New York Times Bestselling Author Allison Brennan is a former consultant in the California State Legislature and lives in Northern California with her husband and five children. Her eighth romantic thriller, TEMPTING EVIL, is on sale 5/20/08.

Truthful Fiction

I make-up stories. My books are fiction and I’m an expert at nothing. I know a little bit about a lot of stuff, which is both a blessing and a curse.

I’m keenly aware that I don’t know everything (please, do not tell my children this fact!) I did a bit of research for my first three books-just enough, frankly, to realize that I had become dangerous-to myself.

There are two mistakes beginning writers-many of whom are published-make. The first is to not do any research and make up everything, stretching credibility. I’m willing to suspend disbelief if the story and writing is good enough, but some things I have a hard time forgiving. The other extreme is putting in too much information. You learn something new, become an “expert” on-for example-how internet feeds can hide their location. Then you show-off your knowledge to your readers, often resulting in long, boring passages. And unless you ARE a computer expert, you’re going to get something wrong.

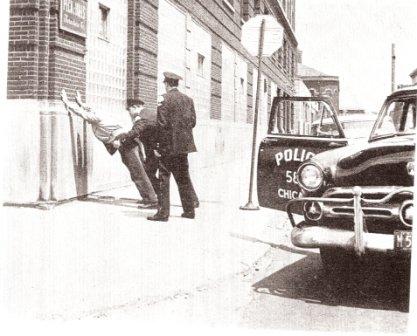

I received some great advice from two published author friends of mine. The first is married to a retired cop. She laughs at errors in books related to law enforcement. She told me, “Less is more.” Don’t over-explain because unless you’ve walked the beat, you really don’t know much about being a cop. My other friend, a retired FBI Agent, said, “You’re writing fiction. You can make it work.”

Yes, I write fiction and therefore I can break and bend a lot of rules. But because I really want my stories to have a flavor of reality, I want them to be as accurate as possible. I’ve become addicted to research.

Right now, I’m in the middle of the FBI’s Citizen’s Academy. This is the most fun I’ve ever had learning something new. The reason I wanted to do this was because I’m launching an FBI series in early 2009, but in my current “Prison Break” trilogy I have FBI agents as either major or secondary characters.

The premise of my series is the “best of the best” Evidence Response Team members form a unit at Quantico to handle high-profile and complex cases, like multi-jurisdictional serial killers, mass murderers, and kidnappings. I’ve done a lot of research on ERT and am fascinated by their dedication and training. ERT members train and specialize in different areas, like firearms, bombs, forensic anthropology, etc. They are full Special Agents, but have an added skill or talent and are sent out to crime scenes to collect and process evidence like a traditional local criminalist would do. One high-profile case they worked near where I live was the Yosemite murders. The ERT unit processed the burned car where two of the victims were found. They are used on federal cases or when local law enforcement requests help-particularly helpful in smaller districts who can’t afford their own crime scene team.

I was very happy with my premise, until I talked to the PR guy at my local FBI office and learned that the beauty of the ERT program was that each of the 56 regional offices has an ERT and the purpose is to be able to respond quickly to a crime scene. Having a national unit sort of defeats the purpose of the program.

I was a bit upset learning this. But, because this is fiction, I figured I would just go with my original plan. I’ll admit, I’d lost a little love I had for the series and was considering coming up with a completely different idea.

My first night at the citizen’s academy, we learned the priorities for the FBI. After 9/11, the number one priority is counterterrorism. No brainer there. Protecting our country from another terrorist attack, foreign or domestic, is crucial to the health and safety of the public.

The second priority is counterintelligence. Then Cyber crimes (which includes online child pornography.) Then public corruption. Followed by civil rights, criminal enterprises (RICO), white collar crime, and finally . . . violent crime.

Violent crime was at the bottom of the list. This doesn’t mean that the FBI won’t get involved in a case when asked by local law enforcement-they will. But it means that the violent crime squad has fewer staff and resources than the other units. This is largely because violent crime generally stays within local law enforcement jurisdiction, and local cops are well trained to handle robberies and homicides and other such crimes. If a life is in immediate danger-such as the kidnapping of a child-the FBI will make that the number one priority. But for all intents and purposes, violent crime is no longer a priority.

This actually works very well for my FBI series premise. Why? Because if violent crime is not a priority of the bureau, then having an elite team focused on violent crimes has merit. To be honest, I highly doubt that the FBI in this current global climate would create a national ERT unit to focus on violent crime. BUT I can make it work for my story-which is fiction.

In my book FEAR NO EVIL, a very small sub-plot revolved around the disappearance of Monique Paxton. We (the readers) know that she was murdered by the villain. What we learn near the end of the book is that her family never knew her fate. When one of the villains reveals the information about her murder and how her body was disposed, her father finally has closure. In one paragraph I created the backstory for my entire new premise without intending to do so. Jonathon Paxton, Monique’s father, ran for public office on an anti-crime platform after Monique disappeared. Over the years, he worked himself up into higher and higher offices, and is now a US Senator, all on a strong anti-crime platform.

We’re now getting into an area I know something about. After 13 years working in the California State Legislature, I know that lots of legislators come in with pet projects. If it’s something we don’t like or it only benefits their individual district, we call it pork. If it’s something we do like, we call it desperately needed legislation. So in my first FBI book, SUDDEN DEATH (4/09) I’m using Senator Paxton as the vehicle to get funding for a special FBI squad that focuses on violent crime-serial killers, mass murderers, missing and exploited children, and kidnappings.

My premise holds. Likely? Probably not. Plausible? Absolutely. I can sell the idea because Senator Paxton believes strongly in this, so strongly he’s willing to put his political future on the line to fund the program through a budget trailer bill. If his character is strong enough, I think all my readers will believe in not only the program, but that it could be done in real life.

There are a lot of misconceptions about the FBI and what they do (and don’t do.) Before 9/11, the FBI was a reactionary agency. A crime occurred, they investigated. Now, the FBI is proactive, hence the focus on counterterrorism and counterintelligence. They want to stop disasters before they happen.

Most of the successes of the FBI and the other national agencies are classified. We’re not going to read about them in the newspaper. Sleeper cells destroyed, terrorists taken out over seas, stopping an attack by having a strong presence at a major event. People become complacent when there’s nothing big or sexy being reported. They think, wrongfully, that terrorism isn’t a threat any more, or the terrorists who attacked on 9/11 were a few crazy idiots. But the threat is there, and it’s not going away, and our diligence and strength is keeping them at bay.

There’s so much more I could write about! I’ve had three classes (and a day at the gun range) and each day I came up with an idea for a book. One of them I’m really excited about because it centered around an informant whose motivations and conflicts were so clear in my mind that I could see her as a fully-developed character.

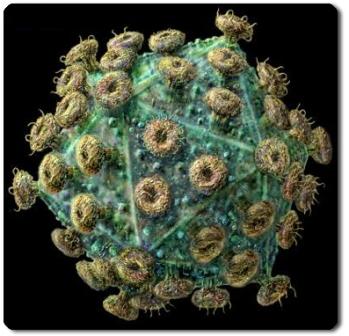

I’m going to wrap this up and visit again in a couple of weeks with more details about how the FBI operates and how to use it-or not-in fiction. But I thought I’d go on my bully pulpit for a moment and discuss the other night’s final presentation on cybercrimes against children.

The SSA in charge of this unit takes his job seriously. Child pornography is a widespread and devastating crime. We’re not talking about naked kids in a bathtub; we’re talking about violent and abusive sexual assault against children-the majority of them infants and toddlers. Yes, babies and small boys and girls. There’s a threshold that the FBI looks into-the child has to be 12 or under. Prepubescent. This isn’t to say that the FBI won’t get involved in a violent crime against a teenager, but because the breadth of this problem, they have to prioritize their resources to protecting and rescuing the youngest of the victims.

Those who prey on the most innocent of the innocent should be dealt with harshly, but unfortunately, as the SSA said: “There is not enough law enforcement in the country to combat this problem.”

If every cop in America focused on child pornography, they’d make only a dent in the distribution of these hideous videos. A recent law enforcement operation discovered 20,000 computers in Virginia alone with downloaded child pornography videos. Yes-videos of sex with young children that are downloaded off the Internet every minute of every day. Over 20,000 sick perverts who watched sexual violence against children.

One case study showed that it doesn’t take long for a adult porn addict to turn to child pornography. A 60-year-old-man was arrested for enticing a 15-year-old girl to commit sexual acts over a webcam. He’d been a legal adult porn addict his entire life, and in one chat room had an exposure to child porn. At first he rejected it, disgusted. But over a few months, he’d become desensitized to the adult porn that had satisfied his addiction for decades. He started looking at more violent porn, then child porn, then violent child porn, then he reached out to victims. This downfall took eight months. Eight months from exposure to child porn to attempted sexual assault.

These men and women who spend countless hours chatting with these men online in order to stop them, viewing child porn videos in the hopes of identifying the child in order to rescue him/her, need to be commended for their dedication and commitment. It is not easy to view the hideous and disturbing videos that are available online. Each child in these videos is a victim of violent, sexual abuse. Most of the law enforcement officers and support staff use their own time to track these predators, in addition to their regular jobs. Truly unsung heroes.

I’m happy to answer questions if anyone has them. I’ll post in a couple of weeks more information about the academy and how to use crime research in novels.

Lee, thanks so much for having me today!

You can visit Allison on her website http://www.allisonbrennan.com/

Allison also writes a weekly blog over at Murder She Writes

http://www.murdershewrites.com/

***

Tomorrow – Scott Hoffman, Owner/Agent of Folio Literary Management