Lieutenant David Swords (ret.) is a thirty year veteran of the Springfield, Ohio Police Department. Nearly half of Lt. Swords’ police career was spent as an investigator, working on cases ranging from simple vandalisms to armed robberies and murders.

The Interrogation

Body language

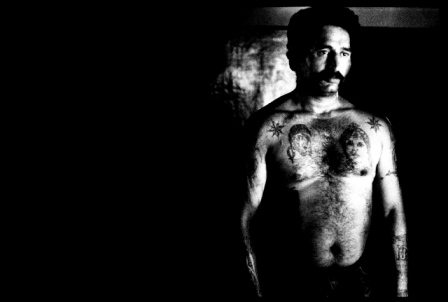

One of the primary things an interrogator must do is watch the suspect. A veteran once told me, “You’ll learn more by watching a man’s eyes then by listening to his words.”

Kinesics is the study of body language in communication, including eye movements. One field of study concerning eye movements went so far as to suggest one could determine truthfulness or deception by watching which direction the eyes moved in response to questioning. I’m not sure of the exact information, but examples of what I mean might be looking down and to the left could indicate deception, while looking up and to the right might show thoughtful consideration of the questions. If your story takes place in recent years, you can probably find detailed information on this system.

In any event, eye contact is crucial during an interrogation and has been known and used by officers probably since Marshall Dillon questioned Black Bart. Think about questioning little children when the cookie jar gets broken. Where are their eyes when you ask what happened? Looking straight at their shoes, of course. It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to look someone in the eye and lie to them. Even if the eyes flick away for just a split second, it’s there. The deception. You can see it in the eyes.

The movement of the eyes is not the only thing a detective watches for in an interrogation. All physical mannerisms can betray persons as they are being questioned. You can find these in books or on the Internet, so I won’t go into great detail on each, but I’d like to point out some of the more common movements and what they might mean.

– The arms folded across the chest. Arms across the chest can indicate a closed mind or defiance.

– One I always loved to watch for was an almost imperceptible drop of the shoulders, sometimes accompanied with a sigh. This showed resignation and often indicated the suspect was about to give up his resistance.

– Head nodding or shaking. An officer knows he is close when the suspect begins to, very slightly, nod or shake his head in agreement with what the detective is saying. Another sign that you are close to a confession.

– Grooming, or repeating a question. Both are common stalling tactics. By grooming, I mean the suspect will pick at lint or brush something off their shoulder.

And as for repeating, we’ve all heard it and done it. “Where were you last night?” “Where was I last night?” They’re stalling, thinking quickly for an answer, when the real one might put them in jail.

All of the above, and scores of other bits of body language, can mean something. A detective needs to watch closely to know when to “make his move.”

What do I mean by make his move?

There comes a point when a person is close to confessing and needs a little nudge to get him to cross that line. One thing an officer might want to do is slide in closer to the suspect. It invades the man’s personal space. It’s a way to say to the suspect, ‘I’m in your space and in your head, we know the truth, it’s time to say it.’

At this point in time, you’re not asking the suspect what happened, you’re telling him, and you don’t let him disagree. You’re probably also speaking very softly, not yelling or in the guy’s face, so to speak. “You took that TV last night, Bob.” And when he shakes his head no. “Yes you did, we all know you did. You need to tell me about it.”

Notice the detective said “took” and not “steal.” It’s important to try to express the accusation in soft words, not harsh ones. It’s easier to admit “taking” something and not “stealing” it. Once the suspect crosses that magic line and kicks into the crime, you can clear up details.

He didn’t break in, he went in. He didn’t steal, he took. He didn’t rape, he had sex with. It might seem trivial, but the differences can mean success or failure.

An important point to add is the use of accusation to get a response and see if you’re on the right trail. An officer will often make an accusation just to see how the suspect reacts. An innocent person will react with indignation when an outright accusation is made, while the guilty party will still deny it, but with much less vigor.

“You had sex with that with that young girl,” can be answered with eyes dropped to the floor and a rather calm, “No, no, I did not.” Or it may be answered with an emphatic, “I DID NOT!” while the suspect looks straight in your eyes. You can see the difference.

Officers may also use an over-accusation to gain information. I once had a detective who worked juvenile tell me of a man he was questioning on an accusation that the man had stopped two schoolgirls and offered them fifty cents to pull up their dresses and show him their underwear. The man denied any wrongdoing until the detective said that he had been told the man had given the girls five dollars each, to which he replied, “I did not, I did not, I only gave ‘em fifty cents.” Not the brightest bulb in the chandelier, but the officer had his confession.

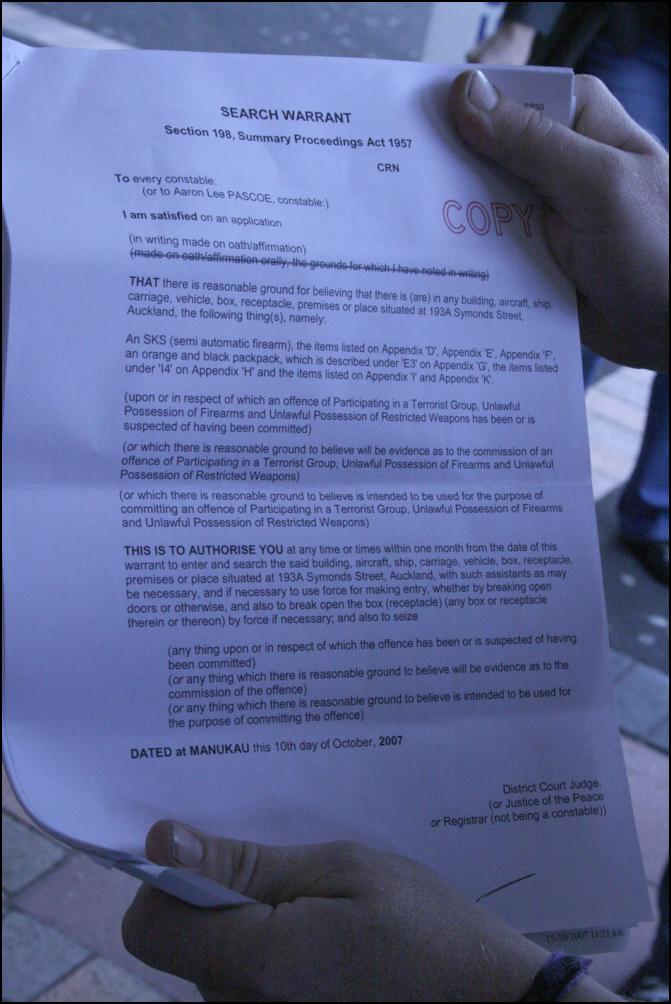

Street officers can use a form of accusation just to find out a person’s name. An officer who holds a warrant for Joe Smith won’t walk up to someone he believes to be the suspect and ask, “Are you Joe Smith?” Rather, he will ask, “Are you Bill Brown?” When this is denied, he’ll say, “Oh, yes you are, you’re Bill Brown.” What he will often get is an indignant, “I am not, I’m Joe Smith!” And off to jail he goes.

Something else that can work wonders, especially when dealing with a homicide or violent crime, is to bring the victim into the room. Now, I don’t mean you send your partner to the morgue to drag in a corpse. But, you can bring in a personal item that belonged to the suspect, perhaps a piece of bloodstained clothing. Once it’s time to make your move, such an item can serve to bring the victim into the room to point the finger of accusation at the suspect. Hand it to him, allow him to touch it. You can imagine the effect it can have.

The Secret to writing about interrogations

There really is a secret to writing about interrogations and I am now going to reveal it to. Are you ready? Here it is. The secret to writing about interrogations is that there is no secret. Believe me, it is not rocket science. You have most of the tools you need, and that is your own experience in talking with people. All you need to do is close your eyes, imagine the scene, and put words to paper to describe what happens.

Take a tip from Stephen King in his book “On Writing – A Memoir of the Craft.”

“When you step away from the ‘write what you know’ rule, research becomes inevitable, and it can add a lot to your story. Just don’t end up with the tail wagging the dog; remember that you are writing a novel, not a research paper. The story always come first.”

You’re doing research now, by reading this brilliant blog. (Was that a little too obvious?)

You won’t use everything in this blog, just enough to add a little legitimacy to your story.

And remember, it is not always in the details – it’s in the story.