Police officers must attend training academies where they learn the basics of the job. In Virginia, for example, it is required that new officers receive a minimum of 480 hours of basic academy training that includes (to name only a few subjects):

- Professionalism

- Legal

- Communication

- Patrol

- Investigations

- Defensive tactics and use of force

- Weapons, including firearms, baton, chemical, etc.

- Driver training

The list sounds simple but, believe me, the training is grueling and physically and mentally challenging and demanding. It’s also quite stressful because if a rookie happens to flunk any portion of the academy they are immediately returned to their department where it’s likely their employment will be terminated.

Of course, academies and individual departments may add to the basic curriculum, and they often do (mine was longer), but they may not eliminate any portion of the training that’s mandated by the Department of Justice and/or the state.

In addition to the basic police academy, in order to “run radar,” officers are required to successfully complete a compulsory minimum training standards and requirements course. This course is specifically for law-enforcement officers who utilize radar or an electrical or microcomputer device to measure the speed of motor vehicles.

The Basic Speed Measurement Operator Training requirements include the following:

- Attend a DCJS approved speed measurement operator’s course

- Pass the speed measurement testing

- Complete Field Training

Virginia State Police Basic Training

Academy training for the Virginia State Police (VSP) is much more intense and lengthy than that of local academies.

VSP academy training includes 1,536 hours of instruction covering more than 100 sessions that range from laws of arrest, search and seizure, defensive tactics, motor vehicle code, criminal law, and much more.

A troopers basic training is completed in four phases.

- Phase I – The first 12 days are at the Academy at which time the students receive abbreviated training.

- Phase II – Pre-Academy Field Training—up to four months—at which time the students ride with a FTO.

- Phase III – Return to the academy for 26 weeks of Basic Training, completing both classroom and practical courses.

- Phase IV – Following graduation from the academy, troopers complete an additional six to eight weeks of field training with a FTO.

What Happens After Local Officers Graduate From the Academy?

Once local police and sheriff’s deputies complete the minimum of twelve weeks of academy training (remember, some are longer), the law enforcement officers are then required to successfully complete a minimum of 100 hours of approved field training. This is on the job training, working in the field under the supervision of a certified field training officer (FTO). FTOs, by the way, must attend and successfully complete a training program that qualifies them to train officers in the field.

The mandatory minimum course for FTOs shall include a minimum of 32 hours of training and must include each of the following subject matter:

a. Field training program and the field training officer.

b. Field training program delivery and evaluation.

c. Training liability.

d. Characteristics of the adult learner.

e. Methods of instruction.

f. Fundamentals of communication.

g. Written test.

During the field training portion of a rookie’s beginning days on the street, their FTOs are evaluating their performance while at the same time protecting them and the public from harm. Working as an FTO is a tough job. I know, I’ve done it. You’re forever watching to make certain the rookies do not accidentally violate the rights of citizens, and you’re constantly on high alert, watching for the unexpected. This is because you’re responsible for everything that could happen. And, you’re watching for two people instead of one.

FTOs typically allow rookies to get their hands dirty by handling calls, getting the feel of driving the patrol car on city streets or county roads, conduct arrests, etc. They serve as a crutch, to prevent missteps. They’re leaders and they’re teachers. They are the final barrier to the officers going out on their own, a day most new officers salivate for in anticipation.

That first night alone in your very own patrol car is a highly desired moment. It the official sign that you’ve made it. You are finally a police officer. In the meantime, though, there are a lot of boxes that must be checked off by the FTO.

During the field training period, each rookie must demonstrate that they know the streets in their patrol areas. They must know local and state laws and ordinances. They must know the working of the court system and how to effectively interact with local prosecutors. And, well, below is a list of topics that rookies must know better than the backs of their hands before their FTO officially signs the paperwork releasing them from the training.

- Department Policies, Procedures, and Operations (General Law Enforcement)

- Local Government Structure and Local Ordinances

- Court Systems, Personnel, Functions and Locations

- Resources and Referrals

- Records and Documentation

- Administrative Handling of Mental Cases

- Local Juvenile Procedures

- Detention Facilities and Booking Procedures

- Facilities and Territory Familiarization

- Miscellaneous

Academy instructors aren’t simply any Joe or Sally off the street who may know a little something about police work because they’ve every episode of COPS, twice. Instead, academy instructors in Virginia are well-trained and must meet a minimum standard set by the state/DOJ.

Yes, academy instructors are required to attend specialized certification classes for the specific subjects they teach. And, instructors who train/teach and certify other instructors must become certified to teach those high level classes. They are then certified instructor-trainers.

I was a certified instructor-trainer for Defensive Tactics and CPR, and I was a certified instructor for Firearms, Officer Survival, CPR, and Basic and Advanced Life Support.

Advanced Classes for Officers, and Writers

Officer training never ends. Laws change and tactics and techniques evolve. Academies and agencies across the U.S. offer numerous specialized training opportunities. A great example of such educational opportunities are the courses offered at Sirchie, the location of the 2019 Writers’ Police Academy’s special event, MurderCon.

Each year, on a continuing basis, Sirchie offers advanced classes for law enforcement officers. If some of these sound familiar to you, well, they should, because they were made available to attendees of the 2019 Writers’ Police Academy. It was an extremely rare opportunity for writers to have the opportunity to go behind the scenes and train at such a prestigious facility and to learn from some of the top instructors in the world.

Classes presented at Sirchie, for law enforcement officers, are as follows:

-

Clandestine Grave Search & Recovery

SIRCHIE is offering a 4 day “hands-on” training class on searching for and properly investigating and recovering remains from a clandestine grave site. The legal term corpus delicti me… -

Phase 1 – Footwear Impression – Detection, Recovery, Identification Training

Footwear impression evidence is the most overlooked evidence at crime scenes. Criminals will often wear gloves or wipe down objects that they touch at crime scenes but rarely do they remove their s… -

Bloodstain Pattern Documentation Class

Throughout the United States and certainly in smaller departments, the crime scene technician faces the complexities of homicide scenes without the proper support or training. Like all forensi… -

Mastering the IAI Latent Print Exam Class

Minimum requirements for the class: Each student must have at least 1 year of Latent print experience to be accepted in the class. Background: Examiners who are preparing to take the L… -

Digital Device Forensics

With over 9 Billion wireless subscriptions worldwide as of 2016, every criminal investigation involves information that can be captured from a digital device, including phones and tablets. Understa… -

Latent Palm Print Comparison Class

Minimum Requirements for the class: Each student must have attended and completed a Basic Latent Fingerprint Comparison Course to be accepted in the Advanced Latent Palm Print Comparison Cou… -

Evidence Collection and Processing Training

Our Evidence Collection and Processing Training Program provides law enforcement professionals and crime scene investigators with hands on training using forensic tools that will help to execute th… -

Drone Forensics

This 5 day course is designed to take the investigator deep into the world of Drone Forensics. The use of Drones is growing rapidly and expanding to criminal enterprises and terrorist organizations… -

Comprehensive Advanced Latent Print Comparison Course

How proficient are your individual comparison skills as pertaining to latent print casework? Are erroneous exclusions a problem in your skill set? If you are a manager are erroneous exclusions a problem in your latent print work unit? This class was developed to help improve latent comparison competency and knowledge whether you are already a Certified Latent Print Examiner or if you are preparing to take the exam in the near future. A broad and exhaustive level of complex latent print exercises were carefully compiled to improve the level of expertise for examiners. You will not find another class like this one anywhere.

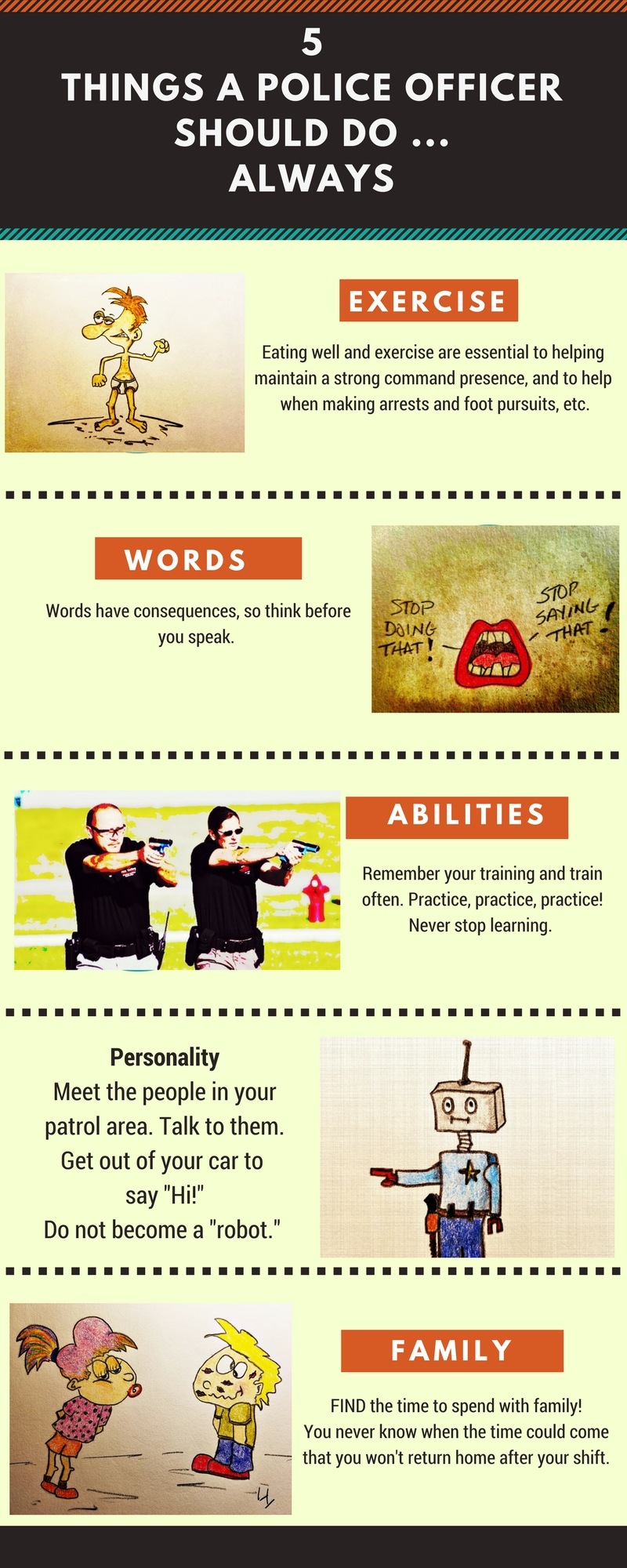

So Much Training and So Many Required Certifications, but …

Law enforcement officers in Virginia (I’m not certain about other states) shall satisfactorily complete the Compulsory Minimum Training Standards and Requirements within 12 months of the date of hire or appointment as a law-enforcement officer.

Take a moment to re-read the line above and then let it sink in that officers may work for up to one full year before they attend a basic police academy. That’s potentially 12 months of driving a patrol car and making arrests without a single second of formal training.

Sure, most departments would never dream of allowing an untrained officer work the streets without close and direct supervision. However, I’ve seen it done and I have personal knowledge of deputy sheriffs who patrolled an entire county, alone, for nearly 365 days prior to attending any formal police training. I know this to be so because I was one of those deputy sheriffs.

Believe me, it’s an odd feeling to carry a loaded gun while driving like a bat out of hell with lights and siren squalling at full yelp during the pursuit of a heavily armed suspect, all while not having clue what you should and shouldn’t do when or if you catch the guy.

When I think about it today I realize how foolish it was for my boss to allow us to work under those conditions.

Author Melinda Lee – WPA firearms training

Thanks to the Writers’ Police Academy, many writers have received far more training than I had during my first year on the job. Actually, many writers who’ve attended the WPA have received more advanced training than many of today’s law enforcement officers.

Here’s a recap of past Writers’ Police Academy events condensed in an ad for the 2018 WPA.

Spots are still available to the 2018 Writers’ Police Academy. Yes, registration is still open and, we have lots more surprises on the way. This is an event you’ll remember for a lifetime so please hurry while slots are available! Oh, be sure to refer a friend and have them sign up as well. You’ll soon see why that could be a very important step.

Spots are still available to the 2018 Writers’ Police Academy. Yes, registration is still open and, we have lots more surprises on the way. This is an event you’ll remember for a lifetime so please hurry while slots are available! Oh, be sure to refer a friend and have them sign up as well. You’ll soon see why that could be a very important step.