Dr. Katherine Ramsland: Being Jeffrey Dahmer

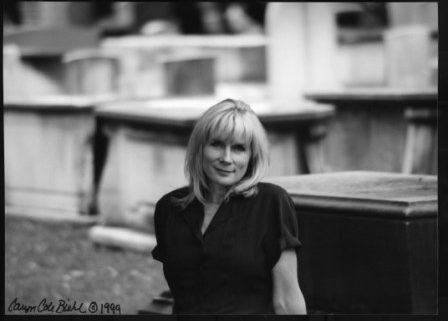

Dr. Katherine Ramsland has a master’s degree in forensic psychology from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, a master’s degree in clinical psychology from Duquesne University, and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Rutgers. She has published thirty-three books, including The CSI Effect, Inside the Minds of Serial Killers, Inside the Minds of Healthcare Serial Killers, Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers, The Human Predator: A Historical Chronology of Serial Murder and Forensic Investigation, The Criminal Mind: A Writers’ Guide to Forensic Psychology, and The Forensic Science of CSI. With former FBI profiler Gregg McCrary, she co-authored the book on his cases, The Unknown Darkness: Profiling the Predators among Us (Morrow, 2003), and with Professor James E. Starrs, A Voice for the Dead (Putnam 2005), a collection of his cases of historical exhumations and rigorous forensic investigation.

She has been translated into ten languages; published fifteen short stories and over 900 articles on serial killers, criminology, forensic science, and criminal investigation, and was a research assistant to former FBI profiler, John Douglas (Mindhunter), which became The Cases that Haunt Us (Scribner, 2000). With FBI profiler Gregg McCrary, she wrote The Unknown Darkness, and with James E. Starrs, A Voice for the Dead, about his various historic exhumations. She currently contributes editorials on forensic issues to The Philadelphia Inquirer; writes a regular feature on historical forensics for The Forensic Examiner (based on her history of Forensic science, Beating the Devil’s Game) and teaches both forensic psychology and criminal justice at DeSales University in Pennsylvania.

Her most recent books are Into the Devil’s Den, about an undercover FBI operation inside the Aryan Nations (with Dave Hall and Tym Burkey), True Stories of CSI, The Devil’s Dozen: How Cutting Edge Forensics Took Down Twelve Notorious Serial Killers, and Murder in the Lehigh Valley. In addition, she has published biographies of both Anne Rice and Dean Koontz and penned three creative nonfiction books about penetrating the world of “vampires” (Piercing the Darkness), ghost hunters (Ghost), and the funeral industry (Cemetery Stories). From these experiences, she wrote two novels, The Heat Seekers and The Blood Hunters. Currently she’s working on a book called The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds.

Being Jeffrey Dahmer

The rain outside fed an edgy mood in the intimate space at 410 W. 42nd Street on Manhattan’s Theatre Row. Here, Bill Connington starred in his one-man, one-act play, “Zombie,” adapted by him from Joyce Carol Oates’s 1995 novella. She, in turn, had adapted her work partly from the life and crimes of cannibalistic serial killer, Jeffrey Dahmer. Grim fare, to be sure, but there’s an audience for it, and I’m one of them.

I began the evening dining with Dr. Michael Stone and his lovely wife. Dr. Stone, notable for his Discovery Channel show, “Most Evil,” proved to be a wealth of information about the trends and habits of serial killers. Great stuff, unless your meal comes with tomato sauce, which his did. We then went to the play, where he was to be the post-performance commentator.

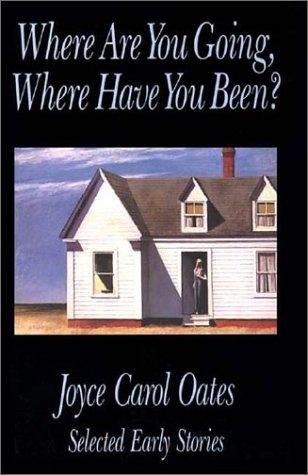

First, Zombie, the novella. Joyce Carol Oates has written that “the serial killer has come to seem the very emblem of evil” and she’s tackled the subject on several occasions. While some critics complain that Oates includes too much violence in her stories, she rightly insists that dark subjects are not the exclusive province of male writers.

During the 1960s, she penned a short story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” which was based on Charles Schmid, “the Pied Piper of Tucson.” A strange character who stuffed his cowboy boots with rags and tin cans, he still managed to charm three teenage girls into being his victims. Oates wrote from the point of view of one of one girl, as the slick killer talked his way into her house.

A psychological realist, Oates examines those urges toward violence, madness, and self-annihilation that occur during the struggle to become a fully realized self in a world that blocks our ambitions. “I feel that my own place is to dramatize the nightmares of my times,” she once told me during an interview, “and hopefully to show how some individuals find a way out.” Because her prose is so affecting, her truths unnerving, and her plots extraordinary, she compels readers to want to go where they ordinarily would not.

Another real-life inspiration was the series of mutilation murders of boys and girls in 1976 around the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, where Oates once briefly resided. Ranging in age from ten to sixteen, the victims had been abducted close to their homes and had been shot, strangled, suffocated, or bludgeoned to death. All were sexually assaulted and all were meticulously scrubbed clean. In some cases, the clothes were laundered, so the killer was dubbed “The Babysitter.” Between this series of assaults and Dahmer’s grotesque revelations in 1991, Oates found another dark character and plot.

Zombie is told from the perspective of Quentin P., a paroled sex offender who seeks to enslave a beautiful boy. He needs a zombie that will obey his every wish and fulfill his every desire, but each “experiment” ends in failure: The boys all die in some terrible manner, often while raped, but Quentin has little regard for the pain and terror they experienced. For Oates, this tale was an extended meditation on evil.

When asked what it was like to put herself so deeply into the perspective of such a deranged person as Quentin P., she said, “I was trying to do two things. One was to give voice to a person who operated on the level of instinct, who’s led by his fantasies. Quentin has impressions that are almost visceral ideas, but they’re not articulated.” Yet she was also used the character to mirror certain dehumanizing preoccupations of society, “like the lobotomies of the forties and fifties, an experiment that men performed on helpless women.

Quentin’s experiments are like this. He’s part of the culture, but the culture would say he’s a monster. His story dovetails with his father, who admired a man who’d received a Nobel Prize but who’d experimented on people. It’s no different from Quentin, but he’ll be put away if he’s caught, while the other man gets an award.”

Bill Connington, too, draws on the inner demons of a man who thinks it’s okay to subject other people to his evil needs. While so many television shows and movies feature crafty, clever, and scheming serial killers (which is far from the reality), Connington delivers an authentic sense of the bland, self-obsessed loner devising diabolical plans of abuse and torment as a harmless hobby. “This is a guy,” Connington has said, “who doesn’t realize that other people have thoughts that are separate from him. A lot of the time, he doesn’t mean to be mean, he’s just totally oblivious.” When Quentin P. fails (i.e., kills a boy rather than creating his zombie), you know it: his rage flashes hot, filling the small theater with his driving desire and unfair blame. (I was reminded of how a surviving victim of Dahmer’s testified about how Dahmer seemed to change from a goofy beer buddy into a man possessed by a demon.) Yet it’s the quiet moments during this play that are the creepiest, because in these compressed psychological spaces lie Quentin P’s true perversities. The hour-long monologue is intense, from start to finish.

Jeffrey Dahmer

When Connington sheds Quentin P. and emerges to speak to the audience, there’s a sense of collective relief that he’s not that guy at all: he’s not Jeffrey Dahmer. In fact, you can barely believe this actor is the same fiend you just saw playing solo chess and embracing his icky manikin. Connington was wise to include forensic mental health experts to answer questions, because clearly people were curious about how someone so ordinary can be so monstrous (and Michael Stone admirably discussed his work). Essentially, that’s the question that Connington answers with his deft performance: Narcissism, perverse need, isolation, and the availability of victims that a killer thinks no one will miss. That’s how such monsters get loose in the world.

Zombie runs through March 29 at the Studio Theatre, with the possibility that it will then move to a larger Manhattan venue. It appeals on many levels, but don’t eat spaghetti first.

www.katherineramsland.com/main.html

Books by Dr. Katherine Ramsland