Mr. X is a former business professional who committed a crime that landed him in federal prison. He’s out now and has agreed to share the story of his arrest with the readers of The Graveyard Shift. You might find this tale a bit interesting.

GYS: Thanks for taking the time to share what must have been a difficult time for you and your family. I’ll dive right in. What were the circumstances that ultimately led to your arrest?

X: It’s embarrassing to have to tell it. I’ll start by saying I was ill at the time. A mental problem, I guess you’d call it. My doctor gave me all sorts of drugs that were supposed to help me, but didn’t. They just screwed up my wiring—my thought processes. Anyway, to this day I still say I would have never done anything wrong had it not been for the assortment of antidepressants and pain pills. Still, I did what I did and I accept the responsibility for it. I wish I could change it, but I can’t.

GYS: What was the crime that ultimately led to your arrest?

X: I bought some cocaine to sell. I didn’t use the stuff, I just needed money. You see, with my mind so scrambled I couldn’t hold down a job and my wife was struggling to make ends meet. The medicine and depression simply wouldn’t let me think properly. Either I’d get fired or I’d quit for some crazy, unjustified reason. All I had on my mind was the feeling those little pills offered, especially the pain pills. At the time, I think I’d have married a bottle of Hydrocodone. I loved and craved it that much. Still do, actually, and I haven’t touched the stuff in many years. But I think about it nearly every day.

GYS: How long did your life of crime last?

X: I didn’t make a very good criminal. My entire crime spree lasted about a week. I bought the cocaine to sell, but chickened out. I couldn’t sell it. But someone who was involved in the transaction was already in trouble with the police and told them about me to help themselves out of their own jam.

GYS: Tell us about the arrest.

X: As it turns out, the person who told on me was an informant for a federal task force so, needless to say, I was surprised when my house was raided by a team of FBI agents along with state and local police. There must have been fifteen or twenty officers involved in the raid of my home. All for a little over $100 worth of cocaine. Although, I’m sure if I’d sold it it would have netted more. The prosecutor leading this investigation was a man named James Comey. You may have heard of him.

GYS: Seriously, that’s all you had?

X: Yes, sir. $120 worth, or so. A heaping tablespoon full, maybe.

GYS: What were your charges?

X: Possession of a controlled substance (cocaine) with the intent to distribute, and obstruction of justice. The obstruction charge was later dropped. I think the feds automatically add that one to make you confess.

GYS: Why do you say that about the obstruction charge?

X: They threatened to arrest everyone in my family—my wife, kids, and mother—if I didn’t confess. And if I didn’t admit to the crime they’d let the obstruction charge stand, and that’s a minimum of a ten-year sentence. I had no choice. None whatsoever. Plus, they applied this pressure prior to my talking to an attorney, which I understand is perfectly legal. But let me again stress that I was indeed guilty. I’ve never denied it.

GYS: So what happened next?

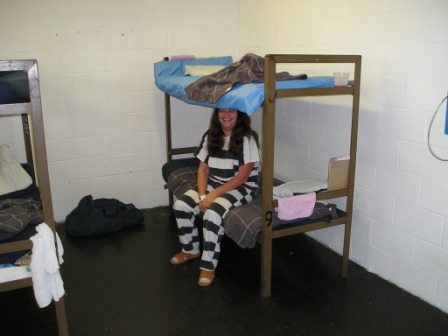

X: Gosh, it’s all a blur. Let’s see. I was handcuffed, placed in the back of a police car, driven to a remote jail hours away from my home, fingerprinted, strip searched, de-loused, and placed in a jail cell. The cell was a single cell (only one inmate) with a plastic-covered mattress atop a steel plate hanging from the wall.

A former occupant had smeared feces on the block wall in several places. The toilet didn’t flush, and the door—a solid steel door—had a family of roaches living inside the hinges and other tiny crevices. They came out to explore at various times throughout the day and night. By the way, it was difficult to distinguish between night and day because there was no window and the overhead light remained on 24/7. It was a real shock to me. I’d never even had a traffic ticket.

Oh, my family had no idea where I was, or what had happened. They were away when the raid took place—at work and in school.

This, shortly after my arrest, was when I learned that I was a drug addict. Withdrawal symptoms set in not long after I was in the jail cell. The next several days were pure hell, for many reasons. I begged for someone to help with the sickness, but my pleas went unanswered.

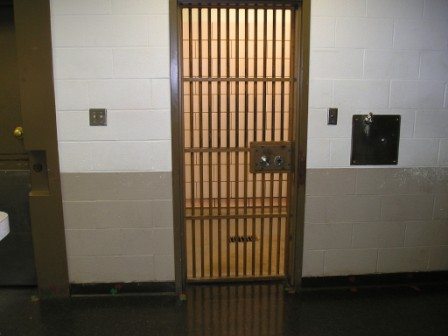

My only contact with humans was through a small slot in the middle of a steel door. As I said, I’d begged for help but that door wasn’t opened again for three days. I did see a couple of hands twice a day when they shoved a food tray through the slot. But the person wasn’t allowed to talk to me.

A federal agent finally came to get me on the third day. He took me to a courthouse for a bond hearing. My family was there but I wasn’t allowed to speak to them. I was denied bond. Why not, I don’t know. This was a first offense, and a $100 dollar offense on top of that. So I was hauled back to the jail cell.

On the ride back to the jail, shackled like Charles Manson—handcuffs, waist and leg chains—I realized just how lovely trees, flowers, and the sky really are, even though I was seeing them through a steel screen. I also realized how important my family was. I’d taken a lot of things for granted in my miserable life.

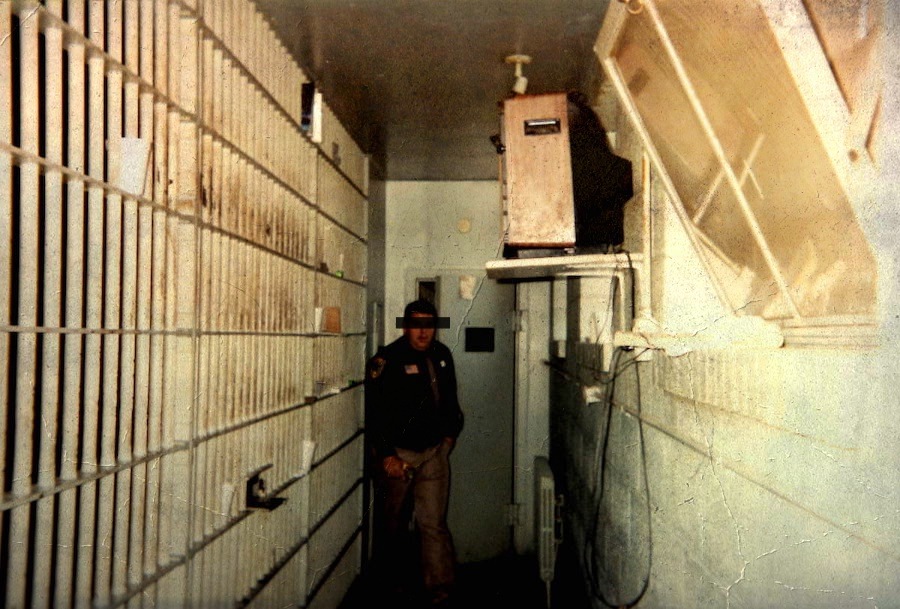

So I wound up back at the jail, which I learned also doubled as a holding facility for federal prisoners. I was there for two more weeks until my wife scraped together enough money—$25,000 (she borrowed against the house)—to retain an attorney to represent me. Still, he obtained a lien on the house in case his fee went above the $25,000. Federal court is really expensive.

The lawyer managed to get another bond hearing and I was released on my own PR, but I wasn’t allowed to go home with my family. I had to stay with a relative in another city because the prosecutor said I was a threat to my community. For $100 worth of drugs that I never took or sold!

Anyway, I remained there until I went to court where I was found guilty (a pre-arranged plea agreement) and sentenced to serve nearly three years in federal prison.

In the beginning, an FBI agent told me Mr. Comey wanted them to question me to see if knew of public corruption. I couldn’t believe it. Somehow he was under the impression I knew something of importance, but I didn’t. Nothing. When I think back, I think he may have a little embarrassed that he’d initiated this huge raid that involved dozens of law enforcement officials, several prosecutors, and lots and lots of money, all for that tiny amount of cocaine (illegal, I know).

So he pushed hard. I also believe that’s why I was denied bond and was held at that way out of the way jail in another part of the state, and that I wasn’t allowed to return home.

The arrest occurred on a Friday, which meant they were guaranteed that I’d remain locked away at least until Monday when the courts were open. Slick move. All to prevent me from telling the story. Prosecutor Comey kept me in seclusion until they could begin the threats of “forever in prison and locking up my family.” It was no longer about the cocaine. This was to save face.

But this is my educated guess and a story for another day.