Writers need to know that procedures vary across the country. California, for example, is practically a world of its own and definitely beats a different drum than the rest of the country. I know because we lived there for well over a decade. I’m also quite familiar with how things go in other parts of the country, such as Virginia and North Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin, and more.

No two states are identical—laws, rules, and regulations vary from place to place. In fact, procedures, guidelines, governance, and even local ordinances differ. No two law enforcement agencies operate in precisely the same manner. Their differences may be slight, to great.

The takeaway is this—if your story is set in an actual town, city, or county, please research those specific areas, especially if your goal is realism.

No, Medical Examiners Don’t Always Show Up at Murder Scenes

In some locations, typically rural, medical examiners may not respond to homicide scenes, or suspected homicide scenes. Instead, as is the case of many areas within in the Commonwealth of Virginia, EMS or a funeral home is responsible for transporting the body to a local hospital where a doctor or local M.E. examines the victim. I’ve investigated numerous homicides where the medical examiner opted to not respond to the scene of the crime.

If a suspicious death occurs during the nighttime hours, the exam may not occur until the next day when the M.E. returns to work after a good night’s sleep. And, in those rural locations, if an autopsy is to be performed it is not the local medical examiner who’d conduct it. Instead, the body is transported to a state morgue which could be located hours away.

In Virginia, there are only four state morgue locations/district offices (Manassas, Norfolk, Richmond, and Roanoke) where autopsies are conducted. Each of the district offices is staffed by forensic pathologists, investigators, and various morgue personnel.

Breaking Bread with Kay Scarpetta

The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) is located in Richmond (the office where Patricia Cornwell’s fictional M.E., Kay Scarpetta, worked). This is also the M.E.’s office responsible for conducting the autopsies on the homicide cases I investigated. The real-life Kay Scarpetta was our M.E., and she is brilliant.

She, in fact, and one of her assistants, joined Denene and me at dinner at the Commonwealth Club in Richmond the night Denene received her PhD in pathology from Virginia Commonwealth University. Ironically, it was this very assistant to the real-life Kay Scarpetta who months later performed the autopsy on a bank robber who engaged me in a shootout. And it was she who, in explicit detail, informed me that four of the five rounds I’d fired into the center of the robber’s chest were fatal rounds. The fifth, she told me, entered the skull at an angle that would not have resulted in death.

There are several local M.E.’s in Virginia (somewhere around 160, or so) but they do not conduct autopsies. Their job is to assist the state M.E. by conducting field investigations, if they see fit to do so, but many do not. Mostly, they have a look at the bodies brought to hospitals by EMS, sign death certificates, and determine whether or not the case should be referred to the state M.E.’s office for autopsy. They definitely do not go to all death scenes. Again, some do, but not all.

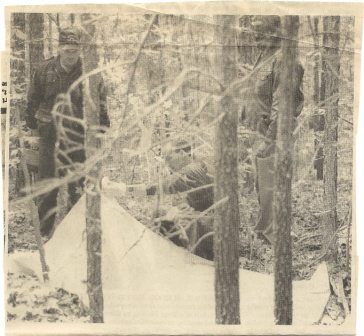

An example (one of many) was a drug-related execution in a county near where I worked as a city police detective. The sheriff of the county contacted my chief and requested that I assist in the investigation. Following the evidence, I and the sheriff’s investigators located the killers and after interrogating one of the suspects, he led me to the crime scene where we found the deceased victim. The suspects shot and killed the victim and then carried and dragged the body several yards, deep into a wooded area.

The men, after tiring of dragging the dead weight, left the body between a few small trees, in a thicket of briars and poison oak. Insects—beetles, flies, etc.—had begun their feasts. Scores of ants marched in lines across the body and in and out of the mouth, nose, and ears. A wasp crawled from inside the mouth and stood at the tip of the man’s tongue while stretching its wings. Hundreds of mosquitos swarmed around us and punctured our exposed flesh at will. They were relentless, and each of us had to return to our various cars to retrieve whatever protective clothing we could find.

The local medical examiner was spared of the mosquito bites and poison oak allergies because he chose to not respond to the scene. Instead, he settled for our statements, photos, and my video recording. He requested that the body be delivered to a local hospital. EMS placed the remains into a body body bag, sealed it, and then headed off to the morgue with a deputy sheriff tagging along for the ride to ensure the chain of custody was not broken.

Me standing on the left at a murder scene where a drug dealer was executed by rival gang members who then hid the body in a wooded area. I was asked to assist a sheriff’s office with the investigation. The medical examiner was called but elected to not go to the scene. The body and sheet used by the suspects to drag the victim were placed into a body bag and then transported to the morgue via EMS ambulance.

Pursuant to § 32.1-283 of the Code of Virginia, all of the following deaths are investigated by the OCME:

- any death from trauma, injury, violence, or poisoning attributable to accident, suicide or homicide;

- sudden deaths to persons in apparent good health or deaths unattended by a physician;

- deaths of persons in jail, prison, or another correctional institution, or in police custody (this includes deaths from legal intervention);

- deaths of persons receiving services in a state hospital or training center operated by the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services;

- the sudden death of any infant; and

- any other suspicious, unusual, or unnatural death.

* Remember, “investigated” does not mean they have to go to the actual crime scene.

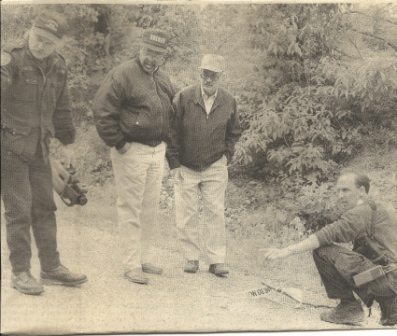

Again, me on the left as a sheriff’s office crime scene investigator points out the location of spent bullet casings, drag marks, and a blood trail. Pictured in the center are a county sheriff and prosecutor. The M.E. elected to not travel to the scene. As good luck would have it, we had the killers in custody at the conclusion of a nonstop, no sleep, 36-hour investigation.

After a lengthy interrogation, two of the four confessed to the murder. Of course, they each pointed to someone else as the shooter, and he, the actual shooter, placed the blame on his partners. But all four admitted to being present when the murder occurred and all four served time for the killing.

In the areas far outside the immediate area of Virginia’s four district offices of the chief medical examiner, where officials rely on local, part-time medical examiners, it is typically police detectives/officers who determine when a body can be removed from the scene. EMS, after checking for signs of life, stand by until the police instruct them to transport the body.

If the local M.E. shows up, and they’re almost always called, he/she will have a say in when the body is to be removed, but it’s rare that they do anything other than gather information for their notes and discuss possibilities and evidence with the police investigators.

Take Two Bodies and Call Me in the Morning!

In many cases, the local M.E.’s will simply instruct the calling detective to have EMS transport the body to the hospital morgue where they’ll take a look when they have a chance. They’ll sometimes ask to speak to the EMS person in charge of their crew to verify that the victim is indeed, well, dead.

The pay for local M.E’s in Virginia is a “whopping” $150 per case. Local M.E.s receive an extra $50 if they actually go to a crime scene. Again, many do not. Interestingly, funeral homes pay the local medical examiner $50 for each cremation he or she certifies.

Local medical examiners in Virginia also provide cremation authorizations for funeral homes and crematories. Cremation authorizations are required for cremation of anyone who died in Virginia. Funeral homes performing cremations must pay the local medical examiner $50 for each authorization.

The requirements to become a local M.E. in Virginia are:

- A valid Virginia license as a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, Nurse Practitioner, or Physician Assistant

- An appointment by Virginia’s chief medical examiner

- A valid United States driver’s license

Once someone is appointed as a local medical examiner their term is for three years, beginning on October 1 of the year of appointment.

The four district offices employ full-time forensic pathologists who conduct all autopsies. Obviously, a physician’s assistant is not qualified to conduct an autopsy, nor are they trained as police/homicide investigators.

Remember, things are never the same/uniform across the country. It’s always best, if you’re going for 100% realism, to check with someone in the area where your story is set. The rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

For example, in one Ohio county, a coroner there mandated that autopsies be performed for all deaths that occurred during vehicle crashes. This is not so in other areas of the country, or even in other locations in Ohio. By the way, at the time, the Ohio coroner’s office received $1,500 per autopsy performed, with $750 of the sum going to the pathologist performing the exam.