David Corbett is the author of three critically acclaimed novels: The Devil’s Redhead, Done for a Dime (a New York Times Notable Book), and Blood of Paradise-which was nominated for numerous awards, and was named both one of the Top Ten Mysteries and Thrillers of 2007 by the Washington Post and a San Francisco Chronicle Notable Book. His fourth novel, Do They Know I’m Running?, will be published in early 2010. His short fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies, including San Francisco Noir and Phoenix Noir, and his story “Pretty Little Parasite” (from Las Vegas Noir) was selected by guest editor Jeffrey Deaver for inclusion in Best American Mystery Stories 2009. David has also contributed a chapter to the world’s first serial audio thriller, The Chopin Manuscript, which won an Audie Award for Best Audio Book of 2008, and its follow-up, The Copper Bracelet. For more, go to www.davidcorbett.com.

A Writer, a PI, and a Duck Walk into a Bar . . .

By David Corbett

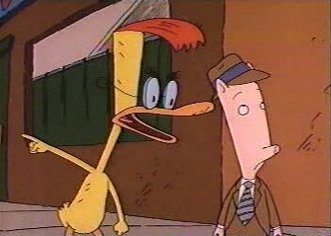

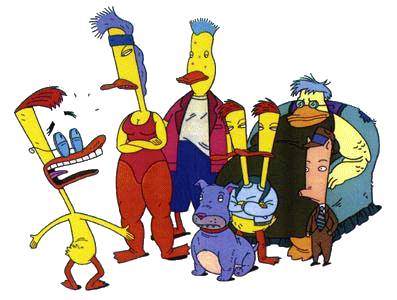

It says a lot about me, I suppose, that my favorite fictional portrayal of a private investigator is a cartoon character named Duckman.

Then again, it is also true that my older brother-a “human factors engineer” (read: research psychologist with a security clearance) who spent his career working for the Defense Department (current specialty, unmanned drones-which apparently feel traumatically inferior to manned aircraft)- once remarked that it was “frightening” to see how much of my personality was formed by Rocky and Bullwinkle.

Duckman, which ran on the infamous USA channel, known primarily at the time for near-continuous Wings reruns, featured a sexually degenerate, compulsively spiteful, savagely violent, hopelessly incompetent and wildly self-deluded duck who seemed to suffer from an anatine variety of borderline personality disorder.

Weirder still, his pupils and eyebrows vanished when he removed his glasses.

He benefitted from possessing the voice of Jason Alexander (on hiatus from his role as George Costanza on Seinfeld), and was aided by a stellar cast of freaks who were all vastly more functional than he was: in particular, a sidekick known as Cornfed, a dapper, insightful and lowkey piglet with the voice of Joe Friday and an encyclopedic knowledge of damn near everything (guess who did the crime solving).

Other characters included a buff, leotard-clad sister-in-law named Bernice whom I found strangely alluring, despite the bill and webbed feet (I have eccentric tastes); three sons-Ajax the dullard (with the voice of Dweezil Zappa) and the genius Siamese twins, Charles and Mambo; and finally two squeaky-voiced, pathologically upbeat and PC stuffed bear assistants named Fluffy and Uranus, who routinely got tortured, shredded, burned alive or otherwise hideously abused by Duckman in one of his customary fits of pique.

God, I loved that show.

(Oh, did I mention that in one episode, there appeared a would-be presidential assassin named, I kid you not, Lee Harley Kozak?)

When it came time to write my first novel, I considered a PI protagonist, but couldn’t quite get with the program. The PI novels I read were really just urban westerns, featuring some variety of the lone gunman, a character that bore no resemblance to me or what I did in my real-world job as a private investigator. We didn’t square off against the bad guys in a hail of gunfire. Normally, the bad guys were our clients. If we squared off, it was over how much money they owed.

I considered the more quasi-legalistic type of PI novel, a first cousin to the legal thriller, but even in the best of these, the defendant is almost always innocent. This again bore little resemblance to my job. I always fought vigorously for my clients, and did everything in my power to find evidence that would undermine the prosecution’s theory of the crime or impeach the informant (we sometimes blithely referred to ourselves as the Snitchbusters-Who ya gonna call?). But I had few illusions concerning my clients’ innocence. (To their credit, neither did they.) In many cases, their indictments were salted with a few gratuitous crimes they didn’t actually commit-oh, those fun-loving snitches-and I felt proud to whittle the number of charged crimes down to a more truthful number before sentencing, but this isn’t what the American crime-reading public wanted. They want their defendants absolved. I had no clue how to deliver.

The other grand illusion of PI novels is the allure of the private client, the ordinary citizen (read: babe) who walks through your office door with a terrible problem-often involving some form of blackmail or extortion, usually resulting from some itsy-bitsy indiscretion, with or without barn animals-and this poor victim of fate needs the tireless advocacy of the intrepid PI, the man who, in the immortal words of Raymond Chandler, can walk the mean streets but who is not himself a mean streetwalker (something like that).

Truth is, PIs loathe private clients. These creatures routinely feel certain they know exactly what happened, and you’re being hired simply to confirm their self-serving delusions. When you come up with something different-the truth, for example-they refuse to pay.

Guilty men with lots of money are the gravy train of real PIs. Unfortunately, they don’t make good fodder for the kind of crime novels Americans like to read.

You may have caught a somewhat jaundiced opinion of the American reading public. Not so. But I do, admittedly, possess a somewhat low regard of certain aspects of American culture, which still bears a strong imprint from Puritanical Voodoo with its black-and-white morality and apocalyptic eschatology. Very bad people (read: Satan and his minions) do unspeakable things to the innocent (read: the faithful). The moral? The Messiah is coming. (Look busy.)

This simplistic kind of morality also bore no resemblance to what I saw as a PI, and I wanted no part in continuing to propagate a beguiling (if wildly popular and thus potentially lucrative) delusion. I know all novelists lie. I just didn’t want to lie about that.

And so I have written four novels that deal with more morally and psychologically complex individuals whose lives are touched by crime: a marijuana smuggler who takes the fall for his crew and leaves prison dedicated to finding his hard-luck girlfriend; a cop who can’t shake the ghost of his brother who died pointlessly in Vietnam; an irascible musician who dies out of some mistaken jealous rage at the hands of a patsy arsonist; a bodyguard whose attempt to outrun his bent cop father’s legacy only lands him squarely back in its grip; an up-and-coming Latino musician obliged to make a pact with the devil to help his deported uncle emigrate back to the States. And, as anyone who’s read my work knows, I am particularly fond of the charming and expertly manipulative sociopath, a variety of creature with whom I’ve had more than my share of firsthand experience. And not just dating.

That said, I am venturing into PI territory with the book I am just beginning. (It will be my fifth; the fourth, Do They Know I’m Running?, comes out early in 2010.) I don’t want to spoil things, but Dan Abatangelo, the marijuana smuggler protagonist of The Devil’s Redhead, will appear as a stringer for a PI firm with connections to his sister’s law practice. I will return to Rio Mirada, the setting of my second novel, Done for a Dime, and deal with political corruption in both city hall and the public service unions.

That’s right, I am finally going to write the PI novel everyone has expected me to write. And I am really, really looking forward to it.

But I’d still rather be Duckman.

* * *

David and I spoke briefly at Bouchercon last year about our loyal, but aged friends, Tilly and Pebbles. During our conversation, we, two majorly tough guys, each produced our cellphones to share the photos we display as background images on the devices. The photos are of our beloved dogs. Two tough guys with soft spots for little dogs.

Since that time David’s longtime canine companion, Tilly, has passed away.

For Tilly:

The House Dog’s Grave

Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962)

I’ve changed my ways a little; I cannot now run with you

in the evenings along the shore, except in a kind of dream;

and you, if you dream a moment, you see me there.

So leave awhile the paw-marks on the front door

where I used to scratch to go out or in, and you’d soon open;

leave on the kitchen floor the marks of my drinking-pan.

I cannot lie by your fire as I used to do on the warm stone,

nor at the foot of your bed; no, all the nights through I lie alone.

But your kind thought has laid me less than six feet outside your window

where firelight so often plays, and where you sit to read

– and I fear often grieving for me- every night your lamplight lies on my

place.

You, man and woman, live so long, it is hard to think of you ever dying.

A little dog would get tired, living so long.

I hope that when you are lying under the ground like me

your lives will appear as good and joyful as mine.

No, dears, that’s too much hope:

You are not so well cared for as I have been.

And never have known the passionate undivided fidelities that I knew.

Your minds are perhaps too active, too many-sided…

But to me you were true.

You were never masters, but friends. I was your friend.

I loved you well, and was loved. Deep love endures

To the end and far past the end. If this is my end,

I am not lonely. I am not afraid. I am still yours.

0-Software-for-Writers/storybasebox.jpg)