It’s the year 2021. Since last year we’ve all endured COVID, working from home, quarantine, wildfires, flooding, more COVID, lockdowns, shutdowns, layoffs, tornados, earthquakes, masks, vaccines, the loss of loved ones, riots, a mess overseas and, well, you know. Pick a disaster and at least some of us have been there. Some lost jobs and others found new employment. It’s been a stressful time for all of us. Even Denene, my wife, has a new job having recently accepted a position as Director of Microbiology and Immunology at college of medicine. Perfect timing, I know.

Anyway, to get to the point, while reading current novels and blogs and news articles, I’ve once again run across the misuse of various cop-type terms and information. As a result, I decided to compile and post a bit of information to help set things straight.

I hope this helps somewhat in your quest to avoid a writing disaster, and to …

Write Believable Make-Believe

Defendant: Someone who’s been accused of a crime and is involved in a court proceeding.

Defense Attorney: A lawyer who represents a defendant throughout their criminal proceedings.

Departure: A sentence that’s outside the typical guideline range. Departures can be above or below the standard range; however, the most common departure is a downward departure, a sentence reduction solely based on the defendant’s substantial assistance to the government. For example, a defendant who spills the beans to law enforcement about the criminal activity of someone else for the sole purpose of obtaining a lesser sentence. In jailhouse/layman’s terms, “a snitch.”

Diminished Capacity: A defendant is eligible for a downward departure (reduction of sentence) if they can successfully prove they suffer from a significantly reduced mental capacity, a condition that contributed substantially to the commission of the offense of which they’re charged with committing. Merely having been under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of the offense is typically not considered grounds for diminished capacity.

* This applies to the defendant only, not the defendant’s attorney, judges, or police officers. Their sometimes reduction in mental capacities is fodder for another article.

Duress: The federal sentencing guidelines allow for a downward departure if the defendant committed the offense because of serious threats, coercion, or pressure. An example is the person who’s been forced to commit a bank robbery by crooks who’re holding his family hostage until/unless he carries out the crime. The courts could/would show leniency by granting a downward departure (or complete dismissal) based upon the fact he was under severe duress at the time of the robbery.

Extreme Conduct: Here, an upward departure from the guidelines range may be appropriate if the defendant’s conduct during the commission of a crime was unusually heinous, cruel, and/or brutal. Even degrading the victim of the crime in some way may apply and earn the defendant a longer sentence that’s typically called for within the sentencing guidelines.

Brutally maiming and murdering federal agents simply because they dared to ask questions (revenge), well, that may be a crime that warrants an upward departure from the typical sentence.

Felony: An offense punishable by a term of imprisonment of one year or longer.

Felony Murder: A killing that takes place during the commission of another dangerous felony, such as robbery.

To get everyone’s attention, a bank robber fires his weapon at the ceiling. A stray bullet hits a customer and she dies as a result of her injury. The robber has committed felony murder, a killing, however unintentional, that occurred during the commission of a felony. The shooter’s accomplices could also be charged with the murder even if they were not in possession of a weapon or took no part in the death of the victim.

Hate Crime Motivation: An increase of sentence if the court determines that the defendant intentionally targeted a victim because of their race, religion, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, disability or even due to their sexual orientation.

Heat of Passion/Crime of Passion: When the accused was in an uncontrollable rage at the time they committed the murder. The intense passion often precludes the suspect/defendant of having premeditation or being fully mentally capable of knowing what he/she was doing at the time the crime was committed.

Indictment: An indictment is the formal, written accusation of a crime. They’re issued by a grand jury and are presented to a court with the intention of prosecution of the individual named in the indictment.

Misdemeanor: A crime that’s punishable by one year of imprisonment, or less.

Obstruction of Justice: Obstruction of Justice is a very broad term that simply boils down to charging an individual for knowingly lying to law enforcement in order to change to course/outcome of a case, or lying to protect another person. The charge may also be brought against the person who destroys, hides, or alters evidence.

For more about obstruction, see When Lying Becomes A Crime: Obstruction Of Justice

Offense Level: The severity level of an offense as determined by the Federal Sentencing Guidelines.

Federal Sentencing Guidelines are rules that determine how much or how little prison time a federal judge may impose on a defendant who has been found guilty of committing a federal crime.

To learn more about these guidelines, go here … So, You’ve Committed a Federal Offense: How Much Time Will You Serve?

Parole: The early and conditional release from prison. Should the parolee violate those conditions, he/she could be returned to prison to complete the remainder of their sentence. Parole, however, was abolished in the federal prison system in 1984. In lieu of parole, federal inmates earn good time credits based on their behavior during incarceration. Federal inmates may earn a sentence reduction of up to 54 days per year. Good time credits are often reduced when prisoners break the rules, especially when the rules broken are serious offenses—fighting, stealing, possession of contraband such as drugs, weapons, or other prohibited material.

Federal prisoners who play nice during their time behind bars typically see a substantial accumulation of good time credit and will subsequently hit the streets much sooner than those who repeatedly act like idiots.

Due to earned good time credit, federal prisoners who follow the rules are typically released after serving approximately 85% of their sentence.

Writers, please remember, there is no parole in the federal system. People incarcerated in federal prison after 1984 are not eligible for parole because is does not exist. I see this all the time in works of fiction.

By the way, this regularly occurring faux pas (incorrect use of parole in novels) brings to mind the dreaded “C” word … cordite. I still see this used in current books. Your characters, unless in works of historical fiction, cannot smell the odor of cordite at crime scenes because the stuff is no longer manufactured. In fact, production of cordite ended at the end of WWII (1945).

After all, you wouldn’t write that the only means of entertainment in a modern home is listening to old-time radio shows, or that today’s foods are kept cool in iceboxes chilled by a 25 lb. block of frozen water. Why wouldn’t we incorporate those things as standards in modern fiction? Because it wouldn’t be believable. After WWII, radios were soon replaced by television. Likewise, iceboxes and the icemen who delivered the ice to individual homes were forced out of service by electric refrigerators.

So why in the world would a modern writer so freely accept newfangled refrigerators and television, but remain stuck in 1945, or so, when cordite use in ammunition became a thing of the past? It’s over. Done. NO CORDITE in modern ammo. It’s not sexy to write something so horribly inaccurate.

Please, please, please, step into 2021 and stop using “stinky information” in your books.

Please read this:

Once Again – Cordite: Putting This Garbage In The Grave!

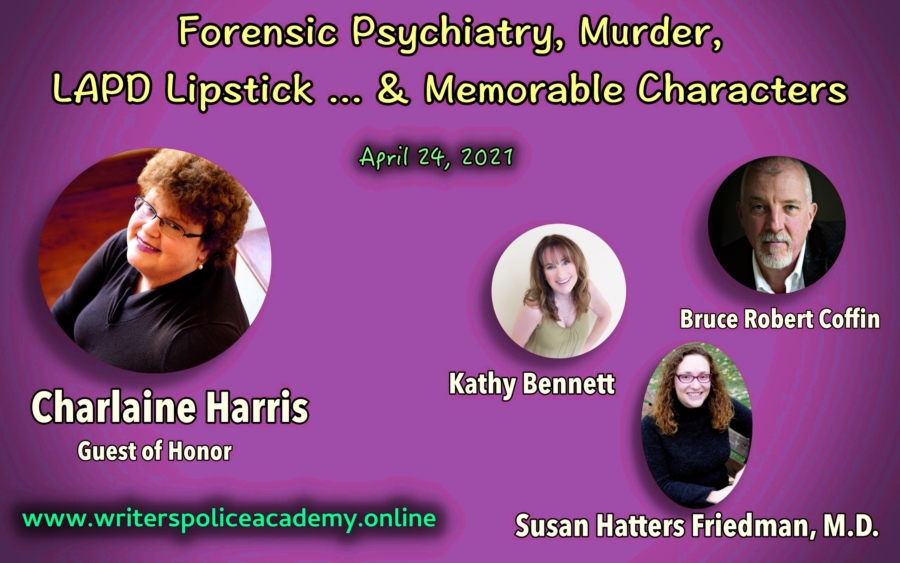

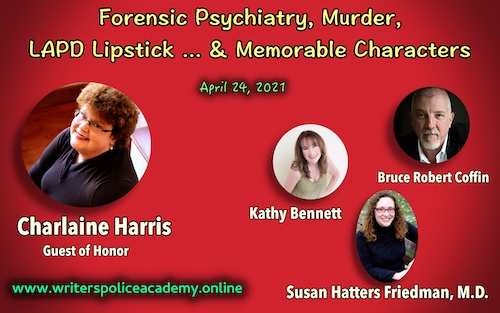

Guest of Honor Charlaine Harris is a true daughter of the South. She was born in Mississippi and has lived in Tennessee, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Texas. After years of dabbling with poetry, plays, and essays, her career as a novelist began when her husband invited her to write full time. Her first book,

Guest of Honor Charlaine Harris is a true daughter of the South. She was born in Mississippi and has lived in Tennessee, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Texas. After years of dabbling with poetry, plays, and essays, her career as a novelist began when her husband invited her to write full time. Her first book, Susan Hatters Friedman, MD

Susan Hatters Friedman, MD Kathy Bennett worked for the LAPD for twenty-nine years. Eight years were spent as a civilian employee, and she served twenty-one years as a police officer. While most of her career was spent in a patrol car, Kathy also worked at the police academy as a firearms instructor, promoted to the position of a field training officer, then worked in the “War Room” as a crime analyst. She promoted again, this time to the position of Senior Lead Officer—where she was in charge of a basic car area within a geographic division. She’s done a few stints undercover and was honored to be named Officer of the Year in 1997.

Kathy Bennett worked for the LAPD for twenty-nine years. Eight years were spent as a civilian employee, and she served twenty-one years as a police officer. While most of her career was spent in a patrol car, Kathy also worked at the police academy as a firearms instructor, promoted to the position of a field training officer, then worked in the “War Room” as a crime analyst. She promoted again, this time to the position of Senior Lead Officer—where she was in charge of a basic car area within a geographic division. She’s done a few stints undercover and was honored to be named Officer of the Year in 1997. Bruce Robert Coffin is the award-winning author of the bestselling Detective Byron mystery series. A former detective sergeant with more than twenty-seven years in law enforcement, he supervised all homicide and violent crime investigations for Maine’s largest city. Following the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, Bruce spent four years investigating counter-terrorism cases for the FBI, earning the Director’s Award, the highest award a non-agent can receive.

Bruce Robert Coffin is the award-winning author of the bestselling Detective Byron mystery series. A former detective sergeant with more than twenty-seven years in law enforcement, he supervised all homicide and violent crime investigations for Maine’s largest city. Following the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, Bruce spent four years investigating counter-terrorism cases for the FBI, earning the Director’s Award, the highest award a non-agent can receive.

Marriage is practically taboo in crime fiction. Rarely do fictional law enforcement officers enjoy the company of spouses or serious relationships. Yes, some are haunted by the tormented spirits of dead husbands or wives, but not living, breathing people. I suppose it’s easier to write a tale about a person who’s single, but cops in the real world do indeed marry, and some do so four or five times since the job truly can wreak havoc on married life. For the most part, though, family life is important.

Marriage is practically taboo in crime fiction. Rarely do fictional law enforcement officers enjoy the company of spouses or serious relationships. Yes, some are haunted by the tormented spirits of dead husbands or wives, but not living, breathing people. I suppose it’s easier to write a tale about a person who’s single, but cops in the real world do indeed marry, and some do so four or five times since the job truly can wreak havoc on married life. For the most part, though, family life is important. There you go, eight pet peeves of many cops who

There you go, eight pet peeves of many cops who

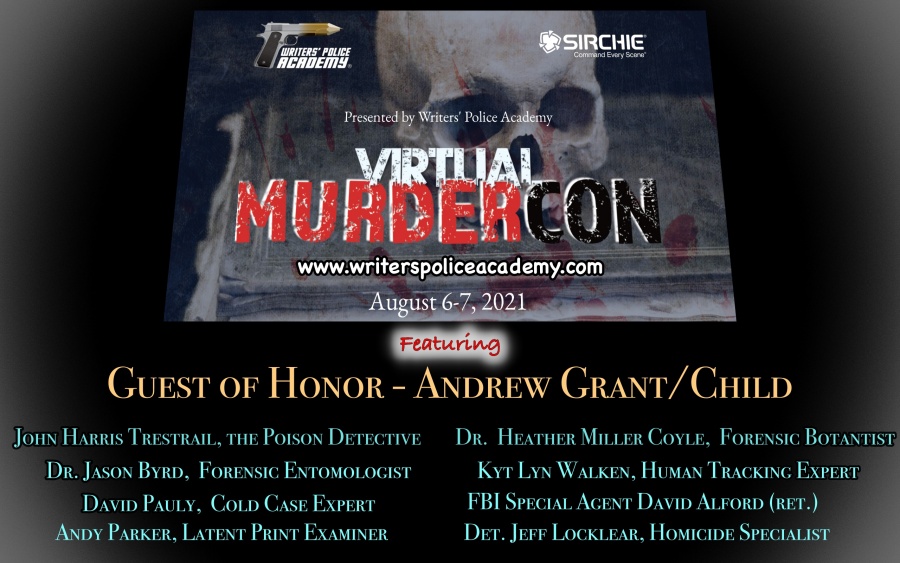

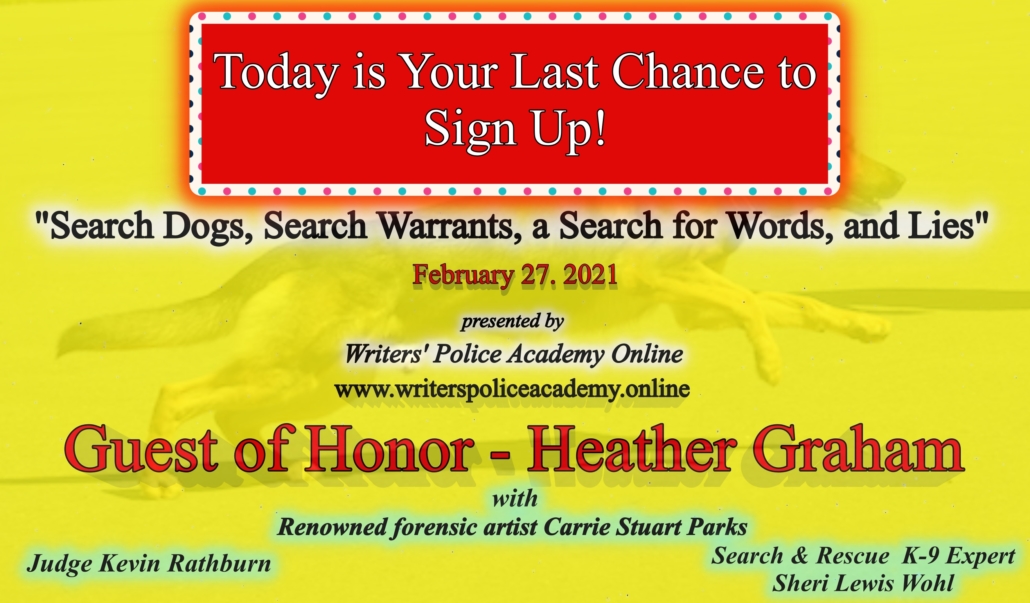

Carrie Stuart Parks is an award-winning, internationally known forensic artist. She travels across the US and Canada teaching courses in forensic art to law enforcement professionals including the FBI, Secret Service, and RCMP, and is the largest instructor of forensic art in the world. Her best-selling novels in the mystery/suspense/thriller genre have garnered numerous awards including several Carols, Inspys, the Christy, Golden Scroll, Maxwell, and Wright. As a professional fine artist, she has written and illustrated best-selling art books for North Light Publishers.

Carrie Stuart Parks is an award-winning, internationally known forensic artist. She travels across the US and Canada teaching courses in forensic art to law enforcement professionals including the FBI, Secret Service, and RCMP, and is the largest instructor of forensic art in the world. Her best-selling novels in the mystery/suspense/thriller genre have garnered numerous awards including several Carols, Inspys, the Christy, Golden Scroll, Maxwell, and Wright. As a professional fine artist, she has written and illustrated best-selling art books for North Light Publishers. Sheri Lewis Wohl is a 30-year veteran of the federal judiciary, a search and rescue K9 handler, and the author of more than fifteen novels, several of which feature search dogs. She is a field ready member of search and rescue in Eastern Washington and for the last nine years, has been a human remains detection K9 handler deployed on missions throughout Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

Sheri Lewis Wohl is a 30-year veteran of the federal judiciary, a search and rescue K9 handler, and the author of more than fifteen novels, several of which feature search dogs. She is a field ready member of search and rescue in Eastern Washington and for the last nine years, has been a human remains detection K9 handler deployed on missions throughout Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Kevin Rathburn became a full-time faculty member at Northeast Wisconsin Technical College in 2000 after serving as an adjunct instructor for nine years. Prior to that, Mr. Rathburn served for ten years as an Assistant District Attorney for Brown County in Green Bay, Wisconsin. In 2004, Mr. Rathburn became Municipal Judge for the Village of Suamico. Mr. Rathburn holds BAs in political science and economics from St. Norbert College (1987) and a JD from Marquette University Law School (1990).

Kevin Rathburn became a full-time faculty member at Northeast Wisconsin Technical College in 2000 after serving as an adjunct instructor for nine years. Prior to that, Mr. Rathburn served for ten years as an Assistant District Attorney for Brown County in Green Bay, Wisconsin. In 2004, Mr. Rathburn became Municipal Judge for the Village of Suamico. Mr. Rathburn holds BAs in political science and economics from St. Norbert College (1987) and a JD from Marquette University Law School (1990). New York Times and USA Today bestselling author, Heather Graham, majored in theater arts at the University of South Florida. After a stint of several years in dinner theater, back-up vocals, and bartending, she stayed home after the birth of her third child and began to write. Her first book was with Dell, and since then, she has written over two hundred novels and novellas including category, suspense, historical romance, vampire fiction, time travel, occult, sci-fi, young adult, and Christmas family fare.

New York Times and USA Today bestselling author, Heather Graham, majored in theater arts at the University of South Florida. After a stint of several years in dinner theater, back-up vocals, and bartending, she stayed home after the birth of her third child and began to write. Her first book was with Dell, and since then, she has written over two hundred novels and novellas including category, suspense, historical romance, vampire fiction, time travel, occult, sci-fi, young adult, and Christmas family fare.