Ah, the mind of a mystery writer. Always contemplating the simpler things in life, like car chases, explosions, and murder.

For me, there’s nothing better than to open a book and instantly feel as if I’ve been transported to another world, and I want the character’s emotions and senses to take me there. I want the black, murky waters of James Lee Burke’s Louisiana swamps to fill my gut with a sense of foreboding. I want to feel and smell the humid southern air after a crab boil, and I want to experience the heartbreak that Dave feels when his wife dies. Those things are important to me as a reader, and they’re even more important to me as a writer. I want readers to see, feel, taste, and hear what I write.

Setting can be an antagonist, such as stories featuring humans (the hero) battling and overcoming the forces of nature (the antagonist)—hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, blizzards, etc.

As a reader, I also pay a lot of attention to the names assigned to fictional characters and locations because they also tell us a little bit about the author. Like the town names Hope and Despair that Lee Child used in his book Nothing To Lose.

The road leading to Hope was fresh, new, and smooth ( as smooth as the author). The road to Despair was in disrepair, filled with potholes and was totally worn out. Using those two simple words (Hope and Despair) was brilliant. Lee typed eleven letters and told us a story about two towns that some couldn’t have achieved in a dozen pages.

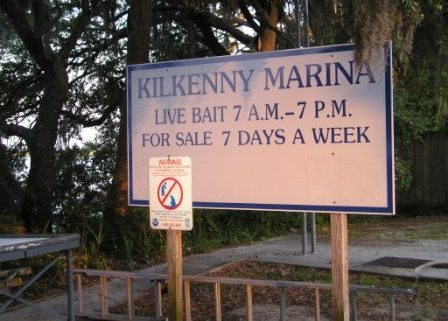

Now, speaking of appropriate settings and naming of towns in crime novels, how about the name in the photo above—Kilkenny Marina? How’s that for a great place to set a story? I suppose we’d need a few facts, first. Like, who’s Kenny? And why do the folks at the marina want to kill him? What exactly does one fish for at Killkenny? And what, exactly, would our characters use as bait? Pieces of Kenny would, of course, be a perfect means of destroying the evidence of murder, right?

Setting allows readers to step into the pages of a story and then to exist there alongside the characters as they move through the tale.

A name alone can serve as a great hook. After all, catchy names can also become a familiar link between fans and their favorite stories/books—Metropolis (Superman), Bedrock (The Flintstones), Whoville (The Grinch and Horton Hears a Who), and Emerald City (The Wizard of Oz), to name a few.

Anyway, Denene and I once stumbled across this little jewel of a place—Kilkenny Marina—while exploring the back roads near Savannah, Ga.

Instead of hanging a right onto Belle Island Road in Richmond Hill (south of Savannah) I kept straight and this is the little slice of heaven we found after passing through the narrow opening in a stand of massive live oaks. A perfect setting for a mystery? Perhaps we should find Kenny to ask his opinion of the situation, if he’s still alive.

Great settings activate the reader’s senses by using smells, colors, textures, sounds, and sensations.

Sounds are part of setting, such as waves gently licking and lapping against the hull of a boat. Odors are also bits of setting, like how the scent of salty air mixed with fumes of gasoline and sun-drying oyster shells, bait fish remnants, and seaweed take us to the decks of fishing boats.

By the way, who says you have to die to see the light at the end of the tunnel? As a more practical means of having a peek at “the light,” simply visit Kilkenny Marina a few minutes before sunset and this is what you’ll see on your way out.

Regarding setting, though, our decisions are often based upon what we see. In the case of blinding sunlight, a character may squint, pull down a car’s sun visor, hold up a hand to shield their eyes from the bright light. A person who’s blind may react to the sudden warmth on their face.

So yes, setting can be a character, one who evokes emotion and adds layers and depth to a story. It’s also a place for the story to take place. It’s atmosphere and mood, and the antagonist who creates tension.

More examples of using setting to activate a reader’s senses:

Patricia Cornwell didn’t invent rain, leaves, or playing fields, but she obviously drew on her memories to create the passage below. It’s a simple scene, but it’s a scene I can easily picture in my mind as I read. I hear the rain and I feel the cool dampness of the asphalt, grass, and tile roof. The writing also conjures up images of raindrops slaloming down windowpanes, and rushing water sweeping the streets clean of debris. The splashing and buzzing sound of car tires pushing across water-covered roadways.

“It was raining in Richmond on Friday, June 6. The relentless downpour, which began at dawn, beat the lilies to naked stalks, and blacktop and sidewalks were littered with leaves. There were small rivers in the streets, and newborn ponds on playing fields and lawns. I went to sleep to the sound of water drumming on the slate roof…” ~ Patricia Cornwell, Post Mortem.

Sandra Brown takes us on brief journey through a pasture on a hot day. We know it’s hot because of the insect activity. We also know the heat of the day increases the intensity of the odor of horse manure. And, Brown effectively makes us all want to help Jack watch where he steps.

“Jack crossed the yard and went through a gate, then walked past a large barn and a corral where several horses were eating hay from a trough and whisking flies with their tails. Beyond the corral he opened the gate into a pasture, where he kept on the lookout for cow chips as he moved through the grass.” ~ Sandra Brown, Unspeakable.

Close your eyes for a moment and picture yourself walking into a bar, or restaurant. What do you see? Can you transform those images into a few simple words? How do you choose which words to use? Which words will effectively paint the picture and take the reader with you on your visit to the bar?

Here’s a decent rule of thumb – Write the scene and then remove all of those unnecessary flowery words, especially those that end in “ly.”

Too many “ly” words are often difficult for readers to take in. Besides, they can slow the story and do nothing to further it.

Lee Child is a master when it comes to describing a scene with few words. Here’s a fun exercise. Count the number of times Child uses an “ly” word in the text below. Then consider whether or not you would have used unnecessary “ly” words had you written this scene? Think maybe it’s time to step away from them?

“The bar was a token affair built across the corner of the room. It made a neat sharp triangle about seven or eight feet on a side. It was not really a bar in the sense that anybody was going to sit there and drink anything. It was just a focal point. It was somewhere to keep the liquor bottles. They were crowded three-deep on glass shelves in front of sandblasted mirrors. The register and credit card machine were on the bottom shelf.” ~ Lee Child, Running Blind.

Another example of effectively and masterfully projecting an image into a reader’s mind comes from James Lee Burke. Short. Sweet. And tremendously effective.

“Ida wore a pink skirt and a white blouse with lace on the collar; her arms and the top of her chest were powdered with strawberry freckles.” ~ James Lee Burke, Crusader’s Cross.

*UPDATE – We never found Kenny, so we assumed the deed had been done prior to our arrival. His disappearance remains a mystery …