Erika Mailman: How To Interrogate a Witch

How to Interrogate a Witch

The Graveyard Shift is an incredible resource for crime writers. Many thanks to Lee for letting me guest blog today. My name’s Erika Mailman and I’m warping the concept of the blog a tad… I’m not displaying the latest crime-fighting gadgets or talking about police procedures. Instead, I’ll discuss the “cops” of the medieval Dominican monastery, the tonsured friars who hunted witches.

Instead of the Macavity-nominated Police Procedure & Investigation, the book that guided friars in their interrogation of witches was the Malleus Maleficarum. Written in the late 1400s by two German inquisitors, this book addresses every question that a witch hunter might ask.

An exceedingly popular book, the Malleus underwent multiple printings. Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press 30 years earlier made possible its widespread dissemination. It’s still in print after 500 years (I got my copy on Amazon), and a more chillingly misogynistic book can’t be found.

In pseudo-reasonable legalistic writing, the friars set about instructing readers how to identify witches, what to do with them once they’re in custody, how to interrogate them, when and how to use torture, and how to determine if the “extreme penalty” (death) is warranted.

In this post, I’ll be highlighting some of the information found in the book.

– Not believing in witchcraft constitutes heresy. The authors knew that in some communities, witch hunters would face opposition from those who argued that witchcraft didn’t exist. Their solution: disbelief in witchcraft became heretical itself. While people might stick their neck out to protect a wrongly-accused neighbor, their willingness would abate if doing so put them under suspicion.

– Women are more likely than men to be witches. The title Malleus Maleficarum, which means “The Witch’s Hammer” (i.e., the book is a weapon to hurt witches with), gives the word “witch” a feminine gender. Although medieval witch woodcuts often depict men and women in equal number, and data shows that in the 1300s both were equally targeted, the Malleus clearly finds women more culpable.

There are two reasons for this. They are “feebler both in mind and body” and therefore unable to resist the Devil’s allure as easily as men. But the second, more overwhelming reason, is that women are unspeakably carnal. The authors in Freudian slippage delighted in describing the various lustful abominations women indulge in. [Remember, friars undertook vows of abstinence.] They wrote, “To conclude. All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.”

– Women steal penises. One of the strangest things women were accused of doing was stealing penises. They either pilfered the member outright, or rendered it smaller. The Malleus devotes incredible amounts of ink to this problem; no less than three full sections deal with the issue. The book earnestly reports that witches “sometimes collect male organs in great numbers, as many as 20 or 30 members together, and put them in a bird’s nest, or shut them up in a box, where they move themselves like living members, and eat oats and corn, as has been seen by many.”

The image of corn-eating phalluses would bring a smile to your face if the consequences weren’t so severe. And so terribly, terribly current. Believe it or not, a penis theft epidemic rages in certain African countries today. As recently as April, Congolese men tried to lynch witches who had stolen their members. In 2001, a mob beset five people in Benin for the crime. Reminiscent of being burned at the stake, the vigilantes doused four of them with gasoline and set them on fire; the arguably lucky fifth was hacked to death.

– They don’t recommend attorneys for these kinds of cases. Although witches desperately wanted someone to speak on their behalf-especially since so many of them lived powerlessly on the fringes of society-they would have to fight to convince someone to do so. Why? Because any advocate of theirs would be defending heresy… and therefore also a heretic. The Malleus states, “Such cases must be conducted in the simplest and most summary manner, without the arguments and contentions of advocates.”

– It’s best that the witch not know who her accusers are. For fear that the witch would demonically retaliate, the Judge suppressed the names of the witnesses. The Malleus does admit that personal feuds may lead to an accusation, and in that case the accused should be released. That sensibleness is tempered, however, by stating that “It is very seldom that anyone bears witness without enmity, because witches are always hated by everybody.”

– The judge and inquisitors must be careful to protect themselves. Lest the witch target them, the officers of the church and court took protective measures. They did not let the witch touch them, and to prevent the evil eye, she would be led into their presence backwards. They wore a necklace called Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God”) that contained consecrated salt embedded in wax. The witch would be shaved (everywhere) to locate any powerful amulets she might’ve hidden on her body.

– How to obtain confession. First, the witch’s friends were brought to her, instructed to tell her that she would be spared her life if she confessed. If that did not work, the Judge would “order the officers to bind her with cords, and apply to her some engine of torture; and then let them obey at once but not joyfully, rather appearing to be disturbed by their duty.” If she still resisted, “let her be often and frequently exposed to torture.”

– What to do after she confessed. Lifetime imprisonment was the proper sentencing for normal heretics. But witches were more than simple heretics; they were Apostates (people who forsake religion). As such, they had to suffer the extreme penalty, even if they were penitent and immediately confessed. Thus, the only value to confession was to avoid torture before execution.

– So… what about that promise to spare her life if she confessed? This forms the most egregious part of the Malleus Maleficarum. The book suggests that the Judge may pass the buck: “The Judge may safely promise the accused her life, but in such a way that he should afterward disclaim the duty of passing sentence on her, deputing another Judge in his place.”

* * * * *

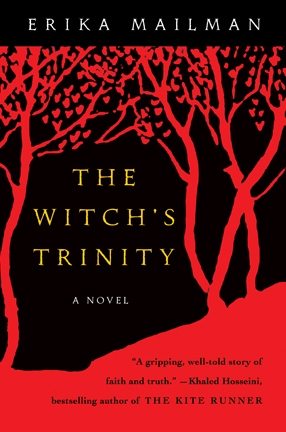

Erika Mailman is the author of the novel The Witch’s Trinity, in which a Dominican friar uses the Malleus Maleficarum to try the main character for the crime of witchcraft.

For more, visit www.erikamailman.com.