins. Once each doll was ready, Lee would decide just how it should “die” and proceed to stick a knife in one, drown another, or hang one in a noose. On each, she would paint decomposition.

To create each crime diorama, she blended several stories, sometimes going with police officers to crime scenes or the morgue, sometimes reading reports in the newspapers, and often injecting fiction. She preferred enigmatic scenarios, where one had to examine all the clues before deciding on a conclusion.

Once Lee had several dollhouses ready, she made them part of the weeklong law enforcement seminars she sponsored at Harvard twice a year. One day of each seminar was set aside for work with the Nutshells. Participants had limited time to look at each crime scenario, take notes, and report back to the others about the evidence they saw. By the time Lee finished her ambitious project, she had nineteen Nutshells.

In each scene, she included items that were not readily apparent, such as a subtle smudge of lipstick on a pillow slip. What might seem to be a suicide, for example, would look different when a key item was noted – a fresh-baked cake and a load of freshly-laundered clothing beside a woman’s body on the kitchen floor. Other scenarios included a bound prostitute with a sliced throat and a man hanging in a wooden cabin.

By 1949, some 2,000 doctors and 4,000 lawyers had been educated at the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine, and several thousand state troopers, detectives, coroners, district attorneys, insurance agents, and crime reporters had attended Lee’s seminars. They would continue successfully for several more years before the Nutshells were transferred to the Office of the Medical Examiner in Baltimore, MD. After Lee died, her friend, Erle Stanley Gardner (author of the Perry Mason series), wrote, “Captain Lee had a strong individuality, a unique, unforgettable character, was a fiercely competent fighter, and a practical idealist.” She is truly a role model for females in forensics today and C.S.I. is to be credited for renewing interest in her accomplishments.

Thanks, everyone, for writing. I really admired this woman, and I know that Carol Henderson, of CSI, does, too. There is a photography book featuring the Nutshells, as Camille points out, and some of the photos are posted on my article about Lee on the TruTV Crime Library Website. Thanks for taking the time to read and comment.

As a miniaturist and a mystery writer, I’m a huge fan of Frances Lee.

I have “Nutshell Studies . . .” close at hand in my office, next to Lofland’s “Police Procedure & Investigation.” I see that I need to add a third.

Thanks so much, Dr. Ramsland, for bringing Lee to the attention of a wider audience through this blog.

I knit with 000 needles, small enough for me. I tried Lee’s method with straight pins once and completed 2 rows before calling it quits.

Camille Minichino/Margaret Grace

http://www.dollhousemysteries.com

Hi Guys. Dr. Ramsland is busy with classes for most of the day, but she says she will be checking in from time to time to respond to your questions.

Thank you Dr. Ramsland.

While the television show makes it look like they can solve a crime overnight, the miniture series was a favorite.

The dollhouses are really interesting. Elena, you will have to be specific when you google this. However there are some good sites and pictures if you dig.

Thank you for a great blog !

How serendipitous – Mrs. Lee is on my ‘look up’ list after recently reading a comment about her in one of Erle Stanley Gardener’s non-fiction works.

A fun addition – she grew up in Chicago and her family home is now a museum. Seeing it gives one appreciation where her love of furnishings came from.

Thank you for kick-starting that bit of research for me 🙂

This is fascinating! I vaguely remember hearing about this woman before, but never realized she did so much.