Convicted serial killer, Timothy Spencer, the Southside Strangler, appealed his death sentence. He claimed that he was factually innocent, scientists did not adequately perform the DNA testing in his case, and that DNA testing is a flawed science. Were Spencer’s claims wrong? Is DNA testing flawed?

Spencer also challenged the facility that performed the DNA testing. The court found no flaws in their procedures.

Landmark Case – 1st Death Sentence in the U.S. Based on DNA Evidence

Since so many writers craft stories involving serial killers and other murderers, I thought you would perhaps be interested in seeing a small part of the process involved in those cases as they make their way through the legal system.

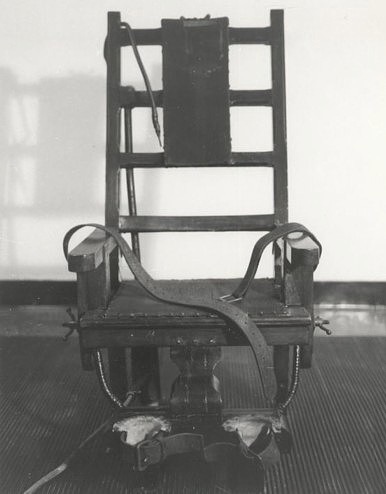

* Spencer was the first person in the U.S. sentenced to death based on DNA evidence. This was a landmark case in the United States. I served as a witness to Spencer’s execution via electric chair. Patricia Cornwell’s first book, Post Mortem, was based on Spencer’s case and of the police investigation.

The following paragraphs are excerpts from Timothy W. Spencer’s appeal to The United States Court of Appeals, 4th Circuit. His argument – The DNA testing was flawed.

*WARNING – Parts of the text are quite graphic*

5 F.3d 758

Timothy W. SPENCER, Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Edward W. MURRAY, Director, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 92-4006.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fourth Circuit.

Argued Oct. 28, 1992.

Decided Sept. 16, 1993.

J. Lloyd Snook, III, Snook & Haughey, Charlottesville, VA, argued (William T. Linka, Boatwright & Linka, Richmond, VA, on brief), for petitioner-appellant.

Donald Richard Curry, Sr. Asst. Atty. Gen., Richmond, VA (Mary Sue Terry, Atty. Gen. of Virginia, on brief), for respondent-appellee.

Before WIDENER, PHILLIPS, and WILLIAMS, Circuit Judges.

OPINION

WIDENER, Circuit Judge:

1 – Timothy Wilson Spencer attacks a Virginia state court judgment sentencing him to death for the murder of Debbie Dudley Davis. We affirm.

2 – The gruesome details of the murder of Debbie Davis can be found in the Supreme Court of Virginia’s opinion on direct review, Spencer v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 295, 384 S.E.2d 785 (1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1093, 110 S.Ct. 1171, 107 L.Ed.2d 1073 (1990). For our purposes, a brief recitation will suffice. Miss Davis was murdered sometime between 9:00 p.m. on September 18, 1987 and 9:30 a.m. on September 19, 1987. The victim’s body was found on her bed by officers of the Richmond Bureau of Police. She had been strangled by the use of a sock and vacuum cleaner hose, which had been assembled into what the Virginia Court called a ligature and ratchet-type device. The medical examiner determined that the ligature had been twisted two or three times, and the cause of death was ligature strangulation. The pressure exerted was so great that, in addition to cutting into Miss Davis’s neck muscles, larynx, and voice box, it had caused blood congestion in her head and a hemorrhage in one of her eyes. In addition her nose and mouth were bruised. Miss Davis’s hands were bound by the use of shoestrings, which were attached to the ligature device. 384 S.E.2d at 789.

3 – Semen stains were found on the victim’s bedclothes. The presence of spermatozoa also was found when rectal and vaginal swabs of the victim were taken. In addition, when the victim’s pubic hair was combed, two hairs were recovered that did not belong to the victim. 384 S.E.2d at 789. The two hairs later were determined through forensic analysis to be “consistent with” Spencer’s underarm hair. 384 S.E.2d at 789. Further forensic analysis was completed on the semen stains on the victim’s bedclothes. The analysis revealed that the stains had been deposited by a secretor whose blood characteristics matched a group comprised of approximately thirteen percent of the population. Spencer’s blood and saliva samples revealed that he is a member of that group. 384 S.E.2d at 789.

4 – Next, a sample of Spencer’s blood and the semen collected from the bedclothes were subjected to DNA analysis. The results of the DNA analysis, performed by Lifecodes Corporation, a private laboratory, established that the DNA molecules extracted from Spencer’s blood matched the DNA molecules extracted from the semen stains. Spencer is a black male, and the evidence adduced at trial showed that the statistical likelihood of finding duplication of Spencer’s particular DNA pattern in the population of members of the black race who live in North America is one in 705,000,000 (seven hundred five million). In addition, the evidence also showed that the number of black males living in North America was approximately 10,000,000 (ten million). 384 S.E.2d at 790.

5 – On September 22, 1988 a Richmond jury found Spencer guilty of rape, burglary, and capital murder. The jury unanimously fixed Spencer’s punishment at death, which was affirmed on direct appeal. Spencer then filed a petition for habeas corpus with the state trial court, which was dismissed. He appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court, but because his appeal was filed one day out of time, the Virginia Supreme Court refused the petition. Spencer then filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus with the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The district court denied his petition. Spencer v. Murray, No. 3:91CV00391 (E.D.Va. April 30, 1992).

6 – On appeal, Spencer raises essentially five issues1: (1) the DNA evidence in this case is unreliable; (2) defense counsel was denied an opportunity to adequately defend against the DNA evidence because the trial court denied a discovery request for Lifecodes’ worknotes and memoranda, the trial court refused to provide funds for an expert defense witness,2 and the prosecution did not reveal evidence of problems with Lifecodes’ testing methods; (3) the trial court should not have admitted the DNA evidence; (4) the prosecution improperly struck Miss Chrita Shelton from the jury for racially-motivated reasons as prohibited by Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986); and (5) the future dangerousness aggravating factor in Virginia’s capital sentencing scheme is unconstitutionally vague.

* Spencer’s major attack was on the DNA testing. I’ve inserted photos of the same type DNA testing (electrophoresis, or gel testing) that Spencer claimed was faulty. These photos are mine—I was the photographer. These were not part of the appeal.

Spencer’s argument boils down to an assertion that the DNA results were flawed and he was wrongly convicted. This is a claim of factual innocence. The errors he points to–potential errors in the results of the DNA test–are errors of fact, not law.

… Specifically, Spencer points to a laundry list of problems that might have occurred with his DNA test, including:

1 – Bandshifting that may have occurred because the tests were not run on same gel (list continues below images);

DNA testing by electrophoresis (gel testing) … the process

Weighing the agar gel.

Mixing the gel with water.

Gel in chamber.

Injecting DNA into the gel.

Attaching electrodes to the chamber.

Introducing electric current to the gel.

Completed gel is placed onto an illuminator for viewing.

Gel on illuminator.

*My thanks to Dr. Stephanie Smith for allowing me to hang out in her lab to take the above photos.

Completed gel showing DNA bands

DNA bands

Spencer’s claims against DNA continue:

2 – Cross-contamination or bacterial contamination of the samples because Lifecodes’ procedures do not guard against these threats;

3 – Invalidity because of the lack of data on the reliability of DNA testing of degraded forensic samples;

4 – Incorrect matching because visual inspection, rather than computer calculations, were used to declare a match;

5 – Invalidity that may have resulted from potentially poor quality control or proficiency standards;

6 – Impossibility of verifying results because Lifecodes did not record what voltage they applied to gel;

7 – Inability to know whether Lifecodes properly performed tests because there are no standards for licensure or required tests that labs must complete;

8 – Improper testimony at trial about the statistical likelihood of finding someone else with same DNA type because of potentially improper application of the product rule;

9 – Lack of validation studies to prove reliability of DNA testing in forensic setting and of using sperm to DNA type; and

10 – Possible inaccuracies resulting from Lifecodes’ use of certain probes

Spencer repeatedly urged, in his brief and at oral argument, that the main reason the DNA evidence in this case was found to be admissible is because it was “too new” to have been criticized, because the criticisms were published after his trial, and because Spencer was, according to counsel, the first person ever convicted and sentenced to death, using DNA evidence, in Virginia.

The Virginia State Supreme Court ruled that the DNA testing had been performed properly and denied Spencer’s appeal.

I sat twenty-feet or so from Spencer as he was put to death in Virginia’s electric chair. The procedure was gruesome, to say the least.

I sat twenty-feet or so from Spencer as he was put to death in Virginia’s electric chair. The procedure was gruesome, to say the least.

A few minutes after the final burst of electricity surged through Spencer’s body, time to allow the body to cool enough to allow a physical examination, the attending physician checked for signs of life. After a moment or two he looked up from Spencer’s body and said to the warden, “This man has expired.”

It was over.

Later, an unmarked DOC van carrying Spencer’s body departed the prison, passing through a crowd of people lining the roadway outside the main gate—protesters, and the many officers from state and county agencies who were assigned to maintain peace between the pro and anti death penalty groups. Both groups went silent as the van exited the prison gates and passed by on its way to the state morgue in Richmond where an autopsy was scheduled to be performed.

I knew how it felt to stand there watching those vans pass because I’d been assigned to the protection detail several times in the past. One of those times was for the execution of Roger Keith Coleman, a man convicted and sentenced to death for the rape, murder, and beheading of his sister-in-law.

Tension was high the night of Coleman’s execution and the crowds on both sides of the death penalty debate were large and angry.

Coleman’s case drew international attention. He, a coal miner from the mountains of Virginia, pleaded his case on talk shows and in magazines and newspapers. He was even featured on the cover of Time magazine. Pope John Paul II attempted to intervene, pleading to block the execution, and thousands upon thousands of protestors from around the globe sent letters to the governor of Va. Many made phone calls to his office.

But, DNA tests proved that Coleman was indeed the perpetrator of his sister-in-law’s brutal rape and murder. He submitted to a polygraph on the day of his execution as a last attempt to prove that he’d not committed the horrible crime. He failed the test.

Coleman’s final meal was a dinner of pepperoni pizza, fudge cookies, and a 7-Up. He went to “the chair” still proclaiming his innocence.

After Spencer’s execution concluded, prison officials drove me out and away from the facilty to my unmarked car I’d earlier parked behind the state police area headquarters. They’d picked me up there and driven me to the prison to prevent onlookers from knowing that I was to be a witness, a standard procedure.

As the prison van containing Spencer’s body passed by the protesters, I was already on my way home.