Location, Location, Location: Are You Writing it Wrong?

Did you know that not all sheriff’s deputies are police officers? How about that some sheriffs in the U.S., and their deputies, do not have any arrest authority? Is it possible that you, as writers, haven written scenes incorrectly based on not knowing the above facts? Well, there’s a super easy solution to fixing this lack of basic knowledge … Do Your Homework!

It takes a minimal amount of effort to check the policies, procedures, laws, and rules and regulations in the area where your story takes place. Of course, if your town is fictional then you’re the law-maker in charge. But if the setting of your latest tale is Doodlebop, Alaska, then you should conduct a bit of research to learn how things operate in Doodlebop’s town limits and surrounding areas. After all, what happens in Doodlebop, Alaska is most likely quite a bit different than the goings-on in Rinktytink, Vermont.

For example:

1. Use caution when writing cop slang. What you hear on TV may not be the language used by real police officers. And, what is proper terminology and/or slang in one area may be totally unheard of in another.  A great example are the slang terms Vic (Victim), Wit (Witness), and Perp (Perpetrator). These shortened words are NOT universally spoken by all cops. In fact, I think I’m fairly safe in saying the use of these is not typical across the U.S. Even the slang for carbonated beverages varies from place to place (soda, pop, soda pop, Coke, drink, etc.).

A great example are the slang terms Vic (Victim), Wit (Witness), and Perp (Perpetrator). These shortened words are NOT universally spoken by all cops. In fact, I think I’m fairly safe in saying the use of these is not typical across the U.S. Even the slang for carbonated beverages varies from place to place (soda, pop, soda pop, Coke, drink, etc.).

2. Simply because a law enforcement officer wears a shiny star-shaped badge and drives a car bearing a “Sheriff” logo does not mean they are all “sheriffs.” Please, please, please stop writing this in your stories. A sheriff is an elected official who is in charge of the department, and there’s only one per sheriff’s office. The head honcho. The Boss. All others working there are appointed by the sheriff to assist him/her with their duties. Those appointees are called DEPUTY SHERIFFS. Therefore, unless the boss himself shows up at your door to serve you with a jury summons, which is highly unlikely unless you live in a county populated by only three residents, two dogs, and a mule, the LEO’s you see driving around your county are deputies.

3. The rogue detective who’s pulled from a case yet sets out on his own to solve it anyway. I know, it sounds cool, but it’s highly unlikely that an already overworked detective would drop all other cases (and there are many) to embark on some bizarre quest to take down Mr. Big. Believe me, most investigators would gladly lighten their case loads by one, or more. Besides, to disobey orders from a superior officer is an excellent means of landing a fun assignment (back in uniform on the graveyard shift ) directing traffic at the intersection of Dumbass and Mistake.

4.  Those of you who’ve written scenes where a cocky FBI agent speeds into town to tell the local chief or sheriff to step aside because she’s taking over the murder case du jour…well, get out the bottle of white-out because it doesn’t happen. The same for those scenes where the FBI agent forces the sheriff out of his office so she can set up shop. No. No. And No. The agent would quickly find herself being escorted back to her guvment vehicle.

Those of you who’ve written scenes where a cocky FBI agent speeds into town to tell the local chief or sheriff to step aside because she’s taking over the murder case du jour…well, get out the bottle of white-out because it doesn’t happen. The same for those scenes where the FBI agent forces the sheriff out of his office so she can set up shop. No. No. And No. The agent would quickly find herself being escorted back to her guvment vehicle.

The FBI does not investigate local murder cases. I’ll say that again. The FBI does not investigate local murder cases. And, in case you misunderstood … the FBI does not investigate local murder cases. Nor do they have the authority to order a sheriff or chief out of their offices. Yeah, right … that would happen in real life (in case you can’t see me right now I’m giving a big roll of my eyes).

Believable Make-Believe

Okay, I understand you’re writing fiction, which means you get to make up stuff. And that’s cool. However, the stuff you make up must be believable. Not necessarily fact, just believable. Write it so your readers can suspend reality, even if only for a few pages. Your fans want to trust you, and they’ll go out of their way to give you the benefit of the doubt. Really, they will. But for goodness sake, give them something to work with,—without an info dump—a reason to believe/understand what they’ve just seen on your pages. A tiny morsel of believability goes a long way.

Saying This Again

If you’re going for realism, and I cannot stress this enough, please do your homework. Remember, no two agencies operate in exactly the same manner, nor are rules and even many laws/ordinances the same in states, towns, counties, and cities. Actually, things are never the same/uniform across the country. Therefore, it’s always best to check with someone in the area where your story is set. Again, rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

For example, there are 3,081 sheriffs in the U.S., and I can say with certainty that neither of those top cops runs their office in a manner that’s identical to that of another. Each sheriff has their own set of policies, rules, and regulations, and each state has their own laws regarding sheriffs and their duties.

The same is true with other agencies, including the offices of medical examiners and coroners. State law, again, dictates whether or not they utilize a coroner system or that of a medical examiner.

*By the way, three states do not have Sheriff’s Offices—Alaska, Connecticut, and Hawaii.

Location, Location, Location!

As when writing about a sheriff’s office, if your story features a medical examiner, or coroner, you should narrow your research efforts to the area where your story takes place. Here’s why …

In some locations, typically rural, a medical examiner does not always go to the scene of a homicide. Instead, as is the case of many areas within in the Commonwealth of Virginia, EMS or a funeral home is responsible for transporting the body to a local hospital morgue where a doctor or local M.E. examines the victim. If an autopsy is to be performed, though, it is not the local medical examiner who’d conduct it. Instead, the body is transported to a state morgue which could be hours away.

In Virginia, there are only four state morgue locations/district offices (Manassas, Norfolk, Richmond, and Roanoke). Each of the district offices is staffed by forensic pathologists, investigators, and various morgue personnel, and this where autopsies are conducted, not at the local morgue/hospital.

The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) is located in Richmond (the office where Patricia Cornwell’s fictional M.E., Kay Scarpetta, worked). This is also the M.E.’s office that conducted the autopsies on the homicide cases I investigated. The real-life Kay Scarpetta was our Chief M.E.

There are several local medical examiners in Virginia (somewhere around 160, or so) but they do not conduct autopsies. Their job is to assist the state’s Chief Medical Examiner. by conducting field investigations, if they see fit to do so, but many do not. Mostly, they have a look at the bodies brought to hospitals by EMS, sign death certificates, and determine whether or not the case should be referred to the state M.E.’s office for autopsy. They definitely do not go to all death scenes. Again, some do, but not all.

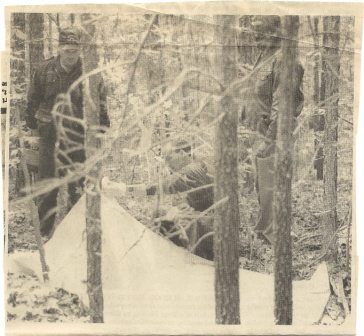

An example (one of many) was a drug-related execution where I was called on by a nearby county sheriff to assist his department in the investigation. Following the evidence, I and sheriff’s detectives located the killers. After interrogating one of the suspects he led me to the crime scene where we found the deceased victim after an exhausting search. The suspects carried and dragged the body several yards, deep into a wooded area. The local medical examiner did not attend. Instead, he requested that the body be delivered to a local hospital.

Above – Me standing on the left at a murder scene where a drug dealer was executed by rival gang members, who then hid the body in a wooded area. I was asked to assist a sheriff’s office with the investigation. The medical examiner was called but elected to not go to the scene. The body and sheet used by the suspects to drag the victim were placed into a body bag and then transported to the morgue via EMS ambulance.

Pursuant to § 32.1-283 of the Code of Virginia, all of the following deaths are investigated by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner:

- any death from trauma, injury, violence, or poisoning attributable to accident, suicide or homicide;

- sudden deaths to persons in apparent good health or deaths unattended by a physician;

- deaths of persons in jail, prison, or another correctional institution, or in police custody (this includes deaths from legal intervention);

- deaths of persons receiving services in a state hospital or training center operated by the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services;

- the sudden death of any infant; and

- any other suspicious, unusual, or unnatural death.

* Remember, “investigated” does not mean they have to go to the actual crime scene.

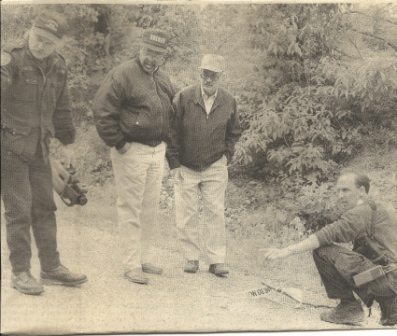

Again, me on the left as a sheriff’s office crime scene investigator points out the location of spent bullet casings, drag marks, and a blood trail. Pictured in the center are the county sheriff and prosecutor. The M.E. elected to not travel to the scene. As good luck would have it, we had the killers in custody at the conclusion of a nonstop, no sleep, 36-hour investigation.

After a lengthy interrogation, two of the four confessed to the murder. Of course, they each pointed to someone else as the shooter, and he, the actual shooter, placed the blame on his partners. But all four admitted to being present when the murder occurred and all four served time for the killing.

Take Two Bodies and Call Me in the Morning!

In the areas far outside the immediate area of Virginia’s four district offices of the chief medical examiner, officials rely on local, part-time medical examiners who may or may not visit crime scenes.

In those rural areas, once a death is confirmed, detectives call the local, part-time M.E. who typically defers to EMS to determine that the victim is indeed dead. They then advise the detectives to, once they’ve completed their on-scene investigation, have EMS bring the body to the local morgue where they’ll have a look at their earliest convenience..

Since most local M.E.s work full-time jobs they are not always readily available to visit a crime scene.

“Yeah, he’s dead, now gimme my money.”

The pay for local M.E’s in Virginia is a “whopping” $150 per case, if the case referred to the state is one that falls under their jurisdiction. The local M.E.s receive an extra $50 if they actually go to a crime scene. Again, many do not. Interestingly, funeral homes pay the local medical examiner $50 for each cremation he or she certifies.

The requirements to become a local M.E. in Virginia are:

- A valid Virginia license as a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, Nurse Practitioner, or Physician Assistant

- An appointment by Virginia’s chief medical examiner

- A valid United States driver’s license

Once someone is appointed as a local medical examiner their term is for three years, beginning on October 1 of the year of appointment.

The four district offices employ full-time forensic pathologists who conduct all autopsies. Obviously, a physician’s assistant is not qualified to conduct an autopsy, nor are they trained as police/homicide investigators. They do attend some training courses, however.

And, Again …

Keep in mind, things are never the same/uniform across the country. It’s always best, if you’re going for 100% realism, to check with someone in the area where your story is set. The rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

Keep in mind, things are never the same/uniform across the country. It’s always best, if you’re going for 100% realism, to check with someone in the area where your story is set. The rules and regulations on one side of the country may not be the same on the other. And the middle of the country may also be totally different from the other localities.

Coroners

The same inconsistencies seen in the running of sheriffs’ and medical examiners’ offices occur in individual coroner’s offices. For example, in one Ohio county, one of four coroner’s investigators respond to a scene, if they believe it’s necessary. Then, after the body is brought back to the morgue by the coroner’s team, within the next day or so, a pathologist conducts the autopsy. The same or similar is so in many, many areas of the country … or not.

Per state law, a coroner in Ohio must be an MD, but they may or may not be the person who conducts the autopsy. In the office mentioned above, autopsies were typically performed by a part-time MD/pathologist who also works at the local hospital. The same MD there now was the pathologist who conducted autopsies when I was last there. I checked today, in fact.

Pathologists in the Ohio county are paid per autopsy. At the time I was there, the office received $1,500 per autopsy, with $750 of the sum going to the pathologist performing the exam. (the sum was $750 the last time I viewed an autopsy there) with remaining $750 going to the coroner’s general operating budget. The pathologist was not a full-time employees of the coroner’s office.

Oh, yeah, there’s a difference between a coroner and a medical examiner, but that’s a topic for another article.

Fun Fact – Some California sheriffs also serve as coroners. They are not medical doctors, obviously. Coroners are elected officials and could be the local butcher, baker, or candlestick maker, as long as they won the local election.

So, from me to you, here’s your homework assignment …

DO YOUR HOMEWORK!!

Believe me, your readers will love that you’ve “gotten it right.”

Speaking of doing your homework, here’s the ultimate training event for writers …

Featuring David Baldacci – Guest of Honor

David Baldacci is a global #1 bestselling author, and one of the world’s favorite storytellers. His books are published in over 45 languages and in more than 80 countries, with over 130 million copies sold worldwide. His works have been adapted for both feature film and television. He has also published seven novels for young readers.

David is also the cofounder, along with his wife, Michelle, of the Wish You Well Foundation®, which is dedicated to supporting adult and family literacy programs in the United States.

David is a graduate of Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Virginia School of Law. He lives in Virginia.

With special guests …

Judy Melinek, M.D. was an assistant medical examiner in San Francisco for nine years, and today works as a forensic pathologist in Oakland and as CEO of PathologyExpert Inc. She and T.J. Mitchell met as undergraduates at Harvard, after which she studied medicine and practiced pathology at UCLA. Her training in forensics at the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner is the subject of their first book, the memoir Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 Bodies, and the Making of a Medical Examiner.

T.J. Mitchell is a writer with an English degree from Harvard, and worked in the film industry before becoming a full-time stay-at-home dad. He is the New York Times bestselling co-author of Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 Bodies, and the Making of a Medical Examiner with his wife, Judy Melinek.

Ray Krone is co-founder of Witness to Innocence. Before his exoneration in 2002, Ray spent more than 10 years in Arizona prisons, including nearly three years on death row, for a murder he did not commit.

His world was turned upside down in 1991, when Kim Ancona was murdered in a Phoenix bar where Ray was an occasional customer, and he was arrested for the crime. The case against him was based largely on circumstantial evidence and the testimony of a supposedly “expert” witness, later discredited, who claimed bite marks found on the victim matched Ray’s teeth. He was sentenced to death in 1992.

With a special presentation by Dr. Denene Lofland – A Microbiologist’s Perspective of Covid 19 and the Spread of Disease.

Denene Lofland is an expert on bioterrorism and microbiology. She’s managed hospital laboratories and for many years worked as a senior director at biotech companies specializing in new drug discovery. She and her team members, for example, produced successful results that included drugs prescribed to treat cystic fibrosis and bacterial pneumonia. Denene, along with other top company officials, traveled to the FDA to present those findings. As a result, those drugs were approved by the FDA and are now on the market.

Denene Lofland is an expert on bioterrorism and microbiology. She’s managed hospital laboratories and for many years worked as a senior director at biotech companies specializing in new drug discovery. She and her team members, for example, produced successful results that included drugs prescribed to treat cystic fibrosis and bacterial pneumonia. Denene, along with other top company officials, traveled to the FDA to present those findings. As a result, those drugs were approved by the FDA and are now on the market.

Calling on her vast expertise in microbiology, Denene then focused on bioterrorism. With a secret security clearance, she managed a team of scientists who worked in an undisclosed location, in a plain red-brick building that contained several laboratories. Hidden in plain sight, her work there was for the U.S. military.

She’s written numerous peer reviewed articles, contributed to and edited chapters in Bailey and Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology, a textbook used by universities and medical schools, and, as a professor, she taught microbiology to medical students at a well-known medical school. She’s currently the director of the medical diagnostics program at a major university, where she was recently interviewed for a Delaware public service announcement/video about covid-19.

Denene is a regular featured speaker at the annual Clinical Laboratory Educators Conference, and she’s part of the faculty for the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners.

She was recently named a Fellow of the Association of Clinical Scientists, an elite 200-member association of top scientists from around the world that includes pathologists, clinical chemists, molecular and cell biologists, microbiologists, immunologists, hematologists, cytogeneticists, toxicologists, pharmacokineticists, clinicians, cancer researchers and other doctoral scientists who are experts in laboratory methods for the elucidation, diagnosis, and treatment of human diseases.

Getting it right doesn’t only mean about law enforcement and procedure. I hate reading a book that is set in a real location and the author gets the information wrong. For example, a well-known author wrote a book set in Oklahoma has no cell service north of Oklahoma for 90 miles (almost to the Kansas line, by the way). Oklahoma has had cell service except in very small locations for over 20 years. The author also had a location (can’t tell where because he gives directions that contradict themselves) which is 20 miles of wheat without any road except one that leads to the “bad guy’s” compound. There is no such area in Oklahoma that is believable unless he set it in the Panhandle and added a few cross roads. So, research, even in fiction, is necessary.