In my previous blog, The Importance of Traffic Stops, I discussed some of the reasons why law enforcement conducts traffic stops and provided some real-life examples from my career. In this blog I am going to talk about the mechanics of traffic stops and the decision process an officer goes through before ever turning on the emergency lights.

Before ever conducting a traffic stop, an officer must be intimately familiar with their traffic codes, to the point of memorizing them. An officer has to know what is and is not a violation before pulling someone over and that information comes from the traffic law. Officers must also keep up with the ever-changing case law as it relates to traffic-related enforcement and searches. Beyond legal requirements, officers must know their beat and jurisdiction like the back of their hand. If a simple traffic violation becomes a pursuit, the officer must know where to direct other units, how to create a perimeter, and anticipate the offenders next move. Officers must also know where large parking lots are, where roads widen and narrow, and where people congregate. The last thing an officer wants to do is pull over a stolen car or dangerous felon in a school parking lot.

Once an officer finds either probable cause or reasonable suspicion to stop a vehicle, the officer must first decide if they want to take action. An officer has discretion on what to enforce and what not to enforce and officers always notice violations that they don’t take action on. For example, an officer assigned to DUII enforcement that notices a family driving through town that appears lost and failed to signal a turn is most likely not going to stop them. On the other hand, the driver that is traveling ten miles per hour under the posted speed limit and driving without headlights at night is guaranteed to meet the DUII officer very quickly.

As soon as the officer decides they are going to initiate a traffic stop, the officer has to decide whether they want to immediately stop the car, or watch it for a while. Sometimes watching a vehicle to gather additional evidence is advisable as long as it is not putting the general public in further harm. An officer may also need to overtake the vehicle and do so in a manner that the driver does not realize they are about to get pulled over. The element of surprise is very advantageous to the officer; the more time the driver has to think, the more time they may have to plan an assault against the officer. On occasion I have had people just pull over as soon as they saw me either turn around, or pull out of the area I was sitting. They knew they were guilty and they weren’t going to make me chase them down. I always appreciated that and was a little less worried about those individuals than the ones who immediately increased their speed as soon as they noticed me notice them.

The emergency lights have still not been activated yet as there are more decisions to make. The officer must determine where they want the car to stop. Obviously the officer has no control over this, but they will try to wait until the vehicle is in a safe place to conduct a traffic stop. This is generally not on the top of an overpass or in the middle of an “s” curve, but somewhere that provides the officer and violator plenty of room to pull over safely and be out of traffic. This is not always possible and sometimes violators will travel a long distance before they notice the police car behind them, especially with all the distractions like cell phones, iPods, loud stereos, and passengers.

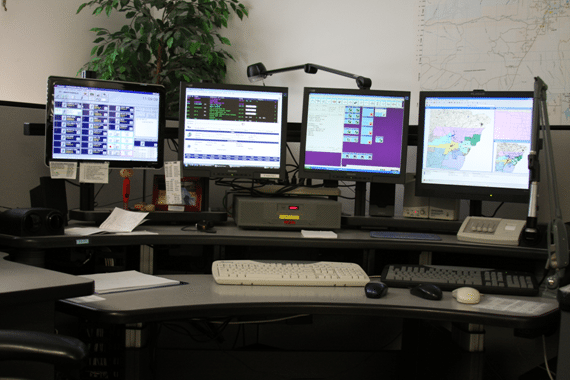

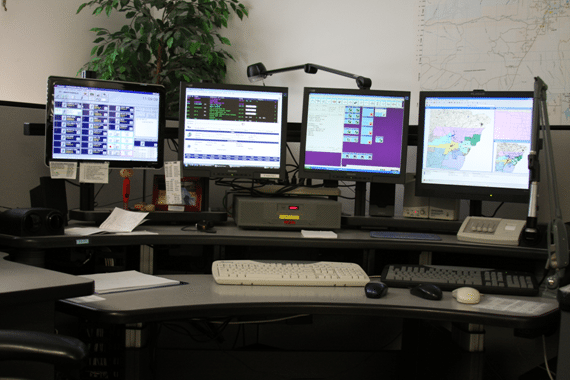

Now that the officer has decided to take enforcement action and is close enough to the vehicle to read the license plate, the officer must pre-plan where the traffic stop will occur and radio in the stop to the dispatch center. I always told dispatch where my stop was going to be before I ever turned on my lights. That way, if things went immediately bad, at least dispatch knew where I was generally. I knew some officers that would pull over a vehicle, make contact with the violator, and then notify dispatch they were on a stop. This is extremely poor officer safety skills; if anything happened to that officer before they radioed out on the stop who knows how long it would take to find them.

Typical dispatch center console

Each jurisdiction is a little different, but for me my radio transmission would be something like this:

Me: “519 traffic stop.” (519 was one of my radio identifiers. Radio ID’s or call signs could be another blog post all its own)

Dispatch: “519.”

Me: “519, Oregon Adam Baker Charles One Two Three, East Main and Mountain.” (This is the state the vehicle is registered to, license plate of the vehicle in phonetics, and the location and cross street of my stop).

Dispatch: “Copy 519.”

At this point, dispatch would be running the license plate as fast as they could to see if there were any officer safety alerts about the vehicle (stolen car, stolen plates, other alerts) and they would also run a check automatically on the registered owner of the vehicle since it is most likely the driver. No news was good news from dispatch on this check and dispatch is trained to leave the officer alone for the first few minutes of the stop. (Side note – If dispatch doesn’t hear anything from the officer within five minutes of the stop they begin to do status checks. If the officer doesn’t answer the status checks, backup officers are sent to check on the officer). If I heard dispatch calling me within one or two minutes, I knew something was wrong with the vehicle or registered owner. Sometimes this message wouldn’t get to me though until I already had the car pulled over.

Officer calling into dispatch on their mobile radio

As soon as I radioed in the plate and my location I was ready to turn on my emergency lights. I would activate all of the necessary switches and if at night, would turn on my takedown lights (forward facing white lights on lightbar) and my spotlight as the car was stopping. Notice I never mentioned the siren. Contrary to many shows and movies, an officer doesn’t turn on the siren right away and usually only if the vehicle is failing to yield to the officer. Proper lighting at night allows an officer to see into the vehicle better and blinds the vehicle occupants so they don’t know where the officer is standing.

Once the lights are activated, this becomes the most critical time in the stop. The reaction of the driver is completely unpredictable and the officer must be ready for anything. Will the driver speed up and the chase is on? Will they immediately slam on their brakes and stay in the middle of the road? Will they drive for the next two miles and not even notice the police car even with the siren on? Or, will they calmly pull over to the right and stop? I’ve had every one of these scenarios happen to me. The officer has to be prepared for anything. If the stop actually ends up far away from the original location, the officer should immediately notify dispatch of their updated location.

As the car begins pulling over and slowing down the officer should be getting ready to exit the patrol car as fast as possible. The driver’s seat of a patrol car is called the “coffin” during a traffic stop and no officer should ever sit in the driver’s seat during a stop. It was my practice to take off my seatbelt once we hit ten miles per hour and at five miles per hour I had my hand on the drivers door handle. As soon as we stopped I could position my car, put it in park, set the parking brake, hit the door unlock button and be outside the vehicle all in one smooth motion. If the driver jumped out and started shooting at me or charging me, I was immediately able to protect myself.

Now that the car is stopped things get more serious. At night, I would always pause and watch what is going on. Sometimes I would walk all the way around the trunk of my car and stand on the passenger side and just watch the occupants if I was worried about something. I also did this so I never crossed in front of my headlights or takedown lights, giving the vehicle occupants an idea of where I was. I have had everything from people jumping out of the car and running, drugs being thrown out windows, and people coming out of the car and physically fighting me. I also knew whether or not my offender was “well versed” in police procedure if as soon as the car stopped everyone inside had his or her hands up. If I felt uncomfortable about a traffic stop, I would request a backup unit on the radio.

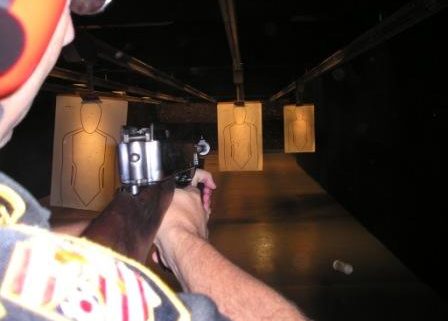

While I approached the vehicle, my hand was always on my weapon. I wore a triple-retention holster for my Glock model 22, meaning it took three steps to unholster the gun. As I walked up, I always released one of the safety mechanisms so I could draw faster, but it was still relatively safe from getting taken in the event I got into a physical fight with an occupant. My favorite way to approach a vehicle was from the passenger side. In the daytime the vehicle occupants can watch the officer approach the car which is much more dangerous. At night I would try and sneak up on the driver and could usually watch the driver for a few seconds from the passenger window until I knocked on it to get their attention. On several occasions I saw people hiding drugs, guns, and other evidence while they were waiting for me to get up to the vehicle, not knowing I was already there. I also liked mixing it up a bit. I would first approach the passenger side, get their license, registration, and insurance; then after I checked those with dispatch back at my car, I would walk up to the driver’s side. This time I could get a better look at their eyes and could smell them and the vehicle better for things like alcohol and drugs.

This is the style of holster I wore – a level III retention for the Glock with the tactical light attached.

If I returned to my patrol car for any reason during the stop I would stand behind my passenger door to give me some cover. This way I could watch the vehicle while checking for warrants on the vehicle’s occupants and/or while I was writing a citation or waiting for a cover unit. Another option is to get away from the patrol car and take cover behind an object nearby, such as a tree or other barrier.

At the conclusion of my stop I would provide the driver with their information back and either issue the citation or give them a warning. It was always my rule to give a ticket or a lecture, but never both and I always treated offenders with complete dignity and respect. When I walked back to my vehicle after releasing the driver, I would always look over my shoulder while walking back to my car in case the driver or other occupants tried to get out. I would get back in my car and wait for the driver to get back on the road and never drive past the driver, especially if they were extremely upset. This way the driver could not shoot at me while I drove past them. I would advise dispatch that I was clear of the traffic stop and go on my way.

The above scenario is a typical “unknown-risk” traffic stop. A high-risk traffic stop has a few more moving parts and requires some additional tactical planning.

A high-risk traffic stop is used for a variety of reasons, most of which involve the driver being suspected of committing a felony. High-risk stops are most commonly used when stopping stolen vehicles, vehicles occupied by individuals who are wanted for committing a dangerous crime, or at the conclusion of a pursuit. High-risk stops should always be done by at least two officers and preferably with three or more.

When an officer determines they are going to initiate a high-risk traffic stop, the best practice is to follow the suspect vehicle until at least one or two more backup units are behind the first police vehicle. This may mean that the lead officer is following the suspect car as the other units are traveling code-3 (lights and siren) to catch up. The responding back-up officers will make sure to turn off all lights and siren way before the suspect vehicle could see or hear them coming up behind.

The lead officer will announce where the stop is going to take place (again, hoping for the driver’s cooperation) and also let dispatch know they are conducting a high-risk (sometimes referred to as a felony) stop. High-risk stops should be made in large unpopulated areas if possible to minimize collateral damage if shooting takes place. When all of the units are ready, they will activate their lights. If personnel exist to do so, a unit will find a way to block traffic in front of the stop, but out of bullet range so bystanders aren’t driving through the stop.

The radio traffic would be similar to this:

Me: “519, units will be initiating a high-risk traffic stop at 8th and Lincoln, clear the channel.”

Dispatch: “Copy 519. All units, all units, 519 and units are out on a high-risk traffic stop at 8th and Lincoln, channel is emergency traffic only.”

Clearing the channel means that only those involved in the serious emergency can talk on the channel and other units not involved must go to a secondary channel for normal business.

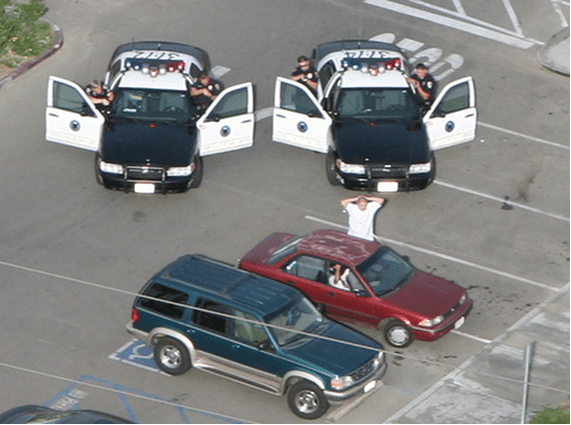

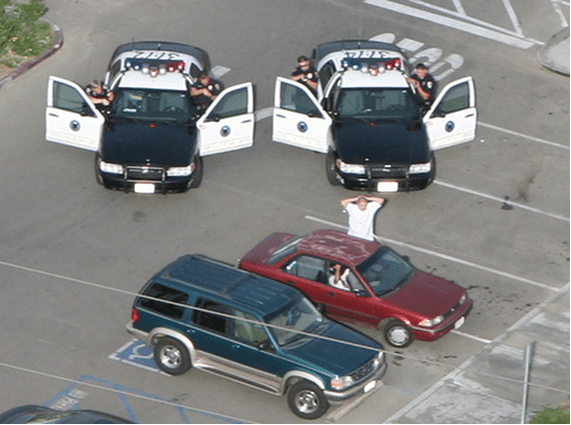

The units would have coordinated on the radio who was going to do what. For example, the lead officer will direct one unit to either come up next to the lead officer’s vehicle at the stop (called a fanning stop) or pull in behind the first car (called a stacked stop). Officers have certain duties and places to stand during a high-risk stop that is drilled into them during training.

Typical fanning approach to a traffic stop

All officers will have their guns drawn and pointed in a “low ready” position toward the vehicle. Some officer may have their handguns and some may have shotguns or rifles. Usually the lead officer will begin giving the vehicle verbal commands either by yelling or using a PA system. Typical commands including “This is the ABC police department, everyone put your hands up.” Commands would continue to have the driver turn off the car, give the driver instructions on what to do with the keys, and then bring each person out one-by-one. After the last know person is out of the car the officers will “challenge” the vehicle again, assuming that someone is hiding in the car. The officers will then advance on the vehicle and search it inside as well as in the trunk for any other suspects.

Hopefully these blogs have been useful and shown that a traffic stop is much more than just driving up behind a vehicle and turning on the emergency lights. Officers not only have to worry about the vehicle occupants, but also about other traffic. In 2011, eleven law enforcement officers were killed in the line of duty from being struck by a vehicle and 140 officers have lost their lives to this in the past ten years.

* * *

Josh Moulin

Josh has a long history of public service, beginning in 1993 as a Firefighter and EMT. After eight years of various assignments, Josh left the fire service with the rank of Lieutenant when he was hired as a police officer.

Josh spent the next eleven years in law enforcement working various assignments. Josh worked as a patrol officer, field training officer, arson investigator, detective, forensic computer examiner, sergeant, lieutenant, and task force commander.

The last seven years of Josh’s law enforcement career was spent as the commander of a regional, multi-jurisdictional, federal cyber crime task force. Josh oversaw cyber crime investigations and digital forensic examinations for over 50 local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. Under Josh’s leadership, the forensics lab was accredited by the American Society of Crime Lab Directors / Laboratory Accreditation Board (ASCLD/LAB) in 2009.

Josh has been recognized as a national expert in the field of digital evidence and cyber crime and frequently speaks across the nation on various topics. He has testified as an expert witness in digital forensics and cyber crime in both state and federal court on several occasions. He also holds a variety of digital forensic and law enforcement certifications, has an associate’s degree and graduated summa cum laude with his bachelor’s degree.

In 2012 Josh left law enforcement to pursue a full-time career in cyber security, incident response, and forensics supporting a federal agency. Josh now leads the Monitor and Control Team of a Cyber Security Office and his team is responsible for daily cyber security operations such as; incident response, digital forensics, network monitoring, log review, network perimeter protection, and firewall management.