Obstruction of Justice (aka perverting the course of justice) is a broad term that simply boils down to charging an individual for knowingly lying to law enforcement in order to change to course/outcome of a case, or lying to protect another person. The charge may also be brought against the person who destroys, hides, or alters evidence.

Penalties for obstruction of justice vary from state to state, and the federal government. For example, in Virginia, Obstruction of Justice is a class 1 misdemeanor that carries a penalty of up to one year in jail.

Misdemeanor Classes in Virginia

§ 18.2-11. Punishment for conviction of a misdemeanor.

The authorized punishments for conviction of a misdemeanor are:

(a) For Class 1 misdemeanors, confinement in jail for not more than twelve months and a fine of not more than $2,500, either or both.

(b) For Class 2 misdemeanors, confinement in jail for not more than six months and a fine of not more than $1,000, either or both.

(c) For Class 3 misdemeanors, a fine of not more than $500.

(d) For Class 4 misdemeanors, a fine of not more than $250.

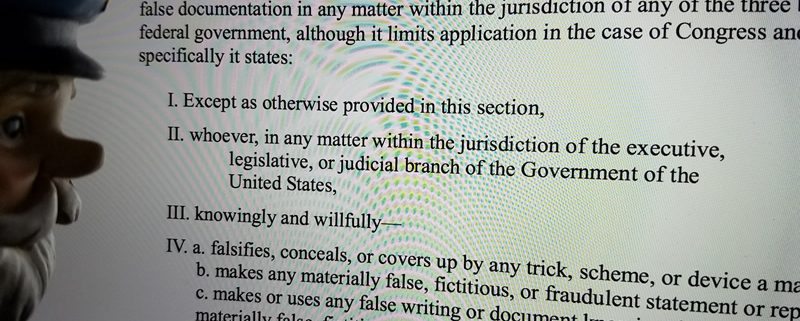

The federal government sees the crime of obstruction in a different light. In their eyes, obstruction is a felony that carries a stiff penalty. For example, in 2010, a Georgia deputy sheriff, Mitnee Jones, was convicted of Obstruction for lying to the FBI and providing false statements as part of an investigation into the death of a Fulton County jail inmate.

The jury convicted Jones of filing a false incident report with the intent to hinder the federal investigation, making a false material statement about the incident to a Special Agent of the FBI, and obstruction of justice by making false statements to a federal grand jury investigating the death of the inmate.

Jones faced a maximum prison sentence of 20 years for filing the false incident report with the intent to hinder the federal investigation; five years for making a false material statement about the incident to the FBI, and 10 years for obstruction of justice by making false statements to a federal grand jury. However, at sentencing, Jones received a much lighter sentence of one year and three months in prison to be followed by three years of supervised release. She was also ordered to perform 120 hours of community service.

Not all obstruction of justice cases are simple, with paper trails to follow. Remember Martha Stewart? The government’s criminal case against Stewart was based solely on the fact that she made false and misleading statements to the SEC, and those accusations led to Stewart’s conviction for obstruction of justice, and the charge of lying to federal investigators.

By the way, the feds love to add obstruction charges to their cases (every suspect lies to the police at some point, right?).

They do so because the threat of the additional 5-year sentence for obstruction is a great bargaining tool when offering a plea deal (We’ll drop the obstruction charge if you plead guilty to possession of the cocaine).

Here’s the obstruction section from the Code of Virginia:

Obstruction of Justice – Code of Virginia

§ 18.2-460. Obstructing justice; penalty.

A. If any person without just cause knowingly obstructs a judge, magistrate, justice, juror, attorney for the Commonwealth, witness, any law-enforcement officer, or animal control officer employed pursuant to § 3.2-6555 in the performance of his duties as such or fails or refuses without just cause to cease such obstruction when requested to do so by such judge, magistrate, justice, juror, attorney for the Commonwealth, witness, law-enforcement officer, or animal control officer employed pursuant to § 3.2-6555, he shall be guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor.

B. Except as provided in subsection C, any person who, by threats or force, knowingly attempts to intimidate or impede a judge, magistrate, justice, juror, attorney for the Commonwealth, witness, any law-enforcement officer, or an animal control officer employed pursuant to § 3.2-6555 lawfully engaged in his duties as such, or to obstruct or impede the administration of justice in any court, is guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor.

C. If any person by threats of bodily harm or force knowingly attempts to intimidate or impede a judge, magistrate, justice, juror, attorney for the Commonwealth, witness, any law-enforcement officer, lawfully engaged in the discharge of his duty, or to obstruct or impede the administration of justice in any court relating to a violation of or conspiracy to violate § 18.2-248 or subdivision (a) (3), (b) or (c) of § 18.2-248.1, or § 18.2-46.2 or § 18.2-46.3, or relating to the violation of or conspiracy to violate any violent felony offense listed in subsection C of § 17.1-805, he shall be guilty of a Class 5 felony.

D. Any person who knowingly and willfully makes any materially false statement or representation to a law-enforcement officer or an animal control officer employed pursuant to § 3.2-6555 who is in the course of conducting an investigation of a crime by another is guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor.

* Not everyone who lies to local and state police is charged with obstruction. If so, nearly every person who’s been questioned by officers would be in jail, because, based on my experiences, approximately 9 out of 10 suspects lie when they’re in the “hot seat.”

When it comes to charging someone with obstruction, well, you’ve got to carefully pick your battles, and then fight them wisely.