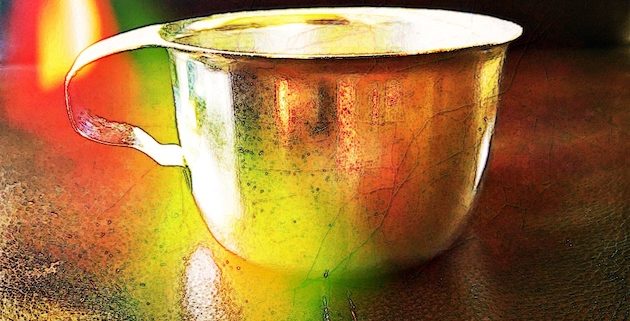

The tin cup pictured above is an actual drinking vessel that was originally part of the fabulous dining experience for prisoners housed inside a small county jail. The lockup itself was every bit as peachy as the cup, and both the building and the stainless steel mug were well past their expiration dates when the county finally gave in and demolished the old place.

As they say, “if those walls could’ve talked” we’d have heard tales of jailhouse coffee potent enough to dissolve steel beams. A cook who somehow transformed liver and onions into a dish that even the pickiest of inmate diners enjoyed. We’d have heard about the two graveyard shift jailers who discovered two whole baked turkeys in the refrigerator and consumed most of the pair of browned birds during the course of their December 24th overnight shift. The turkeys were designated for the prisoners’ Christmas dinner.

The prisoners were still there, locked up when New Years Day rolled around. The jailers were not, courtesy of a very angry sheriff who, at the last minute, had to hire a caterer to prepare additional turkeys for the prisoners.

The old red-brick jail building, if it were able to speak before its demise, might’ve told us about the prisoner who managed to smuggle a gun inside and then dared officers to “come and get it.” Certainly we’d have heard about the roaches and mice and the general funky stench of a place with little ventilation (no air movement at all in some corners of the facility).

The jailhouse could’ve gone into detail about how prisoners were allowed a couple hours of recreation once or twice each month, and that was limited to stepping outside onto a square of concrete for a game of basketball, if the ball was inflated and that was a rarity. The others who didn’t play ball simply sat down or paced back and forth on a small patch of grass next to the court.

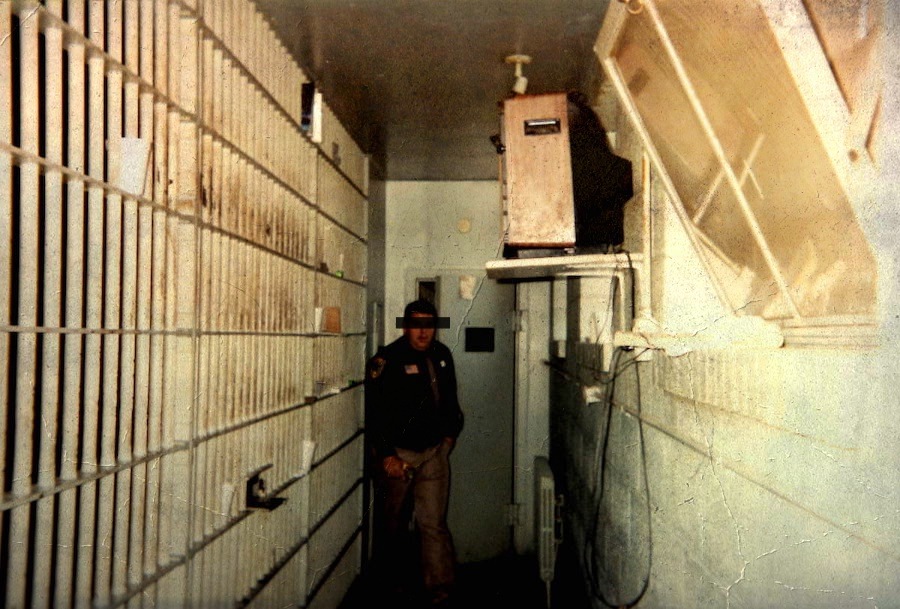

It might’ve spoken of the dangers facing deputies (they were called jailers at this department). Blind corners and stairwells. Hallways so narrow that the jailers were forced to walk next to the bars.

No cameras “in the back” Therefore, when jailers opened the door to enter the lockup area they had no idea what waited for them on the other side. Had inmates escaped their cells, which had happened a couple of times, deputies were sitting ducks for an ambush.

So buckle up and join me for the only peek available inside this small facility. Believe it or not, this place was located in a county within the U.S., not in a third world country. And, it was in use not so long ago.

Follow me, but don’t touch anything, including those top two strands of wire. They’re electrified. A bug zapper for humans!

As we pass through the front gate, after being “buzzed” inside, please look to your right and you’ll see the recreation yard in its entirety, a simple square of concrete with an adjoining and similarly sized patch of grass. Inmates were allowed outside once or twice per month. Since there are no day rooms inside, it was a rare treat to see and do anything that wasn’t inside a dark, damp, and smelly 6×9 concrete cell.

During recreation time two patrol deputies were called in off the road to stand guard outside the fence. They were required to watch over the activities, armed with Remington 870 Wingmaster shotguns. The 870 Wingmaster is often a go-to weapons when in the business of law enforcement.

This, the sheriff’s order to have patrol deputies oversee recreation time, left the county less safe due to having two less deputies available to respond to calls. If an emergency arose the inmates were immediately herded back to their cells. Once they were safely tucked away the two patrol deputies left the jail with sirens yelping, lights flashing, and tires squealing.

Recreation yard

Upon entering this county jail, we first set foot inside a tiny lobby. This was where citizens stood at counter to sign documents, speak with deputies and/or dispatchers, hand over money orders for inmate commissary accounts, file criminal complaints, and report crimes, etc.

The lobby also served as the visiting room. It was where family and friends stood facing one of two small windows that were equipped with sound holes so that inmates and visitors could hear the other speak. No phones and no contact. FYI – should officers arrest and deliver a suspect to the jail they brought them through this lobby area. Therefore, visitors would be made to move behind the business counter, or other nearby area, until the prisoner and officer passed through. Super safe, right?

Visitation and lobby area. This photo was taken from behind the counter where citizens filed reports, etc. The space was quite small.

On visitation day (Sunday afternoon only), inmates were brought two at a time to a small cell where they were locked inside. The cell was on the opposite side of the wall, directly behind the two green chairs in the above image.

Inmate visitation cell.

The two small windows in the visitation cell are the reverse sides of the ones in the previous photo. Until visitations, a piece of cardboard was positioned over the windows to prevent prisoners, the trustees who cleaned the jail and were allowed to roam about freely, from seeing out into the office area/lobby.

Stepping through the doorway leading to the cellblock area (to the right of the green lobby chairs in the photo) we first pass the trustee cells. The door to these cells remained unlocked during daylight hours to allow those prisoners to complete their chores—cleaning, mopping, delivering meals, etc. Trustees were required to be inside their cells by 9 p.m. each evening, where they’d remain locked inside until 5:30 a.m. in preparation for breakfast service.

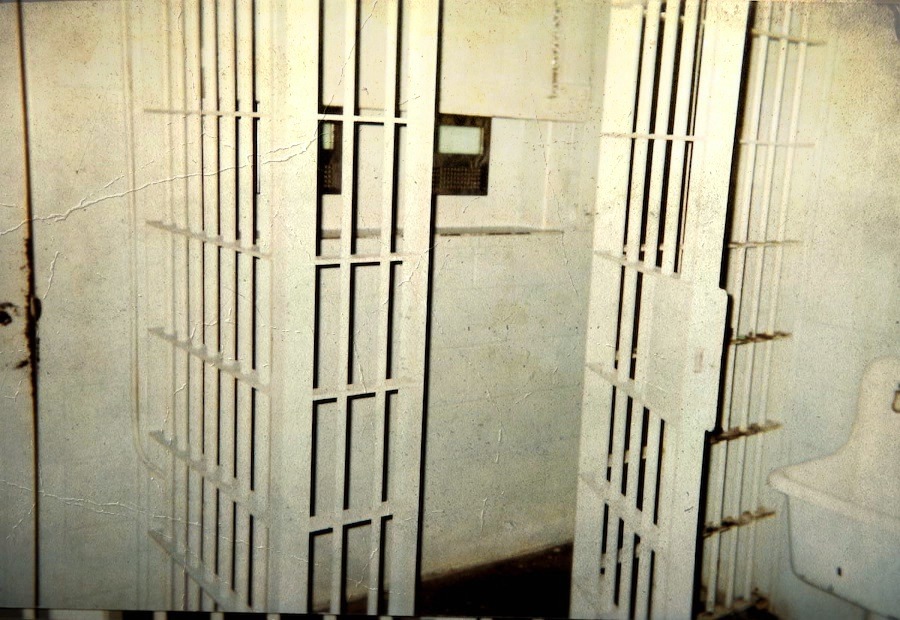

Looking out from inside the trustee cells.

Hallways and corridors were extremely narrow, which was dangerous for the jailers who worked there. The facility was heated by old and clunky boilers that needed constant service and repairs. Radiators were there, inside the corridors, but were scarce. There was no heat inside the cells. And, there was no air conditioning whatsoever.

The only airflow came through small widows. In the next image you can see one of those windows (top left corner), open and tilted in toward the cells. A portable TV sat on a wonky, wall-mounted shelf next to the window.

Narrow corridors are dangerous!

Inmates were not allowed access to the TV controls, and reception was quite poor and was achieved with “rabbits ear” and Loop” antennas. Jailers changed channels when requested, during their rounds. But prisoners will be prisoners, so they manufactured makeshift antenna controls fashioned from string or wires, using the “remote controls” to swivel the antenna to dial in stations. Not allowed but, as I said, prisoners will be prisoners.

Of course, jailers often confiscated the strings and wires, and tightly rolled up newspapers used for reaching across the hallway to change a channel. Those items are considered as contraband in lockup facilities because they can be used to strangle, commit suicide, or attack officers. Newspapers and magazine pages can be rolled and formed in ways that make them nearly as hard as wood and are often found with sharpened objects inserted into the pointed ends. Doing so makes them as lethal as any spear or other stabbing type of weapon. Very deadly.

Wires to rotate rabbit-ear antennas from side to side to help receive a better picture. No cable!

To show just how dangerous this place was for deputies, notice how close the jailer below was to the bars. He had no choice due to the swing direction of the door.

Notice the pieces of white paper poking through the bars. They’re actually envelops placed there by prisoners. This was their version of postal letter boxes. Each morning a jailer collected the envelopes and carried them back to the office where he’d place stamps on each one, if the prisoners had enough money in their account to cover the costs. Afterward, a USPS letter carrier stopped by the jail to pick up outgoing mail and drop off incoming mail.

Jailer enters corridor. Danger!

There were no light fixtures inside the cells. Instead, floodlights mounted to the corridor ceilings illuminated each block of four cells. The fixture below hangs above one of the few windows in the block. Lighting was poor to say the least.

Floodlights gave the impression of peering in at zoo animals on display.

Prisoners received their meals through horizontal slotted openings in the bars. Trustees delivered the trays.

Tray slot

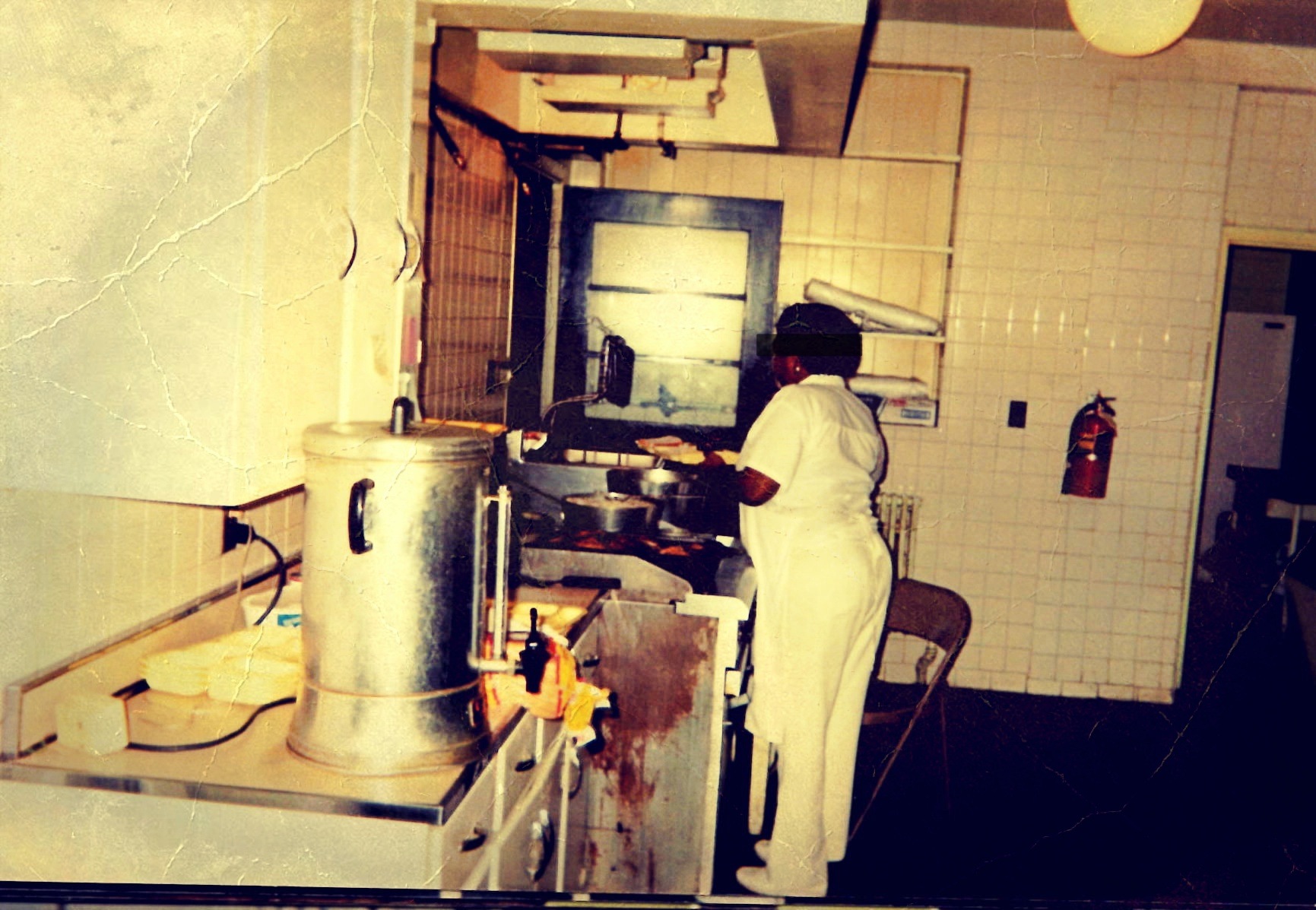

Meals were prepared in the jail kitchen. Trustees received meal trays from the cooks through a pass-through window leading from the kitchen to the jail corridor. Coffee was always available for deputies, 24 hours a day. Inmates were given coffee with their breakfast. One of the perks of being a trustee was to have coffee whenever they wanted, during daylight hours. Deputies and prisoners drank coffee from the same pot, the one pictured on the countertop below.

Jail kitchen

There were no showers inside the cell blocks. Instead, deputies escorted prisoners to showers located in another area … once each week, if they were lucky.

Showers had no floor drains, therefore water spilled out in the same corridors used by the jailers when making rounds.

Showers drained into the corridors.

To open cell doors deputies/jailers used a Folger-Adams key to release a lock on a cabinet attached to the wall outside each block of four cells. The compartment was made of thick steels and contained the door controls. The same key also locked and unlocked all interior jail doors, such as the cell doors, supply closets, access to plumbing and electrical systems, and the main “in/out” door to the jail that connected to the lobby/visiting area.

Folger-Adams key

With the cabinet door unlocked, the jailer opened and closed cell doors using levers and a large wheel. Each lever controlled the lock to one cell door. The jailer pulled the desired lever down to lock a door(s) and then turned the wheel to “roll” the barred doors either open or closed. This was all performed manually. No electronic controls. Should a door not close completely, its corresponding light (below the levers) illuminated with a bright red glow.

The door to the jailer’s right (below) was the entrance to a block of four cells and a very small small, narrow day room. When the jailer opened the cell doors, it released each of those four prisoners into the day room. He’d then roll the doors shut until night. Prisoners were not permitted to remain in their cells during daytime hours.

If a prisoner refused to come out of his cell when required, the others were returned to their cells (for safety) and deputies would then go inside to “gently” coax remove the misbehaving inmate, who would then serve a few days in “the hole” for not following instructions and jail rules. The unruly inmate would also lose commissary and visiting privileges.

Wheel of Misfortune

And that, my friends, was your look inside a place not many have seen. Those who have wish they hadn’t, I’m sure.

Cheers …