As the result of a DNA experiment on September 10, 1984, Alec Jeffreys discovered the technique of genetic fingerprinting. At the time, Jeffreys worked as a researcher and professor of genetics at the University of Leicester.

At 9.05 a.m. that September morning, the life of Alec Jeffreys changed forever, as did the entire world of criminal investigations and paternity cases. It was, as Jeffreys calls it, his “eureka moment.”

Jeffreys’ DNA fingerprinting was first used in a police forensic test to identify the killer of two teenagers, Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth. The two young women had been raped and murdered in 1983 and 1986 respectively.

A 17-year-old boy with learning difficulties—Richard Buckland—confessed to one of the killings but not the other.

The detective in charge of the case was skeptical of Buckland’s odd confession and his involvement, or lack of, in the second murder. The detective recently learned of Alec Jeffreys’ breakthrough discovery and figured, well, he thought he had nothing to lose so he contacted the scientist to ask if he thought his new technique could prove that Buckland had murdered both young women. The top cop was in for a surprise.

Jeffreys agreed to see what he could do and extracted DNA from Buckland’s blood and from semen taken from the dead girls’ bodies. Then he compared them, immediately seeing that the girls had been raped by the same man. However, Buckland’s DNA was completely different. He had not been in contact with either of the victims.

Police had the wrong man and, after three months in jail, Buckland was released from custody.

Detectives then came up with a wild plan. They decided to set up an operation to gather the DNA of every man in the area. Eight months later, after eight months of sampling and testing, 5,511 men had given blood samples. Only one man had refused to cooperate and after testing all those samples, still no match to the semen samples collected from the victims.

Among the over 5,000 men who provided blood samples was a 27-year-old baker and father of two young children named Colin Pitchfork. Three years earlier, police had questioned him about his movements on the evening that Lynda had been murdered. But nothing came of it.

In August 1987, over a year after the killing of Dawn, one of Colin Pitchfork’s coworkers was in a local pub having drinks with friends and somehow Pitchfork’s name entered their conversation. One member of the group, a man named Kelly, admitted that he’d impersonated Pitchfork and took the blood test on his behalf. Kelly told the group that Pitchfork asked him to do this for him because he’d already taken the test for another friend who had a criminal conviction and was afraid of taking the test a second time. So Kelly agreed. Pitchfork then doctored his passport by inserting Kelly’s photograph in place of his own and then drove Kelly to the test site where he waited outside while Kelly’s blood was drawn.

A few weeks later, one of the people in the pub passed along the information to a local policeman. Kelly was arrested and he confessed to the impersonation. By the end of the work day Pitchfork was also in custody. One of the detectives who questioned the Pitchfork asked him, “Why Dawn Ashworth?”

Pitchfork nonchalantly replied, “Opportunity. She was there and I was there.”

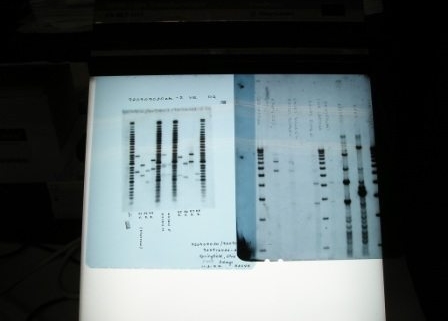

So this is how it all started. A drop of blood and a semen sample met a small electrical charge (see images of the process below). The result was a few blips on an x-ray film that resembled a grocery store product bar code. Each of us has one of those bar codes that is unique to us. And it was Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys discovered the secret to finding and reading those codes.

I knew of this incredible story and was reminded of it when Denene and I recently watched Code of a Killer, the television mini-series based on these events.

Joseph Wambaugh told the story in his 1989 best selling book The Blooding: The True Story of the Narborough Village Murders.

Finally, after watching the TV show I recommend taking a moment or two to watch Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys lecture about his discovery, and you may do so below.

DNA testing by electrophoresis (gel testing) … the process

Weighing the agar gel.

Mixing the gel with water.

Gel in chamber.

Injecting DNA into the gel.

Attaching electrodes to the chamber.

Introducing electric current to the gel.

Completed gel is placed onto an illuminator for viewing.

Gel on illuminator.

*My thanks to Dr. Stephanie Smith for allowing me to hang out in her lab to take the above photos.

Completed gel showing DNA bands

DNA bands

DNA Facts

- DNA is the acronym for deoxyribonucleic acid.

- DNA is a double-helix molecule built from four nucleotides: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C).

- Every human being shares 99.9% of their DNA with every other human.

- If you placed all the DNA molecules in your body end to end, the DNA would reach from the Earth to the Sun and back over 600 times!

- Humans share 60% of our genes with fruit flies.

- We share 98.7% of our DNA in common with chimpanzees and bonobos.

- If you could type 60 words per minute, eight hours a day, it would take approximately 50 years to type the human genome.

- Humans share 85% of our DNA with a mouse.

- We also share 41% with a banana.

- According to a study conducted at Princeton University, all humans, including Africans likely have a bit of Neanderthal in our DNA. This was a fascinating discovery since until these findings were released in 2020 it was believed that Africans did not have Neanderthal DNA.

- Friedrich Miescher discovered DNA in 1869. However, it was not until 1943 that scientists came to understand that DNA was the genetic material in cells.