We’ve all seen the reports of innocent men and women who’ve been released from prison—exonerated—due to faulty evidence, cleared by DNA evidence, etc. But what was it about the evidence that robbed people of years of their lives by forcing them sit in a prison cell while completely innocent of the crimes they were accused of committing?

Let’s take a quick peek at the human hair. For many years, law enforcement collected hairs found at crime scenes and then delivered those hairs to their laboratories for examination and comparison (does the hair found match that of a suspect?).

If the examiner took a look under a microscope and then decided the hairs were indeed a solid match then his/her word was good enough for the courts. The suspect must be guilty because the scientist said that positively and without a single doubt the hair placed the defendant at the scene of the crime. Therefore, a jury or judge had all they needed to convict and send a bewildered person to prison.

Well, in 2015 the Justice Department revealed that FBI agents weren’t so sure that hair analysis was the most exact science in the world. In fact, they basically admitted that hair analysis, at best, is inconclusive. They no longer use it as a sole means to build a case against someone.

Santae Tribble was convicted of murder based on the analysis of a hair found at the crime scene. He spent more than 27 years in prison before DNA analysis of the hair proved his innocence. He was awarded $13.2 million in his wrongful conviction lawsuit. A little something for his “minor” inconvenience.

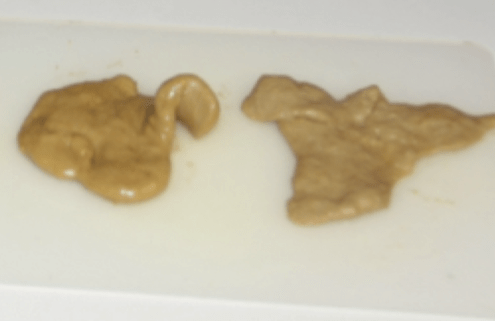

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.).

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.).

Then there are tool marks, tire impressions, footwear impressions, and fingerprints. Yes, there are flaws within the testing of those items as well. Even the golden goose of all evidence—DNA—is not a perfect science.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 2155 people have been exonerated of crimes they didn’t commit. To put that in perspective … innocent people spent 18,750 years in prison due to someone’s error—flawed evidence examination, prosecutor or law enforcement mistake, evidence contamination, flawed procedures, flaws in the law, etc. 18,750 years, gone. Lives wasted.

A great example of how a flawed bite-mark examination sent an innocent man to death row is the story of our friend Ray Krone. Ray was … well, I think I’ll sit back and post Ray’s tale as he told it to me a while back.

Ray Krone Spent 10 Years on Death Row for a Crime He Didn’t Commit

A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by Polly Iyer about a man who had been wrongfully convicted of murder, released, and then framed for a series of murders. As with all good fiction, there were elements of fact in this story. Polly’s description of the impact of wrongful convictions struck a chord with Cheryl, and she sent Polly an email saying so. That email started an exchange that led to me posting on this blog today.

A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by Polly Iyer about a man who had been wrongfully convicted of murder, released, and then framed for a series of murders. As with all good fiction, there were elements of fact in this story. Polly’s description of the impact of wrongful convictions struck a chord with Cheryl, and she sent Polly an email saying so. That email started an exchange that led to me posting on this blog today.

My story isn’t much of a mystery, but it has twists and turns that wouldn’t make it past a fiction editor’s red pencil. Lee thought that it might be of interest to you, so here goes. I’m not a professional writer but I hope that I’ll be able to provide some useful insights into the ripples that result from sloppy police work, ineffective defense counsel, and overzealous prosecutors.

I won’t go into details about my life prior to my arrest and wrongful conviction. It was unremarkable as most lives are, except to the people who live them. I sang in the church choir, was a Boy Scout, and played team sports throughout my school years. I was never in any trouble, never even had detention in school. I grew up in a small town, joined the Air Force, and following my Honorable Discharge remained in Phoenix, AZ, my last duty station. I got a job with the United States Postal Service as a letter carrier.

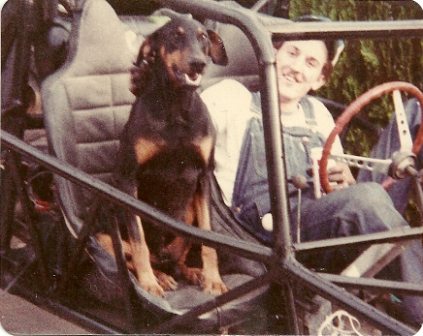

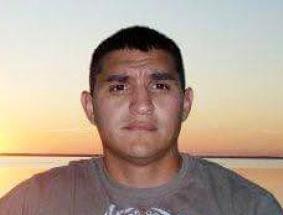

Ray before his arrest for a crime he didn’t commit

At 35, I was single and living the good life. My salary allowed me to buy my own home and have lots of big boy toys—sand rail, Corvette, swimming pool. I had a loving family back in PA, and loyal friends all over the country. Little did I know that I was about to find out just how important those people were.

I’d always enjoyed team sports, and still do. A bar in my neighborhood sponsored volleyball and dart teams, and I played on both. On December 29, 1991, the owner found his night manager, Kim Ancona, on the men’s room floor. She’d been sexually assaulted and stabbed to death. A co-worker told police detectives Kim had said someone named Ray was going to help her close up that night. I had a casual acquaintance with this woman, and knew her only as a bartender and occasional dart player. She was living with a man and as far as I was concerned, that was as good as married and made her off-limits.

Detectives found my name and phone number in her address book and came to see me. It’s important to note at this point that my name and phone number were not in my handwriting or in Kim’s. How they got there remains a mystery to this day. I was questioned by the Phoenix Police, and cooperated—until I realized they were trying to pin this murder on me. The legal wrangling is public record—you can Google my name and read countless stories about my case.

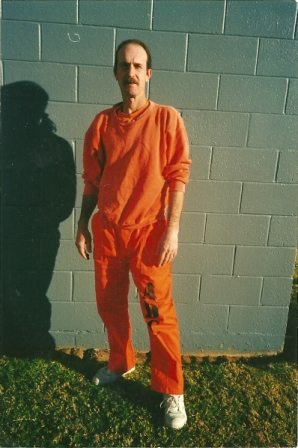

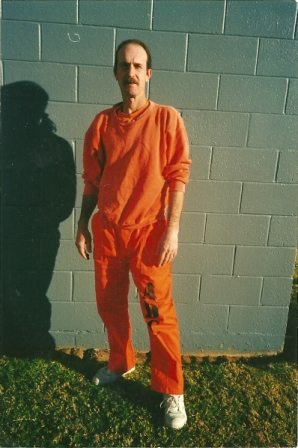

Being the one hundredth person to be wrongfully convicted and sentenced to die, only to be found factually innocent after spending years on Death Row and in prison, put me on the radar of a society that was beginning to question the value of capital punishment. My conviction was based solely on bite mark evidence. Because I refused to show remorse for a crime I didn’t commit, I was sentenced to death. After almost three years on Death Row, I was granted a new trial. I was again convicted, and sentenced to 23 years for the kidnapping, and 25 years to life for the murder. Only a random series of events would free me. Court-ordered DNA would finally free me and identify the real killer. I spent a total of ten years, three months and eight days in prison for something I didn’t do. I was 35 when arrested and 45 when I was exonerated.

Ray as an inmate at Arizona State Prison in Yuma

The life events that other people take for granted were stolen from me, and no amount of money, sympathy or accolades will ever give me a chance to experience them. They are gone forever. Am I bitter? I try not to be—the family and friends who stood by me have helped me adjust and appreciate what I do have. I try not to focus on what I’ve been denied in this life, but what I’ve been given. I’ve learned the hardest way possible the true meaning of “you find out who your friends are.” Despite the love and support of friends and family, I still have moments when I feel rage at what happened to me, even after more than ten years of freedom.

Billboard on I-83 in Harrisburg, Pa.

There have been millions of words written and hundreds of television shows about the impact on men and women who were sentenced to die for a crime they didn’t commit. There are well-documented studies about innocent men and women who were executed in the name of justice. There are other victims of a legal system that penalizes the poor and rewards prosecutors for conviction rates without examining the accuracy of those convictions. Not just the families of the wrongfully convicted, who often lose what little they have in the defense of their loved ones, but the families of the original victim, the new victims created by the guilty party who remains free, their families, the jurors who are denied access to all of the evidence in a case. The list goes on and on—I misspoke when I called it a ripple—it’s a tsunami, wreaking havoc and destruction, and in many cases, is preventable.

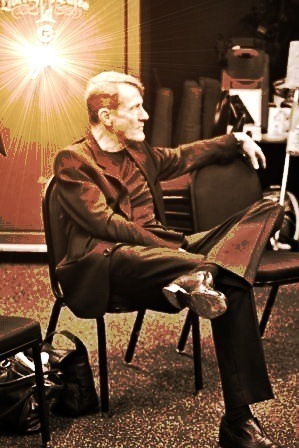

I’m part of a nationally-known group called Witness to Innocence. We have only one membership requirement, but it’s a tough one. You must have been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to die for a crime which you did not commit. Although many of us are unable to speak publicly about what happened to us, many others find it therapeutic to do so. We have spoken in front of groups ranging from high school students to Congress to the United Nations. We share our experiences at law schools, forensics conventions and gatherings of legal professionals—anywhere that telling our stories will help provide insight, and hopefully inspiration.

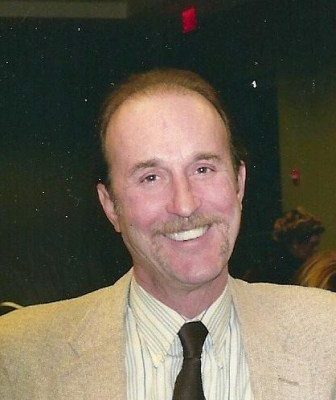

The Witness to Innocence photo above is of only some of the members. Left to right: Ray Krone, Albert Burrell, Kirk Bloodsworth, Gary Drinkard, Randy Steidl, Ron Keine, Delbert Tibbs and Derek Jamison. Each of these men (and our one female member, Sabrina Porter) have stories that defy belief, as do all of the members.

I’m honored to have been invited to address the readers of this blog. For more information about Witness to Innocence, stories of exoneration or speaker’s schedules, please visit www.witnesstoinnocence.org

According to the Innocence Project, since 1989, 353 people have been exonerated of their crimes based on DNA. Twenty of those people served time on death row.

Deputy Sheriff Heath Gumm, 32

Deputy Sheriff Heath Gumm, 32

FMC Devens is situated adjacent to Mirror Lake, just a short drive down the road from Red Tail Golf Club. A hike through the woods to the rear of the place and you’ll cross Sheridan Road and then the George W. Stanton Highway. On the opposite side of the Stanton is the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge. A right on the Stanton takes you to a state prison, past the Great Wolf Lodge, and Stoneville and then Farley. A left and you’d soon be in Cambridge, near Harvard.

FMC Devens is situated adjacent to Mirror Lake, just a short drive down the road from Red Tail Golf Club. A hike through the woods to the rear of the place and you’ll cross Sheridan Road and then the George W. Stanton Highway. On the opposite side of the Stanton is the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge. A right on the Stanton takes you to a state prison, past the Great Wolf Lodge, and Stoneville and then Farley. A left and you’d soon be in Cambridge, near Harvard. Tank tops may be worn during recreational activities in the outdoor or inside recreation areas. Tank tops may not be worn on the compound or in the Food Service area. Sunglasses will not be worn inside buildings unless prescribed by medical staff.

Tank tops may be worn during recreational activities in the outdoor or inside recreation areas. Tank tops may not be worn on the compound or in the Food Service area. Sunglasses will not be worn inside buildings unless prescribed by medical staff.

And this, my good friends, is how little offenses grow up to be big and strong crimes. Well, that, a little luck, and the stupidity of criminals. Fighting in the front yard of the place where you’re running a major drug operation, with an illegal gun in your pocket … yeah, he’s a bright one. And typical.

And this, my good friends, is how little offenses grow up to be big and strong crimes. Well, that, a little luck, and the stupidity of criminals. Fighting in the front yard of the place where you’re running a major drug operation, with an illegal gun in your pocket … yeah, he’s a bright one. And typical.

Detective Michael Doty, 37

Detective Michael Doty, 37 Deputy U.S. Marshal Christopher Hill, 45

Deputy U.S. Marshal Christopher Hill, 45

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.).

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.). A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by

A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by