A couple of years ago I had the pleasure of sitting in on a fascinating lecture presented by two members of the Boston Police Department’s Crime Lab Unit. As with many departments across the country, this highly skilled team consists of scientists and police officers, with the actual crime scene evidence collection performed by the civilian scientists. Here’s a video describing the unit.

A cup of coffee, a piece of toast, a glance at the morning paper, and a leisurely stroll through a bloody crime scene. Sometimes there’s no time for the coffee. Instead, the morning begins with a brisk, adrenaline-filled scuffle with suicidal man who’s crazy-high on methamphetamine, or a lovely peek at a bloated body that’s teeming with hundreds of writhing maggots. That’s how some cops start their day. How about you?

The rest of the day is a piece of cake—drug dealers, shots fired, fighting, lost children, crying mothers, abusive parents, hungry children, murder, suicide, shoplifters, pursuits, fatigue, crack cocaine, addicts, prostitutes, burglars, no lunch, robbers, getting spit on by abusive citizen, battered spouses, drunks, rabid animals, lost pets, remove wild animal in citizen’s garage or basement, bad checks, autopsy, trip to crime lab, traffic accident, speeders, question witness, peeping tom, search woods filled with tons of poison ivy, serve warrants, miss child’s play at school, citizen can’t get furnace to work, dog stuck in drain pipe, citizen locked keys in car, citizen locked herself in bedroom and doesn’t know how to turn button on doorknob to get out, pull unconscious man from burning house, citizen hears prowler, kids throwing water balloons at elderly people, check homes for people while they’re on vacation, testify in court, 4-12 officer calls in sick—must work 8 more hours.

Drug dealers, shots fired, fighting, lost children, crying mothers…

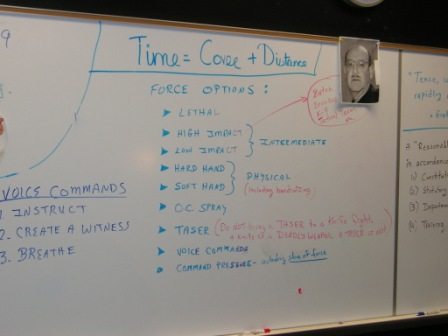

Police officers are forced to make many split second decisions during the course of their careers, and one of those decisions is when to use force. If they choose to use force they’re then faced with deciding which level of force should be employed. Should a Taser be used when a combative suspect is holding a knife? Should the officer go for her firearm if the suspect is swinging a baseball bat at her head? Is an officer ever justified to shoot an unarmed suspect? Are there situations when officers must retreat? All these decisions are made within one-half to three-quarters of a second. That’s about how long it takes the average human to react to a given situation.

Let’s first examine the scenario pictured above. Here, an officer stands facing a knife-wielding suspect who clearly presents a danger. The bad guy is holding an edged weapon (a knife) in the classic “ice pick” position. Years ago officers were taught that a suspect could be shot, and justifiably so, if he were wielding a knife in a threatening manner while positioned within a distance of twenty-one feet (the 21 foot rule) from the officer. The reasoning was that the suspect was without a doubt an immediate, deadly threat. Officers were taught that they’d not likely survive this scenario without using deadly force. In fact, it’s doubtful that an officer could draw his weapon and squeeze off a round, without aiming, if a suspect began his charge from a distance of twenty-one feet or less. Suppose the officer did properly assess the threat and did manage to draw his weapon and fire. How long would it take to think about and perform those two basic tasks?

The fastest officer tested was able to draw his weapon from a security holster in a little under 1.5 seconds. The slowest was a about 2.25 seconds. Sounds pretty fast, huh? Maybe not.

The average suspect can cover the distance (21 feet as seen above) from a standing still position to the officer in as little as 1.5 seconds, nearly a full second quicker than the slowest officer is able to defend himself.

Today officers must rethink the twenty-one foot rule a bit. Sure, the thug is potentially a deadly threat, but not an actual deadly threat until he makes some sort of hostile movement toward the officer. Of course the officer should have his firearm in a ready position as soon as he perceives the threat. And this is a situation where the officer should always choose his firearm over a non-lethal weapon, such as a Taser or pepperspray. Remember the the old saying, “Never bring a knife to a gunfight?” Now there’s a new addition to that rule. It’s, “Never bring a Taser to a knife fight.”

The key to knowing when it’s time to shoot is simple. If the officer feels that his life, or the life of an innocent person, is at risk, then the shoot is justified. However, the officer must be prepared to articulate his reasons for pulling the trigger. Was the suspect making stabbing motions while advancing? Was he charging the officer?

There are reasons that may not justify the shoot, such as the suspect being so intoxicated that he couldn’t possibly have followed through with the threat. In short, the threat must be real, or at least perceived as being real in the eyes of the officer.

And, the officer must be able to recognize when a threat is over. If the suspect drops his weapon the justification for deadly force ends immediately. The same is true when a suspect uses an automobile as a weapon. When a driver uses his car to charge an officer, the officer may shoot to stop the threat. However, when the car passes the officer the threat is over. The officer may not shoot at the fleeing car. Where would those rounds go? Besides, bullets won’t stop a moving car. Suppose the driver is shot? What happens to a driverless car that’s careening down a busy street at 40mph?

When a suspect points a firearm at an officer, deadly force is immediately justified.

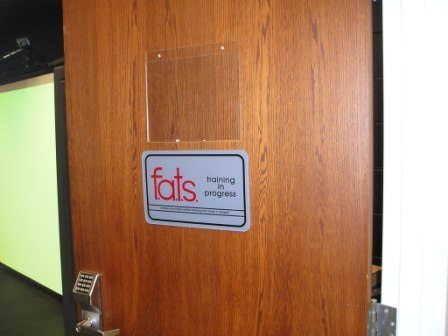

In situations like the one pictured above, it’s not uncommon for officers to hesitate briefly before using force to stop the threat. Why? Interestingly, officers often perceive women and children as being less of a threat than a male suspect. That’s why FATS and other simulated firearms training uses both women and children in the shoot/don’t shoot scenarios. The woman in the picture above is very much a deadly threat; therefore, the officer is justified in using deadly force.

Let’s see how well you do with a short true or false quiz. The answers are posted at the end of the quiz.

True or False

1. There are constitutional limits on the types of weapons and tactics officers can use on the street.

2. An officer’s intent and state of mind at the time she used force can be an important factor in determining if that use of force was legal.

3. An officer must always retreat before using deadly force.

4. Officers MUST see a suspect’s weapon before using deadly force.

5. Officers must always use the least amount of force possible to gain control of a suspect.

6. Officers may shoot a fleeing felon.

7. Officers may not use force when conducting a pat down (Terry stop) search for weapons.

8. Information discovered after using force can be a factor in determining the legality of the force used.

9. Courts and juries are allowed to evaluate an officer’s use of force by considering what the officer could have done differently.

10. An officer’s prior use of force incidents can be considered in court when evaluating whether the use of force in a current situation was legally justified.

Quiz Source – Circuit Court Judge Emory Pitt, Jr. and Americans for Effective Law Enforcement

Answers 1F, 2F, 3F, 4F, 5F, 6T, 7F, 8F, 9F, 10F

Show me your hands!

Drop the gun!

Drop the knife!

Get out of the car, now!

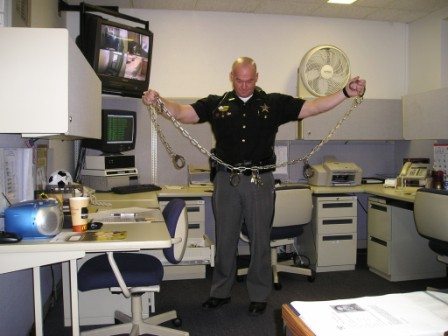

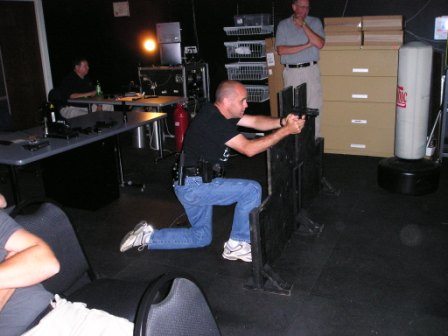

The scenes were intense as experienced police officers from the Triad area of North Carolina gathered together to stop scores of gun and knife-wielding bad guys. The officers were forced to use whatever cover they could find during a few pretty chilling shootouts. In one instance, a deputy sheriff was shot by two armed suspects and the lone backup officer was forced to shoot it out with the desperate cop killers.

Later, crazed gunmen entered a high school and began shooting random victims. Three officers entered the school and confronted the shooters. The actions of those officers saved the lives of numerous teenagers.

Actually, the lives of many innocent people were spared during this day-long mandatory training, because officers faced with several potentially deadly scenarios showed incredible skills, knowledge, and restraint. And that’s what FATS training is designed to do, to teach officers when, and when not, to use deadly force.

All police officers are required to attend regular in-service training to maintain their certification as officers. Last Thursday, I attended officer in-service training at the public safety building on the campus of Guilford Technical Community College (GTCC). The training consisted of several classes, but I specifically focused on the Firearms Training Simulator (FATS), since that’s one of the workshops we’re offering at the Writers’ Police Academy (WPA), in September. In fact, the WPA is going to be held at GTCC, and this was the actual room and equipment we’ll be using.

So, come on in, load your weapons, and prepare for the worst.

During the WPA FATS training, attendees will be assigned a partner and together you’ll be expected to do what it takes to end each of the highly charged scenarios. Suspects may or may not comply with your commands. It’s up to you and your partner to see that they do. Remember, the bad guys are criminals and will do what it takes to escape. Many of them are armed, and some of them will shoot at you!

A suspect fires at the responding officer.

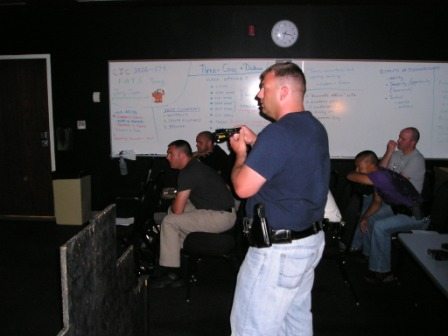

FATS Instructor Jerry Cooper

The Writers’ Police Academy FATS class will be taught by certified instructor Jerry Cooper. Remember, the Writers’ Police Academy is a realistic police academy experience designed to give writers an inside look at actual police training. This is not a typical writers conference.

We will be using real Sig Sauers and Glocks for the FATS training. The weapons have been modified for use with the FATS system. We’ll also be utilizing pepperspray and flashlights (night scenarios) that have been specially designed to work with FATS.

Officers are constantly reminded of their use of force options, even during the live training scenarios.

An officer’s chance of survival during a firefight is 95% if he uses some sort of cover.

When the threat level de-escalates, so must an officer’s level of force. For example, officers may not shoot a fleeing felon. The threat diminished when the suspect chose to run. Instructor Jerry Cooper reminds officers to use non-lethal weapons when appropriate. In this instance, he’s indicating an expandable baton.

A good old-fashioned knee strike may be all that’s needed to bring a combative suspect under control.

Officers are cautioned about sympathetic gun fire—when one officer fires, everyone shoots as a reaction.

A suspect dropped his gun, but was still non-compliant and extremely combative. This officer holstered his firearm and switched to the non-lethal Taser, an appropriate move.

FATS training is realistic and can be very intense, but it’s also a lot of fun. It is our hope that each attendee of the Writer’s Police Academy will leave the event with a better understanding of what it’s like to spend the day as a police officer. This event is designed to make you a part of the law enforcement world, even if it’s only for a weekend. There’s no other experience like this, anywhere. It’s like Disneyland for writers. See you there!

September 24-26, 2010

Guilford Technical Community College

Jamestown, N.C.

* Don’t forget to stop by our Facebook page for a peek at the author of the day. It could be you!

Countdown to 2024 KILLER CON

Writers’ Police Academy

The 2024 Writers’ Police Academy is a special event called Killer Con, which is designed to help writers create stunning realism in their work, Killer Con focuses on the intricate details surrounding the crime of murder and subsequent investigations.

Visit The WPA website to register!

*The Writers’ Police Academy (WPA) is held every year and offers an exciting and heart-pounding interactive and educational hands-on experience for writers to enhance their understanding of all aspects of law enforcement, firefighting, EMS, and forensics.

Get to Know Lee Lofland

Lee Lofland is a nationally acclaimed expert on police procedure and crime-scene investigation, and is a popular conference, workshop, and motivational speaker.

Lee has consulted for many bestselling authors, television and film writers, and for online magazines. Lee has appeared as an expert on national television, BBC Television, and radio shows.

Lee is the host and founder of the Writers’ Police Academy, an exciting, one-of-a-kind, hands-on event where writers, readers, and fans learn and train at an actual police academy.

To schedule Lee for your event, contact him at lofland32@msn.com