Relationships between Cops and Reporters

In this hectic digital age where editors don’t have time to wait for confirmation lest another outlet beats them to the finish line of a glowing tablet screen, reporters can no longer buy the neighborhood flatfoot a cup of coffee to get the inside scoop on whether Mrs. McGillicuddy offed her old man or whether the lush really did ‘accidentally’ fall out of his bedroom window.

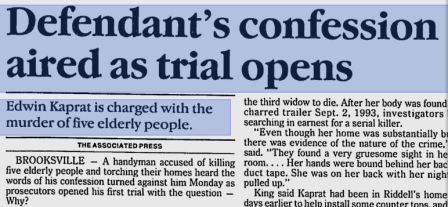

Now, a reporter has to hustle to keep up with the bloggers and the 24 hour cable shows, do anything he or she can to win the few moments of a customer’s attention from an overwhelming amount of other options … and nothing gets attention more than fear. Your kid’s school bus may have bad brakes, your diet soda may be poisoning you, terrorist cells are operating in nice neighborhoods just like yours, and somebody shot somebody else two blocks from where you work. So while the cops are trying to assure the locals they’re responsible for that things are fine, nothing to see so let’s move it along, the news media is trying to convince every single hard-working, tax-paying, mouse-clicking viewer that the exact opposite is true.

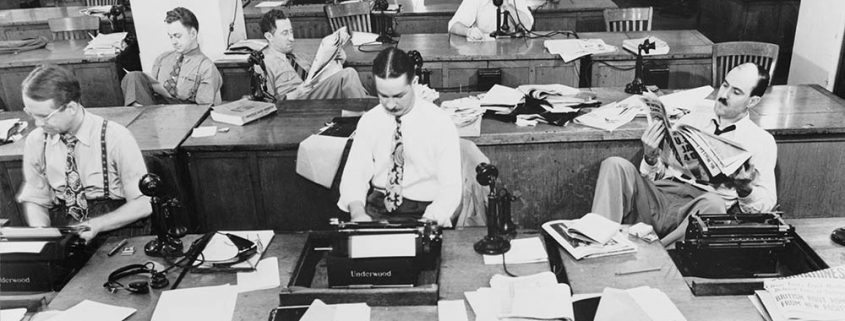

But it didn’t used to be that way. Back in the first half of the last century, reporters and cops had much more interactive working habits. From roughly the 1930’s to the 1950’s were the golden years of newspapers and bosses like Hearst and Pulitzer had deeper pockets than the local constabulary. Reporters were not tasked with rules of evidence and could mislead, con and flat-out impersonate in order to get witnesses to talk. They could then trade this information with the cops to get other information; thus the cops received tips they might not have otherwise. Reporters wanted a scoop and cops, especially the higher-ups, liked to strike an Elliott Ness pose in the papers.

But it didn’t used to be that way. Back in the first half of the last century, reporters and cops had much more interactive working habits. From roughly the 1930’s to the 1950’s were the golden years of newspapers and bosses like Hearst and Pulitzer had deeper pockets than the local constabulary. Reporters were not tasked with rules of evidence and could mislead, con and flat-out impersonate in order to get witnesses to talk. They could then trade this information with the cops to get other information; thus the cops received tips they might not have otherwise. Reporters wanted a scoop and cops, especially the higher-ups, liked to strike an Elliott Ness pose in the papers.

Reporters had many advantages over the cops—they didn’t punch a time clock and could work irregular hours for a boss who wasn’t above paying a witness for their story. Afterwards they’d be happy to turn the information over to the cops, and even hold back part of it if the investigation required it—provided they eventually got to scoop their rivals. A city became a trading floor of information, with each side working the other to their advantage. There would be toes trod on and feelings of annoyance, but the next day the bell would ring and it would all begin again.

Investigative Reporting is on the Decline

When did this change? Hard to say. Rules in all lines of work have tightened, so perhaps cops are no longer so comfortable with spilling a tip over a cup of joe. Certainly the deep pockets have disappeared. Revenues from newspapers and other media plummeted over the same decades in which owners and shareholders came to expect higher profits. And as one of my reporter characters tells us, “You know what is first to get the ax? Investigative reporting.

It’s the least cost-effective type of content in any newspaper—any news outlet, period. Editors and producers can pump months of salary, overtime and expenses into a topic and then it doesn’t pan out. They never get a usable story—wasted money, in their eyes. Corporations hate to waste money that could be going into shareholder dividends instead.” The period of mutual cooperation has given way to a leaner, meaner, more desperate milieu.

It’s the least cost-effective type of content in any newspaper—any news outlet, period. Editors and producers can pump months of salary, overtime and expenses into a topic and then it doesn’t pan out. They never get a usable story—wasted money, in their eyes. Corporations hate to waste money that could be going into shareholder dividends instead.” The period of mutual cooperation has given way to a leaner, meaner, more desperate milieu.

And in that cauldron of pressure forensic scientist Maggie and homicide detective Jack have to solve a series of murders for which, this time, Jack is not responsible.

So far.

Lisa Black

Lisa Black has spent over 20 years in forensic science, first at the coroner’s office in Cleveland Ohio and now as a certified latent print examiner and CSI at a Florida police dept. Her books have been translated into 6 languages, one reached the NYT Bestseller’s List and one has been optioned for film and a possible TV series.

background: #bd081c no-repeat scroll 3px 50% / 14px 14px; position: absolute; opacity: 1; z-index: 8675309; display: none; cursor: pointer; top: 36px; left: 20px;”>Save